Episode 05: Market-Rate Development and Neighborhood Rents with Evan Mast

Episode Summary: We’ve known for many years that building more homes helps keep prices in check at the regional or metro area level, but what about the house down the street? When a new apartment building goes up nearby, does the “supply effect” of more homes lower rents, or does the “demand effect” send a signal to nearby property owners and potential residents that causes rents to go up? Evan Mast of the Upjohn Institute joins Mike and Shane to discuss two recent papers he’s worked on that help shed light on this important and controversial question.

- Asquith, B., Mast, E., & Reed, D. (2019). Supply shock versus demand shock: The local effects of new housing in low-income areas. Upjohn Institute WP, 19-316.

- Abstract: We study the local effects of new market-rate housing in low-income areas using microdata on large apartment buildings, rents, and migration. New buildings decrease nearby rents by 5 to 7 percent relative to locations slightly farther away or developed later, and they increase in-migration from low-income areas. Results are driven by a large supply effect—we show that new buildings absorb many high-income households—that overwhelms any offsetting endogenous amenity effect. The latter may be small because most new buildings go into already-changing areas. Contrary to common concerns, new buildings slow local rent increases rather than initiate or accelerate them.

- Mast, E. (2019). The effect of new market-rate housing construction on the low-income housing market. Upjohn Institute WP, 19-307.

- Abstract: Increasing supply is frequently proposed as a solution to rising housing costs. However, there is little evidence on how new market-rate construction—which is typically expensive—affects the market for lower quality housing in the short run. I begin by using address history data to identify 52,000 residents of new multifamily buildings in large cities, their previous address, the current residents of those addresses, and so on. This sequence quickly adds lower-income neighborhoods, suggesting that strong migratory connections link the low-income market to new construction. Next, I combine the address histories with a simulation model to estimate that building 100 new market-rate units leads 45-70 and 17-39 people to move out of below-median and bottom-quintile income tracts, respectively, with almost all of the effect occurring within five years. This suggests that new construction reduces demand and loosens the housing market in low- and middle-income areas, even in the short run.

- Li, X. (2019). Do new housing units in your backyard raise your rents. Working paper.

- Guerrieri, V., Hartley, D., & Hurst, E. (2013). Endogenous gentrification and housing price dynamics. Journal of Public Economics, 100, 45-60.

- Phillips, S., Manville, M., & Lens, M. (2021). Research Roundup: The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

- Diamond, R., McQuade, T., & Qian, F. (2019). The effects of rent control expansion on tenants, landlords, and inequality: Evidence from San Francisco. American Economic Review, 109(9), 3365-94.

- Liu, L., McManus, D. A., & Yannopoulos, E. (2020). Geographic and Temporal Variation in Housing Filtering Rates. Available at SSRN.

- “Opportunities and Obstacles for Rental Housing Registries,” Jan. 20 Lewis Center event with Assembly member Buffy Wicks and Catherine Bracy. https://youtu.be/vaDTWHxk-I8

ASQUITH, MAST, REED ABSTRACT:

- “We study the local effects of new market-rate housing in low-income areas using microdata on large apartment buildings, rents, and migration. New buildings decrease nearby rents by 5 to 7 percent relative to locations slightly farther away or developed later, and they increase in-migration from low-income areas. Results are driven by a large supply effect—we show that new buildings absorb many high-income households—that overwhelms any offsetting endogenous amenity effect. The latter may be small because most new buildings go into already-changing areas. Contrary to common concerns, new buildings slow local rent increases rather than initiate or accelerate them.”

- Sample: start with 1,483 buildings in 11 central cities, remove income-restricted and senior housing, as well as buildings with over 25% college students. Also remove all buildings under 50 units and condo buildings, focusing on much more numerous rental buildings. Restrict to projects in census tracts with median household income below the CBSA median. Only buildings with no other new developments within 250 meters (i.e., where new buildings may represent a larger shock). 92 buildings are in the final sample.

- “Causal identification in this setting is challenging because developers select the locations of new buildings based in part on unobserved local characteristics and trends. In addition, the size and shape of a new building’s amenity or reputation effects is unknown, making it difficult to know where they may shrink or reverse the negative effect of added supply. We attempt to overcome these challenges by leveraging our unique data to construct three related empirical strategies. The first is a difference-in-differences specification that compares the area very close to a new building to the area slightly farther away (our “near-far” specification) … The second exercise is a difference-in-differences that compares listings near buildings completed in 2015 and 2016 to listings near buildings completed in 2019, after the conclusion of our sample (our “near-near” specification) … Finally, we combine both sources of variation into a triple-difference specification that effectively compares the near-far difference around 2015–2016 buildings to the near-far difference around 2019 buildings.”

- “In our second set of results, we study the effect on in-migration using individual address histories from Infutor Data Solutions. In-migration speaks directly to the policy debate on neighborhood change, allows us to study cheaper segments of the market that may be underrepresented in the Zillow data, and is the primary channel through which neighborhoods change. In our near-near specification, we find that new construction decreases the average origin neighborhood income of in-migrants to the nearby area by about 2 percent. It also increases the share of in-migrants who are from very low-income neighborhoods by about three percentage points, suggesting that new buildings reduce costs in lower segments of the housing market, not just in the high-end units that are the most direct competitors of new buildings. Results are similar in the triple-difference specification and null in the near-far specification.”

- “Our exploration of where new market-rate rental apartments are built provides one explanation for why endogenous amenity or reputation effects may be small: new construction typically occurs after a neighborhood has already begun to change. Although we restrict to neighborhoods that are relatively low-income, those that receive new buildings are relatively high-education and experienced more income and education growth over the previous decade compared to neighborhoods that did not receive any new buildings. This suggests that rather than catalyzing demographic change in previously stable neighborhoods, new market-rate construction in low-income areas tends to follow neighborhood change, or gentrification.”

