Episode 106: Mortgage Lending Standards with Kevin Erdmann (Incentives Series pt. 8)

Episode Summary: Was the housing market really oversupplied in the mid-2000s? Kevin Erdmann says no, and he explains how this misunderstanding is at the root of present-day affordability problems. This is part 8 of our series on misaligned incentives in housing policy.

Show notes:

- Erdmann, K. (2018). Housing Was Undersupplied during the Great Housing Bubble. Mercatus Center.

- Erdmann, K. (2024). Getting Corporate Money Out of Single-Family Homes Won’t Help the Housing Affordability Crisis. Mercatus Center.

- Erdmann Housing Tracker: Mortgages Outstanding by Credit Score

- Erdmann Housing Tracker: Follow-Up: Mortgages by Credit Score

- Erdmann, K. (2021). A Suggested Mortgage Amortization Structure: Fixed Amortization, Adjustable Principal. Mercatus Center.

Housing Was Undersupplied During the Great Housing Bubble

- “Just a few cities are at the heart of the housing supply problem, most notably New York City, Los Angeles, Boston, and San Francisco, which I refer to as Closed Access cities. There are two very different housing markets within the United States: the Closed Access market, where new housing is highly constrained, rents rise relentlessly, and households are forced to make difficult choices as housing expenses eat up their budgets; and the rest of the country, where homes can generally be built to meet demand, housing construction is healthy, and housing expenses remain at comfortable levels for the typical household.”

- “If we add these two markets up into an aggregate market, it looks like a market where rents are relatively level over time. In the 2000s, when housing starts were rising and home prices were also rising to unusually high levels, it appeared as if those rising prices were unrelated to rent, and it appeared that prices were rising at the same time that supply was rising. This pattern, rising prices and quantities, seemed to be the result of excess demand—too much credit and too much money funding too much housing.”

- “Yet few places fit that description. For the most part, there were places where housing starts were low, while rents and prices were both rising, and there were places where housing starts were healthy, while rent and price increases were moderate. If we compare median annual rent and median home price within each metropolitan area, it is clear that rents were an increasingly important determinant over the past two decades of home price differentials between different metropolitan areas. And as shown in figure 5, in this regard, the Closed Access cities have become outliers—much higher rents leading to much higher prices.”

- “The Closed Access cities have become new centers of prosperity, but they have limited the growth in their populations through restrictive zoning and bureaucratic obstacles that make it difficult to build housing. This has turned them into enclaves of privilege, only open to the richest newcomers, who spend nearly half their incomes on rent. This pattern has only developed since the 1990s and is neither normal nor natural.”

- “From 1996 to 2005, across the United States permits were issued to build 6.5 homes per 100 residents. The Los Angeles, Boston, and New York metro areas each approved fewer than 2.6 per 100 during that time. San Francisco approved 3.4. In contrast, other economically prosperous cities that attract aspirational families in search of economic opportunity, such as Washington, DC, Seattle, and Dallas, issued permits at rates higher than the national average.”

- “Contrary to Chairman Bernanke’s assumption, at the national level there was no overhang of housing supply that needed to be worked off in 2011. Indeed, even in 2005 there was no national oversupply of housing. Rather, the American economy was burdened by a shortage of housing, especially in the Closed Access cities.”

- “The housing bubble was concentrated in cities in the coastal Northeast, California, Nevada, Arizona, and Florida. Limiting our analysis to the 20 largest metropolitan areas, the Closed Access cities make up three-quarters of the “bubble” cities, in terms of total real estate valuation. Constrained housing supply was clearly the primary source of high prices in those cities, not excess demand. Prices in the Closed Access cities today remain as high relative to other cities as they were during the bubble because constrained supply is the fundamental reason for those high prices, not reckless credit markets.”

- “Even in other bubble cities with generous building policies, the primary cause of rising prices was the severe Closed Access shortage of housing. This is because those other bubble cities were the main destinations for households migrating out of the Closed Access cities. I call those cities Contagion cities, because in spite of their more generous building policies, they were overwhelmed by the problem created by the Closed Access cities. In the years leading up to the financial crisis, the shortage of housing in the Closed Access cities had become so severe that each year hundreds of thousands of households moved away in search of an affordable home. Many of them landed in inland California, Nevada, Arizona, and Florida.”

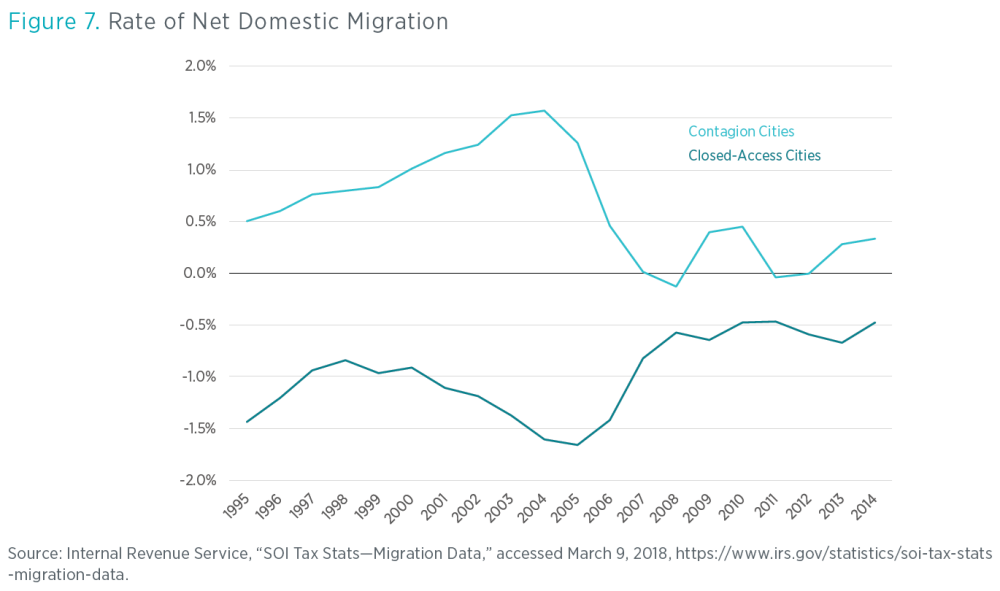

- “Figure 7 compares net domestic migration of Closed Access cities and Contagion cities. Notice that high rates of out-migration from Closed Access cities correspond to periods of large in-migration to the Contagion cities. Credit markets may have facilitated some of the housing activity during the housing bubble, but at its core this was a mass migration event caused by a lack of housing.”

- “For many people, it seemed obvious that there was overbuilding in places like Phoenix. From 2003 to 2005, Phoenix built many homes. Meanwhile, prices of Phoenix homes rose by about 75 percent in just two years. By 2007, however, the Phoenix housing market was collapsing, buried in a mountain of unclaimed inventory. Surely, it was argued, this was a classic credit-fueled boom and bust.”

- “But, for the boom-and-bust story to add up, Phoenix would have had to build enough homes for all of those new households moving in from California, and then it would also have had to build tens of thousands of units in addition to that. It couldn’t. The problem Phoenix encountered was that the in-migration was so strong that even Phoenix authorities couldn’t approve new supply fast enough to meet demand. Building permits in Phoenix jumped by about 50 percent from 2001 to 2004. By all appearances, that is an extremely frothy market, but as figure 8 shows, the jump in new homes tracked virtually 1:1 with net in-migration.”

- “Many of those in-migrants were coming from California. They were moving to Phoenix largely to reduce their housing expenses. In fact, even though migration from California had continued to rise up through 2005, net migration into Phoenix had leveled off. That is because increasing numbers of households now began moving away from Phoenix, which had seen soaring home prices. From 2005 to 2008, migration into Phoenix declined each year while migration out of Phoenix continued to rise. By 2008, net in-migration into Phoenix was less than 10,000 households. By 2006, Phoenix had a growing number of empty homes and a large inventory of homes for sale. But from 2005 to 2008, the number of new homes approved in Phoenix dropped faster than net migration was dropping. Housing supply had reacted remarkably quickly to shifting demand. Even as housing starts were collapsing, rents were rising, as they were in most cities at the time.”

