An unequal burden: Lewis Center researchers document the disproportionate impact of auto debt

By JOEY WALDINGER

Many U.S. cities — including Los Angeles — grew alongside the automobile industry, resulting in a sprawling urban form most easily traversed by car. Today, cars are a practical necessity for most households, providing access to jobs, services and opportunities. In 2021, 92% of U.S. households owned at least one car, as did 78% of households living below the poverty line.

The ubiquity helps explain why auto debt is now the second largest source of consumer debt in the country.

Since 2020, a growing body of research from the Lewis Center and Institute of Transportation Studies has revealed how this debt falls unevenly across communities. Women and communities of color carry a disproportionate burden — inequities that have worsened since the pandemic.

Led by professor and Lewis Center director Evelyn Blumenberg, this research is attracting national attention, including invitations for Blumenberg to present to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis in October.

Research Highlights

Debt Burden from Automobile Loans Exacerbates Racial Inequality in California’s Communities

California is famed for its car culture and through the University of California Consumer Credit Panel (UC-CCP), researchers have access to detailed data tracking every car loan in the state.

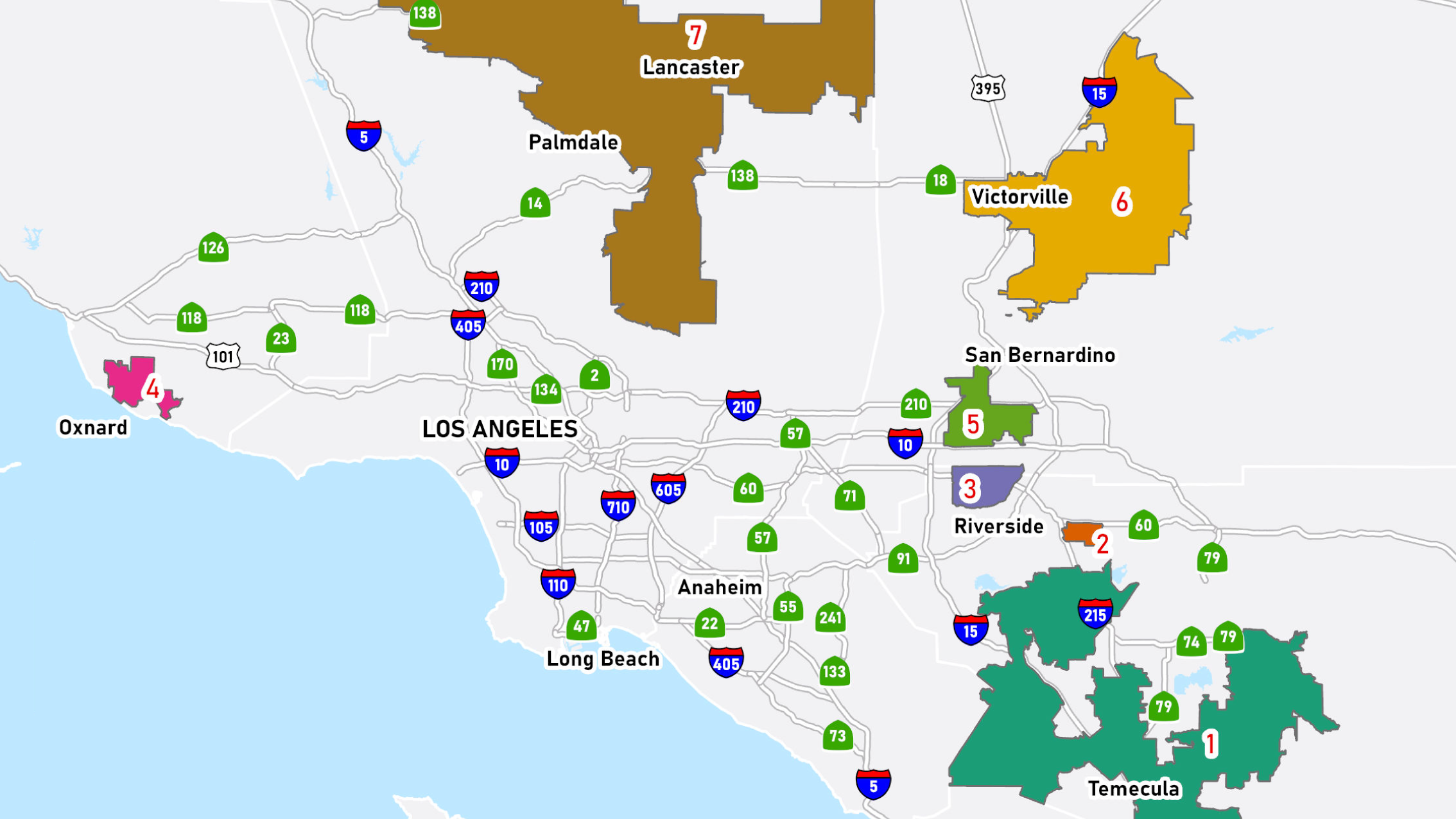

The UC-CCP database links loans to census tracts, allowing researchers to analyze neighborhood-level impacts of lending practices. Their findings suggest sharp racial and spatial divides:

- Black and Latino neighborhoods face higher debt per borrower and greater “automobile burdens” — the ratio of a person’s auto debt to income.

- Urban areas tend to have less debt per borrower than rural areas, but debt burdens are highest in heavily Latino regions such as southern Central Valley and Imperial County.

- Race and ethnicity are stronger predictors of auto debt levels than income, suggesting income-based policies alone will not reduce disparities.

“To reduce race-based disparities in loan costs, economic assistance must be coupled with fair lending rules and enforcement to combat discriminatory and predatory practices,” the researchers write.

Automobile Debt Increased Substantially during the Pandemic

As the COVID-19 pandemic upended lives and travel patterns, Lewis Center researchers returned to the UC-CCP dataset to examine how the pandemic affected auto debt.

After a brief dip in early 2020, auto debt rose dramatically from the second to third quarter of the year. The growth rate for new outstanding loans increased across all neighborhoods by race and ethnicity, but the steepest increases occurred in heavily Latino neighborhoods.

One explanation: Latinos were overrepresented among essential workers who needed cars to get to work. Stimulus checks may have also contributed, with research from the National Bureau of Economic Research showing that people with financial constraints spent more of their stimulus funds, including buying cars.

Driven to Debt: Social Reproduction and (Auto)Mobility in Los Angeles

Before the more data-intensive studies already mentioned, Blumenberg and co-authors examined auto debt through a theoretical lens, focusing on the rise of subprime lending in auto loans.

Drawing a parallel to the predatory practices that fueled the 2008 housing crisis and Great Recession, the paper explored how race, gender and class intersect with auto ownership and lending. By conducting qualitative research across L.A., including interviews with industry insiders and reviews of trade directories, the researchers found subprime auto lenders are operating on an increasingly large spatial and financial scale. By prioritizing volume over quality, low-income customers are often placed in expensive vehicles, with women and people of color targeted despite — and sometimes because of — their precarious financial situations.

Want to hear more? You can listen to a Streetsblog podcast episode where PhD candidate and research team member Sam Speroni discusses recent findings and what they mean for equity and transportation policy.