- “However, there are a few reasons for caution. First, our findings are specific to the large market-rate apartments and strong market cities that we study, and effects could differ for other types of housing or other areas if amenity effects depend on local context. Second, we are only able to follow outcomes for three years after building completion, though we provide evidence that longer-run effects are likely similar to our estimates. Finally, the actual implementation of reforms that increase housing supply requires changing complicated zoning and land-use regulations. Policymakers should keep in mind that the particulars of those changes could affect where housing is built—for example, in vacant lots or through demolition of existing affordable housing.”

- Working papers with similar findings:

MAST ABSTRACT:

- “Increasing supply is frequently proposed as a solution to rising housing costs. However, there is little evidence on how new market-rate construction—which is typically expensive—affects the market for lower quality housing in the short run. I begin by using address history data to identify 52,000 residents of new multifamily buildings in large cities, their previous address, the current residents of those addresses, and so on. This sequence quickly adds lower-income neighborhoods, suggesting that strong migratory connections link the low-income market to new construction. Next, I combine the address histories with a simulation model to estimate that building 100 new market-rate units leads 45-70 and 17-39 people to move out of below-median and bottom-quintile income tracts, respectively, with almost all of the effect occurring within five years. This suggests that new construction reduces demand and loosens the housing market in low and middle-income areas, even in the short run.”

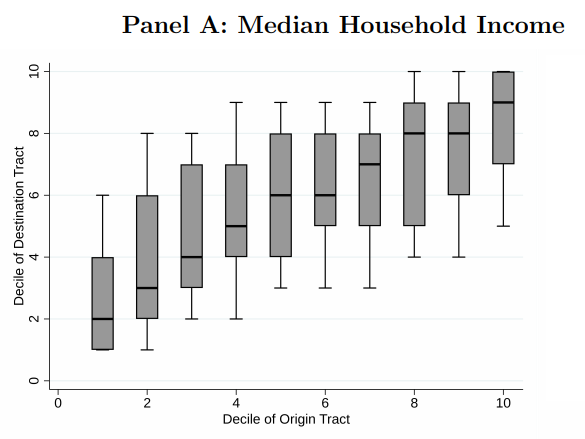

- “I first broadly consider migratory connections between neighborhoods in 12 major metropolitan areas (CBSAs) and find strong connectivity between census tracts with slightly different characteristics. Individuals originating in, say, the fifth income decile frequently move to the fourth or seventh decile, but rarely the tenth or first. This pattern implies that distinct submarkets exist, but that even quite different areas are connected by a short series of common moves.”

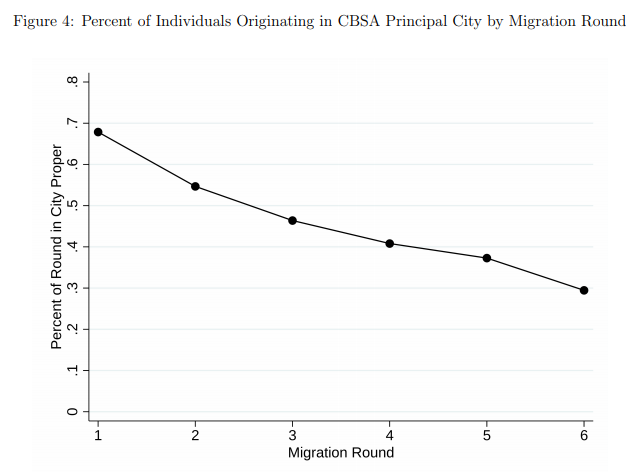

- “I identify 686 large new market-rate multifamily buildings in central cities and track 52,000 of their current residents to their previous building of residence. I then find the tenants currently living in those buildings and track them to their previous residence, iterating for six rounds and, in order to focus on local connectivity, keeping only within-CBSA moves in each round. About 20 percent of new building residents moved in from tracts with below CBSA-median income, and that proportion rises steadily to 40 percent in round six.”

- “I define the number of “equivalent units” a new unit produces in a submarket—say, below-median income tracts—as the probability that its migration chain reaches such an area before ending. The intuition behind this metric is simple: inducing a household to leave a submarket is similar to building a new (depreciated) unit in that submarket.”

- “In my baseline specification, 100 new market-rate units create 70 equivalent units in below-median income tracts and 39 in bottom-quintile income areas. In my most conservative specification, in which chains end with a much higher probability, I find 45 and 17 equivalent units in below-median and bottom-quintile income areas, respectively.”

- “However, a caveat is that I do not estimate price effects. Because the private market will not provide housing at below marginal cost, market-based strategies may not lower prices in neighborhoods with already very low prices. Alternative policies that either lower the cost of provision or subsidize incomes are likely necessary to improve affordability in such areas. Another limitation is that I study regional effects, and new buildings could have different effects on their neighborhood, where they may change amenities or demographic composition.”

Shane Phillips 0:10

Hello, and welcome back to UCLA Housing Voice podcast. We are on episode number five. I'm Shane Phillips housing initiative project manager for the UCLA Lewis center, joined by co host, Dr. Mike Lens, Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy at UCLA, and Associate Faculty Director of the Lewis center. The Housing Voice podcast is about bringing timely and important housing research to a broader audience. We're here to talk to the researchers themselves, about what they've learned what it means, and how we might apply their findings to make our cities more affordable and more equitable. If you haven't already subscribed to the podcast, please do. You could find us just about anywhere, and be sure to give us a rating if you'd like to show. I'm not gonna say rate, review and share just rate. That's my one ask if you today, maybe next week, it'll be review. I'm trying a new strategy here. Just ask one small thing at a time. This time, it's a rating, so simple, we appreciate you. With all that out of the way, let's just get started.

Today we're joined by Dr. Evan Mast. Evan got his PhD in economics from Stanford and currently works as a staff economist for the Upjohn Institute for employment research, headquartered in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Evan has worked on a couple of really fascinating papers that fit into a fast-growing body of research on how market-rate housing development impacts the housing market at a neighborhood level. So thank you very much for joining us to talk about your work today Evan.