- “The question that needs to be addressed about the housing bubble and the ensuing bust is not what caused prices to rise so sharply. That is a fairly straightforward question, with a standard economic answer. Fundamentally, there weren’t enough houses. What caused the massive out-migration from the Closed Access cities? The answer to that question is also, fundamentally, that there weren’t enough houses.”

- “This leaves one additional question that has been rarely asked, and which must be answered if we are to come to terms with the crisis that followed. If a lack of housing was fundamentally the cause of the housing bubble, then why had housing starts been collapsing for more than a year before the series of events occurred that we associate with the crisis, like nationally collapsing home prices, defaults, financial panics, and recession? And what caused the Closed Access migration event to suddenly stop at the same time as the collapse of housing starts?”

- “For a decade, the collapse has been treated as if it was inevitable, and the important question seemed to be, What caused the bubble that led to the collapse? This needs to be flipped around. Given the urban housing shortage, it was rising prices that were inevitable. So the important question is, Why did prices and housing starts collapse even though the supply shortage remains? And why were housing starts still at depression levels in 2011?”

- “The surprising answer to those questions may be that a housing bubble didn’t lead to an inevitable recession. It may be that a moral panic developed about building and lending. The policies the public demanded as a result of that moral panic led to a recession that was largely self-inflicted and unnecessary. They also led to an unnecessary housing depression that continues to this day.”

Getting Corporate Money Out of Single-Family Homes Won’t Help the Housing Affordability Crisis

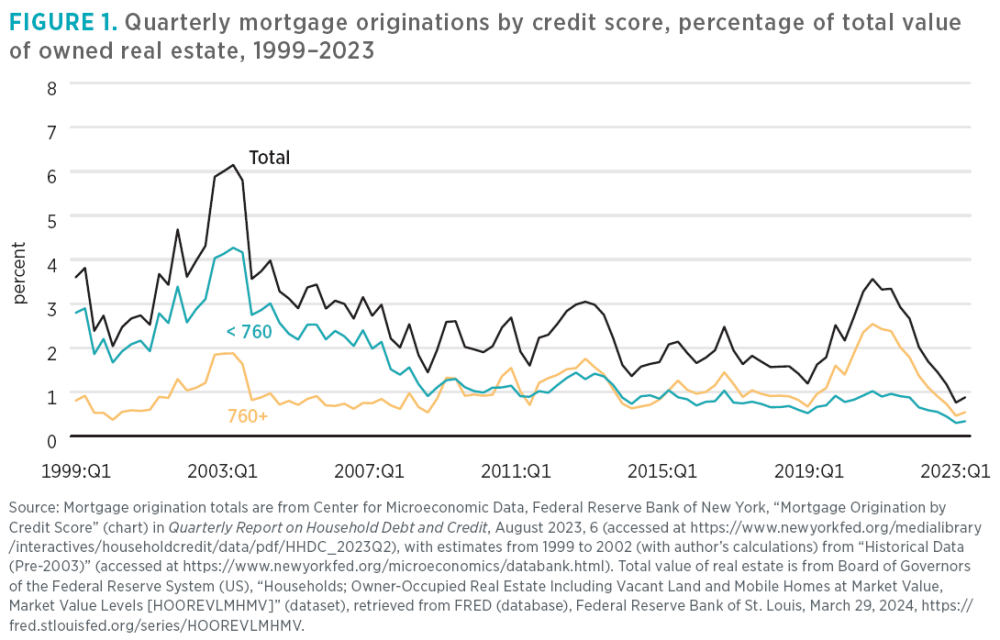

- “Figure 1 shows the quarterly amount of mortgage originations (new mortgages) as a percentage of the total value of owner-occupied housing. (When interest rates decline, many households refinance their mortgages. That explains the bumps in 2003, 2012, and 2019. Note that the 2003 bump predated the subprime private securitization boom, which dominated new mortgage activity from 2004 to early 2007.) Except during the refinance booms, borrowers with credit scores higher than 760 regularly borrowed capital equal to about 1 percent of owner-occupied US housing stock each quarter, both before and after the Great Recession.”

- “Before the Great Recession, borrowers with credit scores below 760 regularly borrowed capital equal to between 2 and 3 percent of the value of owner-occupied US housing stock. That percentage range, as well as the proportion of mortgages originated to borrowers with lower credit scores, didn’t rise appreciably during the subprime boom period from 2004 to 2007. Then, between 2007 and 2009, the proportion of new mortgages going to borrowers with scores below 760 dropped by more than half and remains that low today. (The average credit score among all borrowers tends to be a bit above 700 points.)”

- “This change wasn’t a reversal of the boom era subprime lending excesses. The same pattern showed up at Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association). As figure 2 shows, from 2000 through 2007, the average credit score on Fannie Mae mortgages barely changed. Figure 2 also compares Fannie Mae’s estimate of the value of homes being funded by new mortgages and the value of homes in Fannie Mae’s book of business (homes with mortgages that had been originated in earlier years). Home prices had risen, but the homes associated with old mortgages had similar values to the homes associated with new mortgages. In other words, even though home prices were rising, the mortgages were going to the same types of borrowers in the same types of homes in 2007 that they had been going to for years.”

- “By 2009, the value of homes across the country, including those with Fannie Mae mortgages, had fallen significantly. But in 2009, the average credit score on new Fannie Mae mortgages was about 40 points higher than it had been previously. And, strikingly, the average value of those new homes skyrocketed to well over $300,000—about 60 percent higher than the homes with mortgages from earlier years.”

- “The profile of borrowers served by conventional lenders changed greatly after 2008. Those with credit scores under 760 were much less likely to qualify for mortgages, so the homes those borrowers were likely to live in had fewer potential buyers.”

Mortgages Outstanding by Credit Score

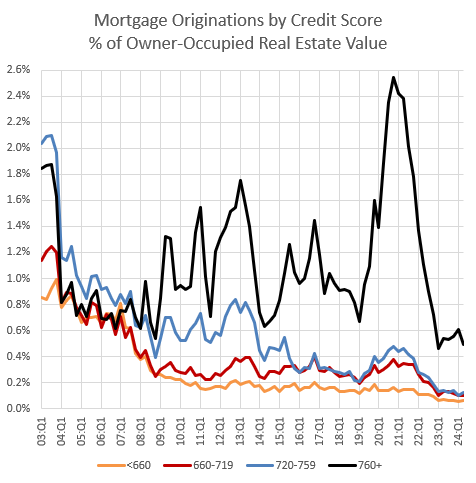

- “At Fannie Mae, before 2008, roughly 2/3 of mortgage lending went to sub-740 credit scores. Then, it suddenly switched, and since 2008, roughly 1/3 of mortgage lending went to sub-740 credit scores. The proportion of lending going to lower credit scores had been pretty stable as far back as I can track the data. The sub-prime/Alt-A lending boom wasn’t associated with a significant change in lending by credit score.”

- “You can see that in Figure 1, from the New York Fed’s Household Debt and Credit report. There was a refi boom in 2003, which tends to increase mortgage activity among the highest credit scores. Then, from 2004 to 2007, during the subprime/Alt A boom, proportions returned back to the long-term norm. The New York Fed tracks 5 bins of credit scores. I have combined the bottom 2. Total activity before 2008 tended to be roughly the same in the 4 bins, and other data finds those proportions at least into the 1990s. Compare that to today, where all mortgage originations to scores under 740 don’t even add up to the quantity of originations to scores over 760.”

- Figure 1.

- “Since 2008, we’ve had a haves and have-nots market. A third of borrowers are locked out of the market. And borrowers who can still get mortgages had a buyer’s market with, until recently, both moderate prices and low interest rates. It was, by far, the best time in recent history to be a mortgaged buyer, for those who were allowed to be.”

- “The have-nots who lost their homes or are unable to buy homes have gotten the worst of the crackdown, because their rents have generally increased massively. The have-nots who were grandfathered in and managed to hold on to their homes ended up with a bit of a windfall because their homes, especially, have elevated prices because of the effect the mortgage crackdown has had on rents.”

The Moral Panic, Its Perpetrators, and Its Victims

- “I have done something like this before – tracking a poor and a rich ZIP code through the timeline of our offenses. It’s time for an update. I hope that this can provide a concise and comprehensive picture of the confusion and devastation of the mortgage moral panic. Here, I will be comparing 2 ZIP codes in Atlanta. ZIP code 30022, where the average income is currently about $190,000, and ZIP code 30344, where the average income is currently about $50,000.”

- “Figure 1 shows the typical price/income ratio in the rich (red) and poor (black) ZIP codes, over time. The price/income ratio in the rich ZIP code approximates a straight line. The price/income ratio in the poor neighborhood approximates a straight line until 2008. The 3x – 4x levels of price/income in the period before 2008 are pretty common for amply housed cities with normal markets, for those of us old enough to remember one.”

- Figure 1.

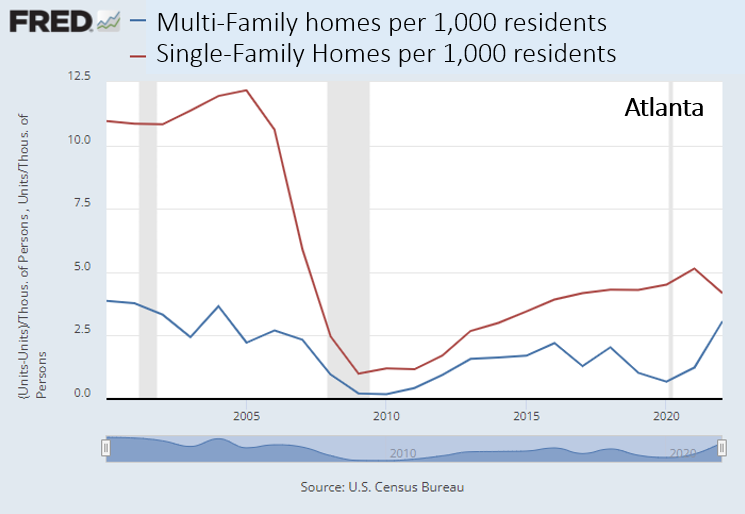

- “Figure 2 shows the rate of new construction in Atlanta for single-family and multi-family.”

- “The decline in building was in low-priced new homes. Builders will claim that they can’t build for the low end of the market because their costs are too high. Costs may be high. Productivity in construction has been poor for a long time and there are creeping regulations. But everything looks like a cost problem to builders. In 2012, when the existing homes in ZIP code 30344 were selling for 1.5x incomes, the builders couldn’t profitably build new homes at that price.”

- “Also, at odds with that, apartments, which generally face more stringent local regulations and are generally smaller and more complicated to build, recovered faster and more completely than single-family construction. They recovered more quickly on price too. Figure 3 compares the Case-Shiller estimate for single-family home prices to the Costar estimate of multi-family home prices.”

- “Others believe there had been a bubble and so they still maintain that from 2008 to 2012, home prices in ZIP code 30344 followed a predictable and unsurprising path … There is a supply version and a price version of that assertion. Baker asserted the price version, which is ridiculous on its face when you look at Figure 1. But, the supply version is just as questionable. Where prices had been relatively stable, as in Atlanta, it was because the lending boom before 2008 had supposedly created a massive construction boom. But, construction in Atlanta was no higher in 2005 than it had been in 2000, and then it dropped precipitously in 2006 and 2007. By the time prices bottomed out in 2012, pick any time period length (2 years, 5 years, 10 years, 20 years) and housing construction for that period was the lowest for the period ending in 2012 than it had been in any other period since data have been collected.”

- “The incorrect explanations tend to all suffer from the same problem. They treat a ridiculously deep disequilibrium as a benchmark. On every margin, the housing market had to correct back from that disequilibrium. The prices of homes in ZIP code 30344 could not possibly remain at 1.5x incomes. And so, all the alternative explanations for what happened after 2012 basically observe things that will inevitably happen after a disastrous credit crackdown (more investors, fewer builders, rising rents, etc.) and construct spurious correlations from them.”

- “One more thing to note in Figure 1 is that price/income has recovered in ZIP code 30344 to a level well above the pre-2008 norm. New homes get built when the prices of existing homes are higher than the cost of constructing new ones. If the Atlanta market was producing new housing across both high and low tiers before 2008, then it should be producing new homes today. But, as Figure 2 shows, single family construction is still less than half the pre-2008 norm. This should be inducing new construction.”

Shane Phillips 00:00:05

Hello! This is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This is episode 8 in our ongoing Incentives Series, supported by UCLA's Center for Incentive Design. Throughout this series we'll be exploring the misalignment between what we say we want our policies and processes to achieve, the behaviors and outcomes they actually incentivize, and potential solutions. Kevin Erdmann is joining us this time to do some mythbusting about the mid-2000s housing market leading up to the crash and the Global Financial Crisis, the policy response in terms of federal mortgage lending standards, and its catastrophic effect on homeownership, rental affordability, and housing production. As we discuss, tightening of lending standards leading up to and following the crash ended up shutting out roughly a third of the conventional mortgage borrowers, people with good credit scores and low borrower risk. Worse, we shut out these borrowers as a response to perceived overlending and oversupply of housing in the mid-2000s, a perception which Kevin shows quite persuasively to be false, pulling together data on housing prices, rents, mortgages, and other data from across the country. The result was a post-2008 crash that was much deeper and longer-lasting than it had to be, that decimated the construction industry even as it kept growing in peer countries like Canada and Australia, that dramatically shrank the market for new construction, that drove up rents, and that disproportionately hurt lower and middle-income households and communities. Throughout this series we've been talking about the costs of being overly cautious, and restricting mortgage credit to this degree deserves to go right to the top of the list. The policy changes that produced these outcomes are largely still in place, but one point of optimism here is that they can also be undone relatively simply. Congress doesn't necessarily need to pass any laws — though I'm sure some could help. According to Kevin, any president since George W Bush could have done a great deal to solve this problem through the various regulatory agencies, it just hasn't been a priority. So much of housing policy happens at the state and local level, but this is a problem only the federal government can fix, and there might just be an opportunity for bipartisan collaboration. This one's a journey, so buckle up. The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Brett Berndt, and Tiffany Lieu. You can reach me at shanephillips@ucla.edu, or on Bluesky and LinkedIn. With that, lets get to our conversation with Kevin Erdmann.

Shane Phillips 00:03:15

Kevin Erdmann writes at a substack called the Erdmann Housing Tracker, and he's the author of two books — Shut Out and Building From the Ground Up — and he's also a senior affiliated scholar at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Today he's joining us to talk about how we came out of the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2008 with much tighter mortgage lending standards and how those changes have influenced housing production, affordability, and home ownership in the years since. Kevin, thanks for joining us and welcome to the Housing Voice Podcast.

Kevin Erdmann 00:03:49

Yeah. Thanks for having me, Shane.

Shane Phillips 00:03:50

So we start every episode with a tour from our guest, a place they know well and wanna share with our audience. So where are you gonna take us?

Kevin Erdmann 00:03:57

You know, I think I'm going to bring up the little retirement communities we have in, I'm in the Phoenix area, and, it's always been, as our kids were growing up, my wife's parents and my parents would always bring RVs out for a couple months and stay in one of these communities and the kids would go stay with them for a few nights, and it's really, I think, interesting part of the housing market in cities like this because it really is, it's a party there, you know, it's there's something going on every night. There's just hundreds or thousands of people sort of, they're basically their own little walkable cities that urbanists talk about. And I think it's interesting how released from the constraints of making a living, so many middle class Americans choose to basically move into these little park models that would blow over into stiff wind, that are in this little, you know, miniature sort of 15 minute city. And I think there's a lot of, a lot of interesting things about where those are allowed. You really can't get approval anywhere in an urban setting to build new mobile home parks if it isn't retired people. There's a lot of interesting aspects of what interesting places they are, what fun places they are to hang out in, and how they're built and where they're built and who's allowed to live in them. One interesting little facet that I think ties into what our conversation will be about is that they also serve as an interesting control group if you're thinking about the effect of lending standards on housing markets because, we have a housing market in Phoenix where there's houses selling for $200,000 or $400,000 or $600,000 and there are houses throughout that range in retirement communities where you have to be 55 or older to live there, and then, of course, there's houses out across the rest of the city. And so you can look at different price points and naturally across the city, for non-retired families, credit access is gonna have a different effect in each of those price levels and income levels. But it doesn't matter if the retired people are buying a $200,000 house or a $600,000 house, they're probably paying cash for it. So I actually was able to extract a few neighborhoods from Zillow data that are strictly retirement communities and compare price trends in those neighborhoods to the price trends in the rest of the Phoenix area. And there's one and only one period of time where price trends in those neighborhoods differed from price trends in the rest of Phoenix, and that was when low priced homes in Phoenix collapsed after 2008. They didn't collapse in the retirement neighborhoods. But when prices inflated before 2008, they inflated everywhere, and retirement communities alike. After the crisis, in recent years where prices become inflated again in a very specific and peculiar way, they've become inflated equally in the non-retirement, in the retirement housing. But from the end of 2007 till 2012, all the retirement home price trends looked like price trends in wealthy neighborhoods. But the poor neighborhoods where people aren't retired,