Evan Mast 1:44

Yeah, thanks for having me on. This is fun to get to see you guys. And you know, fill some of that void that we are missing from not having conferences.

Shane Phillips 1:53

Yeah, and we've got, as always, Dr. Mike lens with us another connection to the Midwest here. Hi, Mike.

Michael Lens 2:00

Hello, Shane, and Evan and listeners everywhere.

Shane Phillips 2:04

So to start off, Evan, can you tell us a little bit about your background? I'll admit, you know, I wasn't familiar with Upjohn Institute before reading your work. So I'm curious how an employment research institute ended up working on housing.

Evan Mast 2:17

Yeah, so I'm an urban economist. So I do some stuff besides housing, I'm kind of interested in all sorts of things about, you know, cities and how they grow and decline, how do they attract businesses how do taxes play into this, how does municipal governance, you know, affect various things. And the Upjohn Institute does a lot of work on regional economics and local policy. That's sort of something that it focuses on, in addition to employment, the thought is, "oh, you know, we're out in Michigan so let's try to do state and local stuff, right, and not compete with DC on federal stuff". So yeah, I think I fit in pretty well to that wing of the Institute. But I'm not doing unemployment insurance, or kind of what you might think, from the name of the organization.

Shane Phillips 2:59

Gotcha. And before we talk about your papers, I'm going to take my own prerogative here and give a little background and just start. So these papers are about market rate housing development, what the impacts are at the neighborhood level. So we should start with just what we mean by market-rate housing for anyone that's it's not already clear for. When we talk about market rate housing, we're talking about housing that is rented or sold at whatever price people are willing to pay. So that's in contrast to income-restricted housing, what we sometimes call affordable housing, that sets a ceiling on how much rent can be charged, and how much a household can earn to be eligible to live in it. And as a general rule, market-rate housing is built for profit and without subsidies. And affordable housing is built by nonprofits with public subsidies. And because the cost of land and construction is very high in places like LA, both market rate and affordable housing are really expensive to build. But because market-rate housing doesn't receive any subsidies, it has to charge quite a bit to turn a profit. And we have a lot of very strong evidence based on decades of research that building housing helps keep prices under control, at a metropolitan level, at a regional level, even if that housing is relatively expensive market-rate housing. If there's a lot of demand to live in the metro area, and we don't build enough housing there, we end up with a growing number of people and dollars chasing too few homes, and the people willing to pay the most are the ones who get to stay; prices rise as a result. Before I continue, because I have even more to say unfortunately, Evan or Mike, anything you want to add to what I said so far.

Evan Mast 4:37

Sounds like a good summary to me. Cool.

Michael Lens 4:39

Yeah. I mean, housing markets are regional right? And so it's fine and great that we have a lot of evidence that, you know, building more at that regional scale has positive effects on affordability, but we also don't build regionally necessarily. We don't administer zoning and other mechanisms to build on a regional scale. And like these decisions are all are often very hyper local. Right? And so it's really important that we know this, this neighborhood standard,

Shane Phillips 5:14

And that's a good lead in. So what remains an open question in the research is how market rate development affects housing prices at the neighborhood level. So with, you know, down the street, across the block, whatever, there's a concern, and I think this is a valid concern, that if you build a new market-rate building in a neighborhood, especially a poor or working class neighborhood, that you may be doing something positive for regional or metro area, affordability, but actually harming in some way, that local community. You're adding supply, and that's helping relieve the pressure in the overall market. But you're also changing the community in a way that might make it more desirable and cause more people to want to live there, or signal to the existing landlords that this is an up-and-coming neighborhood, and you know, as a result, they might want to raise their rents. There's a supply effect that lowers prices by increasing supply and a demand effect or amenity effect that raises prices by making the area, the nearby area, more desirable. And the question is, which of these two effects is stronger at that neighborhood level? Answering that question empirically requires data on the rents of individual units and buildings, and until recently, that wasn't really available to us. But new data sources and the use of things like Craigslist ads and Zillow data have made that possible, and that brings us to Evans work. So as I mentioned, Evan, you actually have two papers that we're talking about here today, one authored just by you and the other co authored with Brian Asquith, and Devin Read. The latter of those two papers is titled 'Supply Shock versus Demand Shock: The Local Effects of New Housing in Low-Income Areas'. And I'd like to start with that one because as the name suggests, it deals directly with the supply effect versus demand effect question. So can you just start off by giving us an overview of what you and your co-authors studied, and what results you found , starting maybe with the impacts on rents?

Evan Mast 7:15

Yep. Yeah, so that was a really good description of the setting and kind of the question that we're trying to get at. So our goal was to test this idea, empirically see, you know, do big new apartment buildings in low-income areas, actually kind of counter-intuitively raise rents nearby or is it the opposite story, we see, "Okay, well, we added supply, and now rents are gonna go down". So what we did is we got together a sample of big apartment buildings, which are over 50 units, ao that's big, but not huge, you know, that could be like a four or five-storey building in big cities. So I think there are 13 cities in our sample, you should think of kind of roughly the 13 biggest in the US. And our results suggest that rents do not seem to go up faster, near these new buildings. So that doesn't mean the new buildings make rents nearby actually go down, like from $2,000 to $1900, it means that rents nearby seem to go up more slowly, than in a comparison group, or a similar set of apartment buildings, right? So to do that, we kind of take this like treatment control approach, where we say, okay, we're going to compare the area within a couple blocks of the new building, to some areas that seem like they're similar and where apartments should be, you know, following similar rent trajectories. So the two kind of control groups or comparable areas that we use, one, are apartments that are maybe like a five to 10-minute block from the new building, so slightly further away than the treatment group that we think is most effective. In the other group, our apartments near sites that were later developed into big new apartment buildings. Okay, so the idea is that these are going to be similar to the area near the new buildings, because look, ones in the same neighborhood, the other one was apparently similar enough that it eventually got a similar type of building. And when we do this comparison, at the end of the day, we find that the rents in our treatment group are about five to 7%, lower than the rents of those control groups. So it seems like, yeah, these buildings actually do lower the rents nearby. It's not this counter intuitive story, at least on average.

Shane Phillips 9:34

Right, right. And you note that compared to neighborhoods without a new development, the neighborhoods where market rate construction occurred, generally experienced faster growth in the college-educated share of the population and incomes prior to the project coming in. Can you talk about how you interpret those findings? I feel like that's a really important part of this actually.

Evan Mast 9:58

Yeah. I mean, probably the simplest way to say it is that, you know, these new buildings are following gentrification, they're not leading. And I mean, I think for one, that's, that explains part of our findings, these buildings are going into areas that are already changing. So this marginal change of adding whatever it might be 80 new high-income people isn't such a huge deal that it kind of changes the neighborhood's position, and, you know, in the metropolitan area hierarchy or really changes the businesses that are looking to locate there. I mean, I also think this makes sense, we're talking about, you know, pretty big buildings that, you know, take some capital to get off the ground, that requires some time to get planned and approved, and also, you know, the developer has to be able to get high enough rents to actually cover the cost of construction. So they're going to need an area where there's some indication that they can get rents like that.

Shane Phillips 10:53

Yeah.

Evan Mast 10:53

So yeah, I guess I think that this is sort of an intuitive part of the paper. And I also think that it highlights that we're studying one type of building in this paper, it's, you know, big new rental apartment buildings. And I think that's a reasonable thing to look at because this is where the issue comes to a head a lot of the time, it's like you got to a community meeting or reading the local newspaper, and a lot of the time, it's the type of building that people have in mind when they're pushing for upzoning or transferring to development or something like that. But you know, we do want to know that maybe it's a different story for a small-scale renovation, or if you put up a duplex, you know, that's not what we study.

Michael Lens 11:31

Yeah, yeah. This is really interesting. I think like, there's a couple things that that we're hitting on here. I think one is this fact that people see cranes, and they see big buildings. And somewhat simultaneously, they hear about their rent going up, right. And so there's this kind of temporal causal chain, that we're really trying to understand, like whether we really have this right, or whether people generally have this right or wrong, you know, is it the crane that really has anything to do it? Is it the big building that has anything to do with it or is the big building, of course, a response to these rising rents or the hope of rising rents if you're a developer? And then the other maybe a more pointed question for you, Evan, which, you know, I know, like, the methodological challenges in knowing this are huge. And I don't think you can fully speak to this but you're very smart on this issue, like, do you think we probably have like, both a supply effect from a building like this, and a potential demand effect from a building like this, you know, and that one way to interpret your findings is that this supply effect, which should reduce prices, is overcoming this demand effect that people think will increase prices, because this new building provides something to this neighborhood, in terms of new residents, a signal for new demand. Do you have any any thoughts on like that comparison?

Evan Mast 13:09

Yeah, I think it is a really good question if these positive amenity effects actually exist - is there actually kind of this push from the new buildings like oh, there's, you know, now there's going to be a grocery store, there's going to be whatever type of restaurant, the only direct evidence on this I know, is from Shouty Lee's paper on New York, and she finds something about more, maybe restaurant permits, it might even be like sidewalk cafe permits, I don't know what she was able to access but some measure of that does go up near new building. So she finds some evidence of an amenity effect. I can tell you that when people want to push back on this paper, a lot of times what they'll tell me is "Oh, your negative effect is because this building has negative amenities and people don't like it". Like it's interesting that like, sort of the one thing we could say about these big buildings, is that like they, they excite people's emotions, like one way or the other about them.

Michael Lens 14:07

Yes, yeah,

Shane Phillips 14:08

They feel strongly.

Evan Mast 14:09

Yeah, and to some extent, I don't know, I guess if there were, you know, a lot of rich people hankering to move to the area near a big new building, you might expect to see more excitement about this type of building when it's proposed in a high-income area. So all that's to say is I agree it's an empirical question, and I'd be interested to hear my research on that particular angle.

Shane Phillips 14:32

There's also, correct me if I'm if this is not really related, but Rebecca Diamond's paper where she looked I think at affordable housing specifically and found actually that prices near those developments went up. Is that am I remembering that general finding correctly or is there more to it?

Evan Mast 14:50

There's a little bit more to it. So she finds that when you put a low-income or light-tech building into a low income neighborhood, that tends to increase rent prices nearby, whereas you have the opposite effect in a high income area.

Shane Phillips 15:05

Gotcha.

Michael Lens 15:07

Interesting. Since since we've now brought up Shouty Lee, this is this the second NYU Furman Center graduate that we've discussed in addition to Devin Reed, and I need to note or give a shout-out to Devin, he's fast becoming the best housing researcher that graduated from Macalester College and NYU with a public administration PhD, overtaking me. And maybe there's others that I don't know about but good job Devin.

Shane Phillips 15:39

There's one other element of this paper that I think... well, there's several but one that we haven't actually talked about but it's in the title, is that you're looking at low-income areas. Can you tell us a little bit more about that aspect of this just how you're specifically looking at the effects in these communities?

Evan Mast 15:55

Yeah, so I think one, I don't know if I still have this weakness but three years ago, when I was coming up with these papers, I think it was sort of a weakness that I was really like, directly responding to the public debate. And I was like, Okay, this debate is about low-income areas, that's what I want to write about.

Shane Phillips 16:14

I share that weakness that's what I do.