Shane Phillips 00:07:08

I have grandparents who would go to, I don't think it was Phoenix, but you know, somewhere in Arizona over the winter when I lived in Washington state, and I've never really thought about them as an object of study. But, aside from the research thing, the idea of them being party locations and people just doing stuff every night did not occur to me. But, know, of course, like I that's like a Friday, Saturday thing, but if you don't have a job it can be every day. And if everyone else around you is in the same boat, that's gonna make a big difference. It also occurred to me, something I never really thought about, is how you would never find this kind of place in Los Angeles, for example. It's something that can almost only exist in places that allow you to build housing relatively easily, and of course relatively inexpensively too in the case of the mobile home parks or the manufactured housing. So let's get into this, you've already hinted at some of what we're gonna talk about. But this episode is a little different than usual in that it's really touching on a lot of different publications that Kevin has worked on, not just one or two. He's a pretty prolific writer. Rather than call out any of these publications in particular here at the start, I'm just gonna make sure that they're linked in our show notes so people can check them out in more detail if they're interested. When I mapped out this Incentives Series, I had this arc in mind moving from one broad topic to another, and I had most of the specific episode subjects and guests figured out ahead of time. But I did leave things open to revision, hence why we ended up doing six episodes on building codes and standards when I initially only planned three. I say this just to make the point that this series has evolved somewhat organically and probably the most unexpected, unplanned theme that's arisen from all these conversations is the unintended consequences of being overly cautious. We've kept coming back to how past a certain point, protections against exploitation or danger or a low quality product can make it so that that product becomes impossible to provide at a reasonable cost, and so we get too little of it at too high a price. And we don't actually provide much additional quality or safety in the bargain, as we've seen. For the past decade, Kevin's been beating the drum on another facet of this problem in the housing market, which is the tightening of mortgage lending standards following the housing crash and Global Financial Crisis of '07-08. But before we get to that, if Kevin is known for one thing, it is probably his argument that the thing we call the housing bubble of the mid-2000s was not really a bubble at all, but in fact, a housing shortage. It was a housing shortage, we failed to appreciate because it was limited to just a few metro areas across the country, but the impacts did not stay contained to those places, and they spread to other metros over time. This is not the main topic of our conversation today, but I think it's really important context that helps explain the mortgage lending reforms that came later. And besides all that, it's just a fascinating argument that more people should be aware of. So Kevin, could you give a succinct summary of that argument? I think the distinction between Closed Access metros and Contagion metros is really the key concept here, so let's make sure we touch on that. And for listeners who want to read more or look at some of the charts illustrating these points, I'll put in the show notes your 2018 paper titled, "Housing was Under Supplied during the Great Housing Bubble."

Kevin Erdmann 00:10:40

Yeah, so, I think the important distinction here, sort of the motivating core of the story is that there were two very different types of cities during that housing boom. There were what I call the Closed Access cities, which is a very specifically New York City, Boston, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. And San Jose, of course, along with San Francisco. And those cities are, basically across the board, just have such clamps on housing supply throughout the metropolitan area that they've effectively stopped growing. They don't have the ability to really grow at this point. So they are cities, the poorest neighborhoods are where the prices and rent go up the most. New York City this year, probably 200,000 families will have to move away. The price of housing across New York City is basically the price it takes to get the 200,000th family to move away. and curiously what happens there, we naturally tend to want to spend a given percentage of our incomes on housing. And so even with a flat population, if our real incomes go up, say 1%, people want to consume 1% more housing per capita, and it works out through the market in all sorts of different ways. but the thing is, when growth is higher than that — and these cities are really only capable of growing their housing stock, by about 1% — then it actually creates this weird countercyclical population and migration trend where the better off we are, the more people have to move away from those cities to settles the housing market there. And so it creates this basically a Malthusian limit, an arbitrary Malthusian limit with all the cultural and economic implications of that. You get, progressives in San Francisco that'll say, "oh, it's the tech corporations that are to blame for the housing crisis because they pay their workers so well. And since they can afford better housing, then it makes it harder on everyone else." And that's really a, weird thing for a modern person to say, but somebody that's stuck in a Malthusian context, it seems natural, because at some point you really, you don't have growth potential. You just have trade-offs.

Shane Phillips 00:12:43

It sounds sort of like a similar thing happening, but at the opposite end of the spectrum to the Homelessness is a Housing Problem thesis, where rising rents — and rising affluence, which leads to rising rents — if you're not able to build more housing, leads to actually increasing homelessness. And you would think a more affluent society would have less, but that's not what happens. But what you're saying is that the top end of the market or the higher ends of the market, when people get wealthier, they want to consume more housing. And so part of why a lot of people have to move out is if people are consuming more housing, but the housing supply is not growing, you might have household sizes actually decreasing.

Kevin Erdmann 00:13:22

Yeah. So that might be an adult still living with their parents. It might be a half a dozen, software programmers, have been sharing in an apartment and one of them gets a raise and now he can go buy a place. It may be that somebody buys a duplex and tears it down and builds a single family home in its place. Whereas if they bought a single family home and wanted to turn it into a duplex, they'd spend 10 years at the city council. So yeah, so you actually get this countercyclical population shift in those cities. So as we're going through the 2000s and the economy's growing, each year there's more and more families that had to move away from those cities to settle those markets, wherever they were. And so we have sort of a compositional problem. Families that — especially families with low incomes that live in Los Angeles today — have self-selected as people willing to pay extortionary rents because there's something about Los Angeles that they can't give up. And really, the tip of that iceberg is, homeless people who even after they lose shelter, have something important enough about Los Angeles that they can't, give it up. For every homeless person, there are 50 families that have chosen... that have self-selected to be displaced. And for some families that's really easy, for some families it's really hard. And in fact, one of my sort of little play indicators that I look at is U-Haul rates between Phoenix and Los Angeles. It tends to be about three times more expensive to get a U-Haul out of Los Angeles than it is to get from Phoenix to Los Angeles. And I consider that a recession indicator. If that gap goes lower — if it's not quite as expensive as normal to get a U-Haul out of LA, I consider that a recessionary indicator. The better off we are, the more people are displaced from LA, and when we're not getting better off, then more people are able to stay there. And so basically, the other, the Contagion cities — which are cities in Florida Arizona and Nevada — those were the destinations for those displaced families. So the shortage in the Closed Access cities is what creates the demand boom in the Contagion cities.

Shane Phillips 00:15:21

Contagion metros tended to be places that were relatively close to the Closed Access cities. Not in all cases, but places like Las Vegas, Phoenix, Florida's also a big one on there — presumably overflow from New York City Boston. Sort of the East coast version of this.

Kevin Erdmann 00:15:39

Yeah, yeah. So in the West Coast it's a lot easier to see. It's a very— a wave out from the coastal California cities to, as you get farther away...

Shane Phillips 00:15:47

Yeah, just one or two states away.