Evan Mast 16:17

Right so that's why I started off working on it. I do think that this amenity mechanism is more plausible in low-income areas than high-income areas, because you can just sort of see this argument like, "oh, this purchasing power comes in, there's just more gross income in the neighborhood, and now, like, someone's gonna set up a business that can take advantage of that income. And that's going to be the snowball effect". So that's why I decided to focus on that. I mean, I think that a really interesting thing to do, and I don't know how to do it, would be to identify really precisely, like the types of places where you would expect a new building to actually raise rents, I don't think it would actually correspond exactly to low-income areas, I think it would have a lot to do with like, buildings that are somehow kind of changing like the physical form of a city. Like imagine there's a railway via docked between, you know, a wealthy neighborhood and a working-class neighborhood. And like some new buildings coming along that, and kind of like span that divide and now like, you breach the duct and you can bleed over into this new area, like that stuff sounds even more plausible to me, than this idea of just increased purchasing power. I don't know exactly how to get at that in a systematic way. I can point to things where I think it's happened, but I don't know how to do it in general.

Shane Phillips 17:42

Yeah.

Michael Lens 17:42

Yeah. I mean, that reminds me of some work, that Dan Hartley and some others were involved in where, you know, they really find strong evidence that your most gentrifiable or gentrifying neighborhoods are really most likely to be next to neighborhoods of high-income or more established neighborhood. So like, I mean, maybe that's kind of what you're talking about, right, where these border, you know, once were borders whether they were, you know, cultural, social, or physical, and, you know, the forces of change kind of often bleed, or sometimes, and perhaps even bleed over or across those borders. And certainly, in unpredictable ways, ofcourse, which is what makes so much of this policy so hard.

Shane Phillips 18:30

Totally agree. And to get into more critique here just to like, poke at things as much as we can, the Zillow data, in any data you pick for this kind of thing. I think there are questions with it. You use Zillow listings to determine the rents of nearby buildings. And I think that Zillow, from what I understand can be sort of skewed somewhat toward the higher end of the market so you're not necessarily capturing all of the housing units. How confident or how do you know that what you found here, based on the data that was available to you is really representative?

Evan Mast 19:05

Yeah, so I I agree, I think this is a general problem with rents data, I think that we need and maybe it's just, you know, you need the government to come in and run some kind of survey that gives you a better measure of rents. But I think like a really reliable granular source of rents would be a really helpful thing for the literature to have...

Shane Phillips 19:26

For the listeners, the UCLA Lewis center recently hosted an event on rental housing registries featuring Assembly member, Buffy Wicks, and Catherine Bracy of the tech equity collaborative. We'll make sure to put that in the show notes but that would be one way to really universally capture rents in a community. Go on, Evan.

Evan Mast 19:46

Yeah, that sounds great. I just learned we have a similar thing in Kalamazoo. You've got registered landlords, and I don't know if the city collects rents, but they could.

Shane Phillips 19:53

Yeah, yeah.

Evan Mast 19:54

So anyways, to actually get to your question, I think like the Zillow rent probably does skew a little bit higher. I don't think it's like divorced from the average in the neighborhood. Hmm, we do a little more to like show formally in some revisions that we're doing to the paper. So hopefully you'll be able to see that soon. But I want to say it's numbers, I don't want to give you anything off the top of my head. But I guess, a way to put it is like the mean in the Zillow data is probably not going to be that far from the mean, and the overall data. Is there a segment that's just not showing up in the Zillow data, maybe. And that's why we kind of bring in some migration data and try to bring in, you know, an alternative way to measure what the effects on that part of the market might be.

Shane Phillips 20:40

Yeah, and that is another good transition, because you did look at migration. And I think this is a really useful complement to the other findings in the paper. So what you found was that, in addition to these rent effects, where new development occur, the people who moved within 250 metres of the new building into some older existing housing, they came from slightly lower income neighborhoods than the people who moved into homes 250 to 600 meters away, so that control area. And so this seems to support the idea that the new developments are lowering nearby rents. So it's complimentary in that sense. And the reason I think is the people moving into those nearby buildings are coming from lower-income neighborhoods. So it just kind of naturally follows, am I understanding that aspect of this correctly?

Evan Mast 21:30

Yep. Yep, that was the idea of it. One thing was just to use another measure, use another data source to see if something's changing. And the other benefit to the migration data, is that we can sort of directly access the cheaper segment of the market.

Shane Phillips 21:46

What do you mean by that?

Evan Mast 21:46

So we can look at how many people move into the nearby area from like a really low-income neighborhood.

Shane Phillips 21:53

Hmm.

Evan Mast 21:54

And that tells us something, I need to get into the weeds, we can't do that with our rent data, because we don't observe the same unit over time. So we can't identify what is like, an initially cheap apartment. But with the migration data, we can do it because we can say, "okay, you moved in from a census tract with median income below half of the average in the metropolitan area". And that's where we find some increases in the number of people moving in from those areas, and that's why we say like, "we think this is probably lowering rents, you know, throughout the market, not just at the top".

Shane Phillips 22:29

Yeah, if you had found that people were moving actually from higher income neighborhoods into the nearest area around these buildings, that would be sort of contradictory to your rent findings. You know, it wouldn't invalidate them but it would cause you to question them a little bit more probably.

Evan Mast 22:44

Yeah, yep, definitely.

Shane Phillips 22:46

And so these results can lead us into your solo working paper, which is titled 'The Effect of New Market-Rate Housing Construction on the Low-income Housing Market', which sounds very similar. It focuses more narrowly on on migration. And I think it helps explain why development can lower rents at a higher level, say for the entire city, or metro area. And it centers around something that you call the migration chain, which I found really, really interesting. Can you explain what that is, and what it reveals in your research? I've tried to write about this multiple times. And putting it in writing clearly is very challenging. So I think having it verbally will be helpful.

Evan Mast 23:30

Yep, sure. So...

Michael Lens 23:32

Or twice as challenging.

Evan Mast 23:39

I've traded this paper around a few places. But it's funny that you mentioned the title, because I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to title these two papers differently so that people could tell them apart. Currently, I could have done better so...

Shane Phillips 23:54

Well, you've got the supply effect, and the demand effect one, so if that clarifies that much, right.