Kevin Erdmann 00:15:48

Yeah, yeah. Now, interestingly, that's part of the reason why Texas sort of sat out they're really not an important part of that 2000s boom and bust. But more recently, the outflow from San Francisco to Austin was much stronger than it had been previously. And so Austin sort of became a Contagion city in the COVID period. But basically, when we're growing, the rest of the country actually has to sort of overproduce housing and overproduce economic growth to take in all these housing refugees from the Closed Access cities. So basically what happens in Arizona and Nevada and Florida is they had this surge of inmigration that they actually weren't able to keep up with. They were building houses for fundamental reasons that thousands of people were moving in. And some of those people had a pocket full of cash 'cause they sold a house in Los Angeles or New York. And then suddenly that migration just dissipates. And I think it's an interesting period, that 2006 and '07 period. It was really interesting because the Fed was purposefully trying to slow down construction because they thought the whole story was we had a lending bubble and a housing bubble, and they thought we were building too many houses. And they were literally sucking cash outta the economy until construction started to fall. And curiously, what happens there... one of the first things that happen is that that migration event dissipates. People weren't moving from Los Angeles to Phoenix because they didn't have a job in Los Angeles. They were moving because they didn't have a house. And so it was actually... the challenge for Phoenix was to have houses and jobs for all these people moving in. And it actually reduced those challenges as slowing down the economy led to those people staying in Los Angeles. So you get these really strange cyclical effects where, from 2006 to 2007, employment growth in Arizona goes from like 6% to zero. While that happens, the unemployment rate in Arizona actually went down. It was actually less than 4% as we go into the official recession, even after losing that much growth. And so I think partly what happened is we were actually very deep into a lot of the things that would normally be lead leading indicators of a coming recession. And in addition to everyone panicking about the supposed housing bubble, the aspects of that bubble and what it does to the economy sort of hid some of those early indicators of a recession coming. But one of the great early indicators of a recession is collapsing housing starts. And housing starts were already well below where anyone in any other frame of mind would've said, "oh, this has gone way too far. We need housing starts so we don't go and do a recession." And instead, we had this moral panic about a bubble we thought was happening. And so the Fed actually just continued to push ahead for housing starts to continue collapsing.

Shane Phillips 00:18:36

So we had these Closed Access cities — like Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, et cetera — that... demand was increasing. People were earning more money, but they were not building much more housing. And so we had this flow of people who just made the decision, or the decision was made for them in some cases, they just could not continue to afford the Closed Access. Someone had to leave given the rising demand, and the lack of supply to compensate. And a lot of those people went to places like Nevada and Arizona and Florida. And I think the key point for these Contagion metros is we see places like Las Vegas and Phoenix as having overbuilt during, the 2000s, and that was a problem we needed to solve. But what your research shows is, in fact, relative to the migration that was happening into those places, they were, for a while, just barely keeping up with demand. And for a very short time, they actually fell behind. And so even in these places we think of as building the most housing, being the most oversupplied, they were kind of holding steady at best. Whereas the highest demand places like Los Angeles were not keeping up at all. You don't see a boom in production at all during the 2000s in places like LA and New York. And so, when you put all that together, you have some places barely keeping up, other places, not even trying to keep up. That is a housing shortage. It just looked a lot different than the one we've been more familiar with the past 10 years or so.

Kevin Erdmann 00:20:07

Yeah. And there's some tricky aspects of that because a growing city like Phoenix or Austin may be growing the housing stock by 3% or 4% a year. And so like in Phoenix it maybe went from 3% to 4%, but population growth had gone higher than that. Nevada actually really didn't have a supply response at all. Nevada was a very fast growing city, but when demand spiked, in the short term, there was actually really no increase in construction activity in Nevada. Which is sort of funny because people will talk about how they built all these homes nobody needed in the desert, and I don't know why people say that without apparently ever having looked at a chart. But it's just so broadly...

Shane Phillips 00:20:48

People don't look at charts.

Kevin Erdmann 00:20:49

Yeah, it's just been so broadly assumed and restated that people are convinced that builders are speculatively building years worth of supply out in the desert. So those cities are building— were building 3% or 4% growth every year. The thing is, New York City and LA were building maybe a half a percent growth a year, and maybe they did increase that to three quarters of a percent. And so the locals there will tell you, "oh no, you don't know what you're talking about, it was a building boom. I've never seen so much activity."

Shane Phillips 00:21:16

Yeah. Which may very well be true, and it was a 50% increase, but it was not, not nearly enough still. I do want to clarify one thing though. I don't remember if I saw this in something I read of yours months, if not years ago, but is there another city? Is there like a Open Access city? How do you classify the places like Texas, and what was their experience? Because I think most people's understanding of the housing bubble, the housing crisis through the 2000s or the end of 2000s was that everywhere saw prices shooting up at roughly equal levels. And that's not true at all, right? There actually was not a huge run up in prices in some markets.

Kevin Erdmann 00:21:59

Yeah. In fact, most of the country. in Shut Out, I had basically three categories, Open Access, Closed Access, and Contagion. And Open Access was probably close to two thirds of the country. Closed Access is probably about 25%, and then about 15% would be in the Contagion areas. And it's very easy to tell those markets apart because during the boom times the Open Access cities construction rates were basically flat. They were just building at the same rate. They didn't have a big boom and prices and rents were relatively stable. If anything, in some of those markets like Dallas and Atlanta, slightly elevated construction was actually bringing rents down in those markets and prices were relatively stable. And you can really see this when you look inside the markets and I would encourage anyone that's doing housing analysis to not stop at the averages, because in the Open Access cities, the average price to income ratio might be 3. And if you look inside those cities, it's about 3. It doesn't matter if you're in the poorest neighborhood or the richest neighborhood. The richest neighborhoods might typically be 3, and the poorest neighborhoods may be 3.5 or close to 4 in the cities with the steepest gradients. That was true in Phoenix. In Phoenix, in 2002, across the city, prices were about three times incomes. Now in Phoenix because it was a demand boom, a demand boom has a very distinct picture. By the end of 2005 in Phoenix, prices were about five times incomes, and it was still equal across— the poorest neighborhoods were five times income, prices in the richest neighborhoods times incomes. There's nothing in Phoenix that's going to maintain that — that was truly bubble pricing. It was driven by the shortage in California, but it was truly a bubble in that those prices weren't going to be sustained. And you can tell when they aren't going to be sustained because they go up in the richest neighborhoods as much as in the poorest neighborhoods. That also happened recently when prices were temporarily high in Austin. In Los Angeles, prices at the high end are, say... the richest neighborhoods are maybe four times incomes. Prices in the poorest neighborhoods are more like 15 times incomes. And so you can really see, when there's a shortage, families are all making these compromises across the market. Sort of trading away amenities in order to make the budget work. And that all piles up on the poorest residents in the cheapest neighborhoods, so that when you have a shortage condition, it's the cheapest homes where rents and prices elevate the most.

Shane Phillips 00:24:25

In part because that's where there's the most desperation to hold on, right? Like if you're in the middle you can trade down, if nothing else. But if you're at the bottom, it's a choice between leaving and paying more. And for very good reasons, a lot of people will do whatever they can to avoid leaving.

Kevin Erdmann 00:24:40

Yeah, yeah. And now moving ahead to today, because we collapsed construction across the country through mortgage regulation, so that the supply conditions changed uniformly across the country, now every city looks a little bit more like Los Angeles. So now, in Phoenix, first the bubble corrected and it went back to three times incomes across the city. But now in Phoenix, homes at the high end are three times incomes, and at the low end, they're seven or eight times incomes. And that's true to some extent in Dallas and Atlanta and Indianapolis. And, because we sort of created this, crevice in the American construction industry for 20 years, and we spread the shortage nationwide.

Shane Phillips 00:25:23

So I think that because we have this idea of the housing crash being driven by lending too much for mortgages, and in particular lending to people who shouldn't have been getting mortgages — subprime lending. Some people might hear this explanation that you're offering and interpret it as dismissing concerns about lending to people who shouldn't have been borrowing, which did screw over a lot of people. But I think that's not your message, right? Subprime lending was a serious problem, and we were right to restrict it. It's just that too much lending in general does not stand up to scrutiny as the cause of the housing crash, and the recession, because we weren't actually overbuilding overall. Is that right?