Evan Mast 23:59

So yeah, the idea of this paper is to show how new units can affect the broader housing market, even when those new units are really expensive. And the idea is that the sequence of moves or this migration, chane can make this link happen. So I think the easiest way to do it is to just like talk through an example with really like concrete numbers. And I tried to guess LA numbers, I'm not sure, these would be bad San Francisco numbers

Shane Phillips 24:27

We're gonna find out yeah.

Evan Mast 24:28

So alright, suppose you put up a new building, and a one bedroom goes for about 3000 a month?

Shane Phillips 24:33

Sure. All right. Those exist for sure. Yes.

Evan Mast 24:36

So that's pretty expensive, and if you use like our normal affordability thresholds, you need like a household income of 120,000 to afford that. So that's like twice the national median. But, you know, suppose the person who moves into that building comes from a different one bedroom apartment, and that one bedroom apartment was like $2200...

Shane Phillips 24:58

Hmm.

Evan Mast 24:59

So when that person moves out, that's gonna open up a vacancy in that cheaper building, the two things that might do, one it just created a vacancy at that $2200 price point, so that's nice, someone could move in and take that. And the other thing is it just increases, I guess the two ways to put it, it increases the supply of units at about that price point, which you would think would push prices down, or you could just save, and more generally, like it kind of loosens the market at that $2200 price point. So it's gonna help out there, it's not just helping out the people that can afford the $3,000 apartment, it's also gonna affect people at this like slightly lower band of $2200.

Right.

And from there, you can just keep doing the same thing. And you can say, okay, the person who moved into the $2200 apartment came from an apartment that cost $1800. And now you're getting closer to something that, you know, the median income could reasonably afford. And, you know, you you keep iterating still, and you say, "okay, where does this chain go?" Does it eventually reach places that are actually you know, like in the bottom quartile of the MSA rents, or something like that. And what I do in the paper is use this pretty cool migration data where I can see like exactly where people move, like, between which addresses. And I try to build out this example that I just gave you in the actual data, and actually look at people living in real new buildings, and say, "okay, where did they move from?" And then find the people living in the old apartments of the people now living in the new building, and say, okay, where did they come from? And I can keep tracking that chain, and I can show you that it does look like, like this chain gradually moves into cheaper and cheaper areas. And because of that, it's going to kind of suck out some of the demand for, you know, say, median income area, and it's going to make housing there a little bit cheaper.

Yeah,

Michael Lens 26:49

I can't believe... Okay, I can believe it, because you're telling me and I trust you. But I find it amazing that you were able to do this with data, you know, like I can follow the concept I could maybe like draw a map for myself on a whiteboard. But like actually going into R or Stata data and like, producing this just blows my mind clear off.

Evan Mast 27:14

I didn't actually, in some ways, the data provider is like idiosyncratically good at preparing the data for this project. Because they make this data to like, worst case scenario sell to some, you know, spam company that's going to send pizza coupons to your house. So they really want the mailing addresses to be good, and with the mailing addresses are really good, that makes it really easy for me to like merge and say, "okay, who's living in this apartment now", and all of the street addresses match exactly. So that's a little nerdy detail for you.

Shane Phillips 27:49

And I think there's like 52,000 individuals or moves or something in this sample, it's a large number, right? Not like a couple hundred.

Evan Mast 27:56

Yes, I had 12 cities, not including LA sorry. And I think I get about 700 buildings, and about 50,000 people living in those buildings.

Michael Lens 28:08

Yeah. And, Shane, can I just clarify one, one point, just to make sure that the folks are following along here. This is not restricting moves within a narrow geography or a neighborhood right, we started talking about neighborhoods in the prior paper, people can kind of be coming from anywhere, right, in these in these moves? Or is there a particular way that you restricted geography?

Evan Mast 28:35

Yeah, this is not about neighborhoods, this is about like a metro area. So I'm finding and I should say, what I find is that these chains pretty frequently do actually reach low income areas. And one thing I find is that these chains also tend to spread out pretty widely across a metropolitan area. So even if you put up an apartment in downtown LA, this chain is still going to hit the suburbs, because eventually someone from the suburbs is going to move into one of the apartments in this chain. And what happens after like five or six rounds of this, is that the people in this chain start to be pretty representative of, you know, the LA metropolitan area. So the percent from the suburbs starts to look like the percent of the LA area that's from the suburbs, the percent that are below median income starts to get close to 50. So that's sort of what happens as you keep going yeah,

Shane Phillips 29:27

That's sort of illustrates how, I mean, here in LA, I think the City of LA, which is, you know, at the heart of it, probably produces, I guess, 70 or 80% of the housing even though we're only 40% of the population. And so kind of illustrates how much work we're doing for the rest of the county to keep prices affordable, not that we're doing enough and not the prices are staying affordable. But you know, these other cities are kind of riding our coattails to some extent. And I want to be clear that what we're really talking about here, is this concept of filtering. This is where homes become more affordable as they age. And there's a paper by Lou McManus and Innopolis recently published where they find that housing in cities that build a lot, the older homes tend to filter down to lower income households in those cities. But in cities that build very little, including LA, they actually filter up and your paper helps explain, I think the mechanism for that; how when new housing is built, some people move into it from older homes, and those older homes become available to someone else. The concern I often hear, I think we've all heard is the new housing is really just attracting people from somewhere else from other states from other metro areas, maybe even from other countries, and just parking their money or whatever. And so it's not really opening up more affordable homes locally. How does your paper respond to that concern? What is the migration data say about that?

Evan Mast 30:52

Starting with just my paper, I find that about 67% of people in the new buildings come from the same metro area. So people certainly move from other areas, but it's it's not like the dominant thing. And the other thing is that, you know, if you put up a new building in LA, some people are gonna move from Cincinnati or whatever. But a lot of those people were going to move to LA anyway.

Right.

So you're still reducing, you know, the pressure on the housing market. I think you even had a tweet about this, Shane, like, if you look at old buildings in LA, 30% of the people moving to them came from outside the area anyway. Right, it's not just a new building thing.

Shane Phillips 31:29

I was asking this question, knowing the answer. That's the secret for all our all our listeners.

Michael Lens 31:33

Wait, are you saying that all of your tweets, Shane, are 100% correct?

Shane Phillips 31:46

They're all prepped for podcasts actually.

Michael Lens 31:48

Excellent. But that's so important, right I, mean, like 67% is a big number. And then, we will never know what the 33% would have done had the building up and built, right. But we have some pretty strong reasons to believe that at least some of the 33% are going to move in to that city or metropolitan area anyway. And they're going to want housing, right. And then they're coming for your existing housing.

Shane Phillips 32:17

If you can afford a market rate housing unit that was just built, you can afford most things. And so price is probably not going to be the thing that keeps you from making that move for sure. There was one other aspect of that, I feel like it's important to reiterate the other point you made Evan, and that I actually I just posted about I think a day or two ago, how 67% might actually seem kind of low to some people, like just depending on where you're coming from. But the reality is that if the same percent as people moving into older units, they're very similar from the data that I dug up. So it's not as though market-rate housing, new market-rate housing is attracting people at a higher or at least a significantly higher rate.

Evan Mast 33:02

Yeah, just this point drives me nuts so I want to talk about it more. Like the people in Boston think that if they put up a new building, all the people from LA are going to move into it. And the people from LA think if they put up a new building, all the Boston people are going to move into it, and it's just total nonsense, right? So it's like, of course, people are gonna come from the same metropolitan area, and the vacant, like parking money thing like, surely Russian oligarchs occasionally do park money in a New York City condo, like, surely that happens. But I'm from Milwaukee, and, you know, I can go read the comments on a new apartment building and like, kind of a scruffy area. And people will be like, "Oh, you know, these are just gonna be vacant investor units". And I'm like, "well, first of all, this is a rental building", and second of all, like the oligarchs don't want get a terrain, you know, in Milwaukee. Like, it's just become this really dominant thing. And it's because those buildings on billionaires' row are really tall. Like, that's the reason it's so salient in people's minds, but it's just not a big thing.

Shane Phillips 34:07

Yeah. I feel exactly the same. I'm constantly making that point about people are going to move where they're going to move. And the idea that the fact that a city built this new shiny building is going to be the thing that causes me to move there, like that's what I'm looking for first and foremost, as opposed to, I just got accepted into a new school or got a new job. And, you know, after making that decision to or being pretty sure I'm going to move, then I look for housing. It's usually I think, one of the later steps in the process as opposed to the first step.

Evan Mast 34:42

Yeah, I totally agree. The one caveat, I will say, and I sort of tried to deal with this in my paper a little bit, is, you know, if you built enough housing in San Francisco, and all of a sudden San Francisco had prices that looks like Chicago, you probably would see more people move there.

Michael Lens 34:57

Oh, yeah.

Evan Mast 34:58

So there's sort of this tension between like, definitely like this one new building that you're fighting over is not going to do this. If you totally reform San Francisco, you probably would get some more people there that would eat up some of the benefits. But in order to actually attract those new people, it also has to mean that the prices did go down enough to attract them.

Shane Phillips 35:19

Yes, which is good.

Evan Mast 35:20

Right? So yeah.

Michael Lens 35:23

Which yeah, hopefully, we can see that a lot of people would benefit from that reduce reduction in prices. And then I think, you know, speaking specifically to like, what a lot of people in San Francisco probably worry about these days on housing is that you would stop a lot of people from leaving the metropolitan area, because housing is becoming so expensive. Certainly, there's a big problem, or there's a hesitancy for a lot of people to want to move there, even if they get a great job, because of housing costs. But then, you know, we know that there's a lot of people that are leaving the the metropolitan area or having to leave San Francisco, to move to more far flung places in the metropolitan area. And that, of course, itself is like this big displacement problem, which I think motivates a lot of, you know, where we started this conversation about, you know, what happens at at the neighborhood level? And in terms of, you know, questions of gentrification and rent growth.

Shane Phillips 36:27

Totally, not to drag this out too far but I feel like we're all we're all feeling this topic.

I had one more thing.

Yeah well, so Evan, you're an economist so I probably don't even need to ask how you feel about rent control. But I'm pretty pro-rent stabilization, at least. And I feel like that this is something that's often overlooked, too, is that, you know, if you like the effects of rent stabilization, one of which is that people are not forced away by rising prices, you know, relative to a status quo, where that didn't exist, it means you're holding on to more people. And presumably, basically, the same number of people still want to move there. And so you have to make room for those people, because you don't have these other ones leaving. And so, you know, whatever your feelings on rent stabilization, if you if you do support it, you kind of have to support more housing too if you want to accommodate the people who want to move here for any reason, or even just form their own household. You know, I think that's a overlooked aspect of all of this, that a lot of the growth happening in cities, is just people being born here and eventually wanting to create their own household. It's not all people coming from New York, and, you know, St. Paul, yeah, those two cities.

Evan Mast 37:44

It's funny, um, you know, the Kalamazoo housing market is very different than the San Francisco housing market. But I've been working with, you know, various people that do housing services in Kalamazoo, and you know, they're trying to use help people use vouchers, or help people use various rental assistance to get a rental unit. And I think because that area is just small, you know, it's maybe 200,000 people in the county, you can sort of like, see the big picture a little more, and, you know, these housing, I don't want to call them housing providers, because I feel like that's like our landlord joke, we're now the the social service providers, like very much see, like, "look, you can dump more money into these programs but the problem right now is we don't have enough units to get these people into them". Like, they might be able to cover the price of it but you know, we just don't have the supply. So like, we do need to build rental units. And I think in bigger cities, sometimes it's like, so hard to feel like you have a handle, you know, on the housing market, and the whole thing to really see that because a lot of things are gonna show up on Zillow. Whereas in a small city like Kalamazoo, you might actually like scroll through the possible listings on like, two pages or something, and it becomes much more apparent.