Kevin Erdmann 00:26:05

So, yeah, there was definitely reckless lending that created a number of problems, and probably had a marginal effect of increasing the average home price by maybe 8% or so before 2008. So I would say that's all true, and then I would surround that with a number of caveats. The first caveat is that real home prices have increased by more than 50%. The other 42% has been broadly blamed on loose lending when it was really due to these fundamental causes. So there was a lending molehill on the side of a shortage mountain. The other caveat is then that means that the reversal of prices wasn't an inevitable result of loose lending. Loose lending wasn't to blame for the collapse. And there's this sort of begging the question that happens that everyone that believed it was a hundred percent lending bubble then feels like they were confirmed by the collapse itself. And I think there's an important distinction to be made here 'cause there's two very easily distinguishable credit events that happened. There was the rise and fall of privately securitized, non-prime mortgages from late 2003 to early 2007. And that was associated with a marginal rise and fall in prices of about 8% on average across the country. And then there were the federal agencies who basically maintained historical standards of borrower quality throughout the boom, and then after doing that — after sort of losing market share to the subprime market — then, instead of coming in to stabilize the market in 2008, they cut off basically the bottom third of their traditional market. And so there's cities across the country, basically anywhere between DC and Denver, where prices and construction activity had been normal before 2008. And then in every city simultaneously, first in early 2006, construction started to collapse because that's what the Fed was aiming for. And then when construction could have started to return, then very distinctly in 2008, the federal agencies abandoned the bottom third of their traditional market. And so at the same time that they did that, then home prices in all those cities between DC and Denver that didn't have a bubble, the average home price in those cities declined by say 25%. But that was actually an average of high tier home prices in those cities that were pretty stable through that period, and low tier prices in a lot of cities were down like 50% from what had been pretty normal prices to begin with.

Shane Phillips 00:28:26

Because the market for those lower tier homes was that bottom third of people who could no longer get mortgages. mortgage credit.

Kevin Erdmann 00:28:33

Yeah, yeah. And so then the other caveat that comes back around to the subprime issue is that under those conditions where the federal agencies basically sucked $5 trillion regressively out of American real estate collateral, that made the performance of the subprime loans even worse because the collateral got ruined. But the collateral was ruined because of the agencies. And I actually think Ben Bernanke was right in 2007 when he said that the subprime crisis was contained and wouldn't be a problem. It wasn't the subprime boom that created the crisis, it was the agencies and it was what they did after he made that comment.

Shane Phillips 00:29:09

Hmm. So what I'm hearing is, yes, reckless lending was a problem, but actually the cutting off of credit to perfectly worthy borrowers probably made the crisis worse because a. It lowered values at that lower end of the market where a lot of the subprime borrowers had bought housing. And so it actually lowered the value of the housing they had bought more, and pushed more of them underwater and further underwater than they might have been otherwise.

Kevin Erdmann 00:29:38

Exactly. That's one aspect of it. And if you go back, there's some interesting literature where, because eventually it got to the point where even within prime mortgages default rates were rising because it was this deeper, new thing that happened. It wasn't because of the reckless lending in 2005 and '06 that this all happened. And so people were looking at credit scores and saying, "well, credit scores must not be as useful as we thought because they don't seem to be as correlated with the default crisis as we, would've thought they would be They didn't know that when they were asking those questions, but it's because default risk wasn't the reason people were defaulting. Borrower default risk wasn't the reason people were defaulting. People were defaulting because the federal agencies pulled the rug out from under a third of the country.

Shane Phillips 00:30:20

Another thing I think people may not be aware of is how different the response of the housing markets in Canada and Australia were through the 2000s— late 2000s and the 2010s, and what that says about the different responses. And we will get to the specific policy responses here in a few. But what was the experience that they went through during and after the Global Financial Crisis and how does it compare to case in the US?

Kevin Erdmann 00:30:50

Yeah, you're right, they make very useful counterfactuals. And in fact, I think it's sort of odd that the American experience is treated with such fatalism, because it was really only us and Ireland and Spain that had this big boom-bust paired event. There were many, many countries like Canada and Australia, like the UK, a few other European countries, that had prices just as elevated as they were here, and none of those other countries saw any decline in real home values in 2008. And so I think the Canadian market is very similar. If you look at the history of the Canadian market in terms of price trends, that's basically what the United States market would've looked like if we didn't have the mortgage crackdown. And they have the same basic problem. There's a big difference between home prices in Calgary versus Toronto and Vancouver. I don't think Toronto and Vancouver are quite as clamped down as New York and Los Angeles are. They have a little bit more growth potential. But also we have probably a lot more cities that can serve as second tier options for people. So in some ways I think we have it worse, in some ways we have it better, but I do think it's a little bit tricky to look at. For instance, it's very easy to look at the price trends and say, "oh, well look, Canada is even worse than us because prices have kept going up and they're even higher there. But really what we did is the mortgage crackdown lowered prices in the United States, that collapsed construction — it created a bunch of construction unemployment. Also, by the way, in Australia and Canada, construction employment kept growing. But when we lowered our prices, that ended up leading to rent inflation in the United States because we stopped building. And so you could look at price trends and say we made homes more affordable in the United States than in Canada. But really, homes are less— they're actually less affordable for renters now, and more affordable if you can run the gauntlet and get approved for a mortgage.

Shane Phillips 00:32:42

Mm. Mm-hmm. So, summarizing here. Basically, we misdiagnosed housing supply booms in these Contagion metros as an oversupply driven by excessively lax mortgage borrowing standards, when in fact there were an entirely rational and, and really appropriately sized response to a huge wave of migration out of the Closed Access metros. And once we decided that loose lending was the cause, the obvious solution was to tighten those lending standards, which we did starting in 2008 or so to great effect. I pulled some stats from a few of your papers that help illustrate the effect of those stricter standards on borrowers that I'm gonna share here really quickly. So these refer to credit scores, and for anyone not very familiar with how they work, the scores we're talking about here range from 300 to 850, and a score in the mid-700s or above is considered very good to excellent. 670ish to 740ish is good. And below that, you're in fair to poor territory. The specific score we're talking about here is the FICO score. And from 1999 to 2007, about two-thirds to three-quarters of the value of mortgage originations was for borrowers with credit scores under 760. This is the total value of new mortgages taken out in a given year. So most of that value was people with good, but not very good, not excellent credit. The rest of borrowers had scores of 760 or above. Since 2008, the ratio shifted from around 70/30 in favor of borrowers with lower credit scores to more like 50/50 or even 40/60 in favor of borrowers with higher scores. You could see a shift like that if borrowers with excellent credit just started taking out more mortgages, but that is not what happened. The shift was caused by people with average to good credit taking out many fewer mortgages. As you said, Kevin, your odds of getting a mortgage as a person without great credit were much lower after the global financial crisis, and that is still true today, almost two decades later. Another way of looking at this is the average FICO score for people taking out mortgages. Kevin has a graph of FICOs for people taking out mortgages backed by Fannie Mae, and that means these are conventional mortgages that exclude the sort of subprime, less credit worthy borrowers that we were presumably trying to protect coming out of the housing crash. So from 2000 to 2007, the average FICO at mortgage origination was steady around 710 to 720. Again, mortgage origination is just the time at which borrowers are issued their loan. So pre-crisis, we are stable around a 715 average FICO. Then between 2007 and 2009, you see this huge jump up to around 760, or about 45 points. It stays there for a few years, and then it dipped to around 750 in 2014 and stayed at that level through 2019. So more than a decade after the crash, it was still up about 30 to 35 points above its pre-crisis average. I'll remind listeners that this is the average credit score for conventional mortgage borrowers, not the people we think of as high risk, or the subprime borrowers we were trying to prevent from being taken advantage of. And since there's a big range of scores below 760, I'll also note that this was not just people at the bottom end falling out, like a bunch of people with a score of 600 being screened out. In another figure, Kevin shows that while originations fell most for people with credit scores under 660, they fell nearly as much for people with scores from 660 to 719, which is good territory, and 720 to 759, which is people with just solidly good credit. There are a lot of other stats I can point to from various posts and publications by Kevin and others, but the takeaway here is just that the average American has a much tougher time getting a mortgage today than they did in decades past. It's not really disputed as an idea, but part of what makes Kevin's work important is that it shows that these heightened mortgage standards were not a reasonable reaction to too much lending to people who shouldn't have been borrowing. It hit a whole lot of people who were perfectly capable of paying back this debt if they have the opportunity to get it. So that's the background. We probably won't be able to stick to this structure perfectly, but I'd like to do the rest of this conversation in three parts. First, I wanna talk about how these lending standards actually changed. Second, we should interrogate the data a bit and make sure we're not misinterpreting it. And then I want to talk about what this all means for housing supply, affordability, and home ownership. And then of course, some of the things we should do about it. So let's start with the how. What caused this big rise in the average credit score of mortgage borrowers and the big drop in the share of borrowers with scores under 760? What changed both in the realm of public policy and in the private sector?

Kevin Erdmann 00:37:52

before I get to that answer, another interesting aspect of the changes when you go in and look at Fannie Mae's books, in particular, is they publish some details on their existing book of business of mortgages that they had originated in earlier years that were still on the books. And they publish data on the new mortgages that they have originated each year. And through that boom period, home prices were of course going up on average. But every year up to 2006 and 2007, the average home price of families getting a new Fannie Mae mortgage was the same as their estimate of the value of families that still had old mortgages. And by 2007, that was about, $250,000 in both cases. Now from 2007 to 2009, the value of existing mortgage borrowers at Fannie Mae went down to about $200,000, in line with how home prices had moved across the country. But by 2009, the average value of homes getting new mortgages from Fannie Mae was something like $ 325,000. That detail lined up with the detail about the changing lending standards, really creates a striking picture... they were giving out mortgages for houses and neighborhoods where houses cost $350,000. They weren't giving out mortgages in neighborhoods where homes were selling for $200,000. And in fact, as you sit with this data and think about the narrative, it becomes hard not to question whether that was the entire reason why those other homes were $ 200,000 instead of $250,000. You could actually divide it into a top and a bottom. They used to make loans to $325,000 homes and $150,000 homes, and you sort of take the bottom half of that out, and so the average goes up to $325,000 in 2009. And they're just not making mortgages on those cheaper homes, and then the average of all those old homes has declined 200,000. I actually put the entire $5 trillion loss of real estate value on net, at the feet of the agencies.

Shane Phillips 00:39:59

And it wasn't that the agencies or the lenders were saying, this home's worth too little, we're not gonna lend to it. It was the people who would've bought those homes tended to have lower credit scores and they were just not getting mortgages anymore. So no one was really around to buy those homes.

Kevin Erdmann 00:40:16

Yeah. And in that early 2008, 2009 period, you really do see it in denial rates. There were people trying to get mortgages for those homes, and they were just being freshly denied.

Shane Phillips 00:40:27

Mm-hmm.

Kevin Erdmann 00:40:27

To your other question, it's sort of a tough question to answer. So there's a few things, like in October 2006, the Fed published what they call the interagency guidance on non-traditional mortgage product risks. And that probably, had a lot to do with the subprime markets collapsing. But again, in my point of view, the subprime markets weren't that important, to the crisis. That led to that whole market basically disappearing, and it probably lowered home prices a few percentage points across 2007. So then you get to 2008. In early 2008, there's a change in the fair lending standards, what they call Regulation Z, and regulators started making changes to what they call ability to repay. And there's a number of boxes that they started adding, even in prime lending. Boxes you needed to tick off — limits to the spreads you could charge, mandates on underwriting you needed to do, making them be more detailed about confirming incomes. And, that was happening to a certain extent by 2008. Now, what gets a little bit tricky is a lot of that doesn't necessarily get really codified, of written down and officially made as part of lawmaking until... Dodd-Frank really happens in the summer of 2010, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is created to manage all these regulations. But the change had happened before Dodd-Frank was passed, and you see it very distinctly from the end of 2007 to early 2009, whether it's at Fannie Mae or whether it's across the market more broadly. There was just a steep one time spike in the average, credit score of a borrower getting a new mortgage over the course of 2008. And I think a lot of it is informal... Hank Paulson was the Treasury Secretary at the time. He makes it very clear in his memoir that he was actively engaged in pulling back mortgage lending, and taking over Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and limiting their risk over that period. So they were taken into conservatorship, taken over by the federal government, in August of 2008. But it's hard to pin it down because there was sort of a thousand straws thrown on the camel's back at once, and there was not a single person in this country that was gonna make a peep about it. Nobody was ever going to complain in 2008 that Paulson was pulling back on the GSEs too much. In all of the memoirs that everyone writes, the entire tone of the memoirs of the policymakers is defending themselves that they weren't just turning the screws tighter and tighter, defending themselves that, "well, we had to do it this way. Don't blame me for not hurting people ." And so I just think a lot of that is sort of in the details and the informalities in the back rooms of Fannie and Freddie, where the underwriting rules are getting made up, it doesn't necessarily draw itself from some bill that Congress has passed that lays out what credit score should be approved, or what kind of income should be approved for a mortgage. And I think you could just see it so universally in the way people were acting then and the way people look back on it now. Even to this day when I suggest that we should or could have tried to avoid any of that collapse, the most common response is very much a sort of, how dare you, "oh want the NINJA loans back again." People still have a very strong reaction to interpreting the entire thing as one big bubble and bust, and they don't even want to think about it more carefully.

Shane Phillips 00:44:04

Yeah, I think you've described this as sort of a moral panic in a way, where it's just, all at once, everyone comes to the same conclusion, and the idea of questioning it is just off the table essentially. And so everything that follows from it— once you've decided the problem was too much lending, too much building, then anything that results in less of those things is necessarily good.

Kevin Erdmann 00:44:27

Yeah, yeah. To me, details that are a little bit crazy looking back— that whole period where TARP...

Shane Phillips 00:44:34

This is the bailout package? Yeah, the troubled Assets Relief package

Kevin Erdmann 00:44:37

Yeah. In September of 2008, all this public debate about that, for that entire month, the Federal Reserve, they had actually stopped lowering rates through most of 2008. And at the September meeting, their target rate was still at 2%, and they held it at 2% because they said they were afraid of inflation and markets immediately collapsed as a response. And while everyone was debating TARP, nobody even thought to suggest that maybe they should have actually lowered the target rate. Of course, they eventually lowered it to zero months later. And you sort of go forward from time, there's the famous Rick Santelli rant on CNBC that sort of led to the founding of the Tea Party movement. That's in February 2009. That's five months after the financial crisis. And the entire point of that rant was, "don't you dare stop home prices from collapsing. These people need to pay." I mean, it was angrily, that that's how he felt. And then you go forward, the Occupy Wall Street movement didn't even start until October of 2011 when working class home values in Atlanta were selling at a 50% discount. And still in 2011 their main point of view was, "do not let these bankers get their hands back on these— giving mortgages to these families."

Shane Phillips 00:45:54

Mm-hmm. Something that I did not appreciate is how much of mortgage policy is... I guess not informal necessarily, but not enacted through law. It's decisions by different agencies that don't require Congressional approval or that kind of thing. Dodd-Frank, obviously that is a law that passed in 2010. It did a lot of things around financial services and protections, created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. But I do want to push on this a little bit because some of the things I heard you say about... stricter income verification — t hat does not strike me as something that would cause people who had good credit — not great, but good credit — should have been able to get a loan — would be screened out of the process. And so can you say a bit more, like, even if it was just guidance, what are the kinds of things that would've caused these people to just be denied outright, and just no longer be able to get credit. And this feels incomplete to me because if it was just these informal decisions or this guidance, and there's flexibility on the part of the lenders I would've imagined by now that at least the conventional mortgage lenders would have lightened up a little bit, and realized we do not need to be so strict about this. This is just cutting our own business and lending to many of these people would not increase our risk.

Kevin Erdmann 00:47:20

Yeah, you know, in some ways I probably, unfortunately just am not going to have a satisfying answer. I think probably it would be interesting to find bankers who appreciated the broader narrative of my framework and were active in the market at the time, and they would have a lot more detailed replies as to which of those straws were the ones that broke the camel's back. And in a way that's partly what I'm saying. The Ability to Repay rule and the Regulation Z These surely must have been a part of the process. It's hard for me to point to anything in particular that changing that one thing would've been important. In a way, I think it's a whole host of things that happened at one time. And one thing that I notice occasionally... like you might see people who claim, "oh, lending standards didn't really tighten because, for instance, debt to income ratios" — they tried to limit that in like, anything above 40%... if more than 40% of your income's going to debt payments, that starts to be considered risky territory, and there's limits on how much lending the agencies can do when it gets that high. But then what happens is, this sort of mountain of new rules meant that if you didn't have clean W2 income going back a couple years, then they just simply weren't allowed to count it as income. So there's two people sitting across a desk from each other that both know exactly what their financial situation is, but the number you put on the form now doesn't allow any discretion on that, and there's just a rule now that if you made $30,000 last year working odd jobs, that just doesn't count.