Shane Phillips 38:57

Hmm. And a question, I think I want to make more of a standard for all of our interviews here is, what do you think is the most legitimate criticism of you know, either both of these papers, either one, you know, maybe we already covered it, but I feel like it's important to address the critiques because there's always, you know, good ones to respond to.

Evan Mast 39:16

Totally. So with this migration chain paper that we just talked about, I think Mike kind of alluded to the critique, you know, take, for example, the 33% of people that moved from another metro area to the building in LA, we're never going to know what they would have done if you didn't put up that building. And that critique applies throughout when you trace out one of these chains, because you can say, okay, someone moved to the $3,000 a month unit from the $2,000 a month unit, but maybe they would have done that anyway, even if we hadn't built the new building. And I tried to do a few things to take care of that. But they're all kind of like, we're never going to know so I'm sort of like taking guesses and trying to say "here's an upper bound, here's the highest I think this rate of new household formation could be" so I tried to be clear about those caveats in the paper. On the paper about like the neighborhood effects of new housing, I mean, I think really generally, it's a quasi-experiment. It's happening out there in the wild, you're sort of like drawing circles on maps, there's a lot going on, it's in a big, messy city. So there's kind of a limit in my mind to like how, you know, none of these studies is going to be perfect. So I'm happy a lot of people are working on this question now. And the other thing is that this paper concerns, you know, these pretty big rental apartment buildings, and I don't think you should apply it to like building a new duplex or renovating something, I think that's different and should be thought about differently.

Shane Phillips 40:48

Yeah, and I actually want to go back, I'm sorry, I just remembered. Anytime we talk about this kind of stuff, people will sometimes want to assume the worst intentions with, you know what the takeaway is. And I just want to read an entire paragraph of your first paper here to make it clear that you're actually thinking about the context, and it's not just like building market-rate housing anywhere under any circumstance, and it will be good. And so what you and your co-authors say on this is, you lead with talking about the impacts of market-rate construction, but then you say, "however, there are a few reasons for caution. First, our findings are specific to the large market-rate apartments and strong market cities that we study. And effects could differ for other types of housing or other areas if amenity effects depend on local context. Second, we are only able to follow outcomes for three years after building completion, though we provide evidence that longer-run effects are likely similar to our estimates" Finally, and my note, I think this is the most important part, continuing the quote, "the actual implementation of reforms that increase housing supply requires changing complicated zoning and land use regulations, policymakers should keep in mind that the particulars of those changes could affect where housing is built, for example, in vacant lots, or through demolition of existing affordable housing". I think it's really important that you're not saying tear down a 10-unit affordable building to replace it with a 14-unit market-rate building, it matters, you know, where you build, who is affected, all of these things matter, presumably building in higher income neighborhoods will have fewer potential negative effects than lower. Just wanted to state that clearly. Mike, did you have anything to add?

Michael Lens 42:39

No, that's good. I appreciate that. Um, and, you know, as both of you were talking, you know, I'm constantly thoughtful of like, you know, what people want to know, is like, "how is this building going to affect my neighborhood", right? And especially if you're in a neighborhood that hadn't seen a lot of investment for many, many years, you know, your neighborhoods have, you know, concentrated disadvantage. Especially, like, they're very wary of like outside investment and their intentions, but like, it doesn't matter how great our studies like we can't tell people what the future holds in their neighborhood necessarily. Almost no matter what happens, like, as Evan pointed out, like, there's a lot going on in these neighborhoods, and these circles on the map that he draws. And these are just, you know, very messy processes at the end of the day, and we were studying usually, like, average effects. And, you know, this is amazing work that Evan and his colleagues have done. And we need more of it to have more and more context where we see these kinds of outcomes play out.

Evan Mast 44:03

Right. Yeah, totally. I mean, I think that's really important. And it's a benefit of the way the housing system is set up now. Well, I should say that the hyperlocal nature of the housing system now can be good for addressing concerns like that, because a lot of times the approval runs through you know, the local city council member or something like that. There's a lot of community stuff, that has drawbacks sometimes but I think it's also good because it people tend to be considering these things in context.

Michael Lens 44:32

We hope so.

Shane Phillips 44:33

And so as we're closing up here, is there anything about these papers that we missed you want to address?

Evan Mast 44:39

No. I think those were... you gave great summaries and I'm happy to have the chance to talk about them a little more.

Shane Phillips 44:43

Cool. Is there anywhere you'd like our listeners to go to read any of your other work or follow your... are you tweeting or anything?

Evan Mast 44:53

I don't tweet too much. I have a Twitter I don't really tweet on it

Shane Phillips 44:56

Good for you.

Evan Mast 44:58

If you want to see my stuff, you can just google me and go to my website and I put my papers up on there. So they're pretty easy to find.

Shane Phillips 45:05

Great. All right. Well, thank you so much for joining us today. This was really, really interesting. We appreciate having you on here.

Evan Mast 45:11

Great. Thank you for having me.

Michael Lens 45:12

Thanks, Evan.

Shane Phillips 45:18

That's it for the UCLA housing voice podcast this time. Thank you again to Evan mast and Upjohn Institute for joining us for such a great conversation. We've got Evan and his co-authors papers in the show notes, as well as a few other articles mentioned during our chat. We didn't mention it during the interview, but Mike Manville, Mike Lens, and I published a summary of multiple recent working papers that tackle this question of supply effect versus demand effect at the neighborhood level. And we've provided a link to that in the show notes as well. The UCLA Lewis center is on Facebook and Twitter. And our website is Lewis.ucla.edu. And Mike and I are on Twitter @MC_Lens and @ShaneDPhillips. And one last time if you like the show, don't forget to give us a rating just that one thing. It's all we ask. Thanks. Bye.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

About the Guest Speaker(s)