Shane Phillips 00:48:54

And is that still a rule that's in place? place

Kevin Erdmann 00:48:57

I'm not a hundred percent— I think so. I'm not a hundred percent sure. There's been some tweaks in the recent rules about which mortgages the agencies will buy and what the regulations are. Up until the last couple years, basically what happened is that... in addition to limiting the spreads you could charge, increasing the mandates of things you had to do in the underwriting process, there were sort of backward looking... if a bank made a bunch of mortgages and there was a recession or something, and a lot of them defaulted, there's sort of backwards looking judgements now, and if those were determined to be predatory in hindsight, then there's sort of a undefinable amount of, penalties and fines that you would be subject to.

Shane Phillips 00:49:38

So there's a caution on the part of the lenders, less because they're worried about the borrower defaulting and more if things go wrong — which like, some percent, or fraction of a percent of people will default on their loans. Even if they're a good credit risk, it's not zero. You're at much higher risk as the lender of that kind of tail risk of maybe they sue, maybe we didn't do everything as strictly as we possibly could, and we're gonna be liable even though we felt like this person was still a good borrower.

Kevin Erdmann 00:50:09

Yeah. And then the worst part about that is that that risk will be very procyclical. They'll be throwing that at you at the worst point in the business cycle.

Shane Phillips 00:50:17

So thinking about alternative explanations here, I think a likely one you might hear is that what has caused this change in the distribution of who is getting a mortgage is less about lending standards and more about housing prices. So higher credit scores are correlated with higher incomes, though I looked this up and the association is weaker than you might expect. But there is an association there, and I would guess that people with lower credit scores are also less likely to own a home already, meaning they have less wealth through that channel, and may be just less wealthy generally. And most importantly, housing has gotten a lot more expensive over the years. So how do we know that this is not just a matter of— or at least primarily a matter of housing prices rising past a level that a lot of people who don't have great credit can afford. So they're not unable to buy a house because of their credit, but because of their income and wealth, which just happened to be correlated with credit.

Kevin Erdmann 00:51:15

Yeah, actually I think the answer to that question is really key to understanding all of this, because home prices are higher because rents are higher, and those families that you're talking about are spending more of their income on rent to stay in the same old houses than they used to. And I don't think there's a mechanism other than being locked outta mortgage access and not having enough homes that would lead people to, inflate the rents they're spending on the homes they're living in. I think the short answer to your question is that you take a typical house, somewhere in a random city in the country, that was renting for $1,000 a month in 2007... adjusted for inflation, rents on that house are probably up to say $1,400 a month by 2019. And we're probably taking a larger portion of that family's income to stay in that same house. That same house in 2007 was selling at a price that would require a mortgage payment of say, $1,200 a month, and by 2019 it had a mortgage payment of maybe $600 a month. So over that period of time, the rental versus ownership price of the homes that are on the margin where people were locked outta mortgages was much more favorable to owning than it was to renting.

Shane Phillips 00:52:29

Okay. So you're saying especially in that six-ish year period after 2008, if you could get a mortgage, in many markets, you were much better off owning. And so the fact that people did not do that is a pretty strong indication that they could not.

Kevin Erdmann 00:52:44

Yeah, yeah. And of course a lot of investors came into those markets and made a killing during those years.

Shane Phillips 00:52:49

Right. And I know that's something you've written a lot about and I think it's pretty persuasive... just this idea that the reason that private equity and these corporations and so forth came into certain markets is, of course they saw an opportunity, but the reason they saw an opportunity was because the people who normally would've bought those homes were no longer able to get mortgages and couldn't. And so they were able to kind of swoop in. Prices probably wouldn't have fallen far enough for it to be a worthwhile investment for them if those people could have gotten mortgages. But because they couldn't, it created this opening. And as prices have recovered, unsurprisingly, we've seen a lot of those same corporations and private equity disposing of their assets, selling them off and moving out of this market in many ways.

Kevin Erdmann 00:53:34

Yeah, you know, actually that's a very underappreciated aspect. There was a lot of transfer of homes from owner occupied to investor in that 2008 to 2015 period. And since then the number of single family homes that are rentals has actually been generally declining. We basically had the one-time shock where 10 or 15 million households that used to be able to get mortgages can't under the new standards, and that was sort of a one time shock to the number of home owning households in the country. And once we got outta that shock, we went back to an upward trend. Each year there's X number of new homeowner households and X number of new renter households, and homeowners have actually been buying all the new single family homes on net that are being built, and buying some of the existing homes that were rentals and turning them into owner occupied homes. Basically forcing renters to move into apartments. And for the most part, just cutting renter household formation by millions.

Shane Phillips 00:54:35

Okay, so let's just take it as a fact that it has gotten much harder for people with merely good credit to get a mortgage, and therefore buy a home. I think that's pretty well established. That clearly sucks for them, and I think it's also just stupid policy at some level because there's no indication that many— most of these people are risky borrowers. They're just being excluded because we're being overly cautious, essentially, because we're overcompensating for the looser lending standards that had been in place before the financial crisis. But let's say you don't care about those people. Maybe simply because they're not you, and you've got great credit. Or maybe you think this actually benefits you because it means less competition and possibly a lower price when it comes time for you to buy a home for yourself. Tell us why even a selfish person like that should care about the impact of these overly restrictive lending standards. Connect some of these dots for us and tell us what all this means for housing production and affordability.

Kevin Erdmann 00:55:36

So I think you have to get a bit into the weeds to answer this question, and in a way, the screw you, I got mine position is true. Ironically, the main effect of reduced mortgage access is higher rents. I liken home ownership to subsistence farming. Even if many farmers are consuming their own grain, they're still affecting supply and demand, and if more people go into farming, the price of bread will decline for the people who don't go into farming. And so, increasingly I've come to the view that the 2008 American housing market is really a massive disequilibrium — that by 2015 we were in a position where the mortgage crackdown had arbitrarily lowered price to rent ratios compared to 20th century norms. And so rents had to rise by 25% or so on average to get home prices in these low-end markets back up to where builders could build new homes equivalent to them at the same price. In 2005, we completed about 2 million homes, and by 2012 it was down to 600,000. And it was back up to about a million homes by 2015. And I think at that point we were basically back at capacity — that we had permanently hobbled the construction industry so that now instead of a normal cyclical recovery back to the old level, it was the slow grind of redeveloping capacity over time. So I think for the past decade, we basically have been a country that needs 2 million homes a year that was only capable of completing 1 million. And that's slowly been rising. We're up to about 1.6 million new homes this year. I think we're still below the sustainable amount that would be needed to meet just natural household formation. And economists would call that hysteresis, I think is how you pronounce it, which is just a fancy word that means whatever the market's capable of at a given moment is a product or the path that it took to get here. And so now we're in this new moment of slowly rebuilding capacity. And so as a result, rent s are elevated in a lot of markets just because of this temporary gap of reestablishing ourselves into a construction market that builds enough to accommodate natural household growth. And I would say probably, maybe as much as 40% of elevated home prices, on average, are due to this temporary gap of slowly regaining capacity. And if we don't do anything in the marketplace policy-wise, slowly over the next 10 or 15 years, we will finally get above sustainable capacity. Rents will start to moderate. Prices will start to moderate. But the thing is, if we don't change mortgage access, I think we need probably 15 million homes, at least, to reattain the long-term trend in household formation. If we don't change mortgage access, those 15 million extra units will have to be, on net, units owned by investors for renting households. And of course there's a lot of noise about banning large scale investors. And I think if we did ban large scale investors, we would slow that rise in construction and rents would keep rising, homelessness Homelessness would get worse. But even if we don't do that, even if we allow that rental market to grow, if we don't loosen mortgages again, what'll happen is we'll settle back down where the elevated land prices in all these cities that are capable of growing will correct back to a low level. Home prices will correct back to a level that's equivalent to buying a marginally valuable lot on the edge of town and whatever it costs to build a house on that lot. But rents will be permanently, on average, 25% higher than they were before 2008 because we have taken away so many potential suppliers in the form of former homeowners that can't be homeowners anymore. And so ironically, to get rents back down to the level they used to be actually requires healing the mortgage market.

Shane Phillips 00:59:26