Episode 95: Low-Rise Multifamily with Tobias Peter

Episode Summary: Seattle’s low-rise multifamily zones have produced more than 20,000 townhomes over the past 30 years. Tobias Peter discusses the impacts on affordability, homeownership, and more — including lessons for other cities.

Abstract: We provide an in-depth case study of land use reforms in Seattle to highlight how redevelopment of aging single-family housing to townhomes can lead to a significant increase in market-rate housing that promotes affordability. The key is to allow market forces to use by-right zoning to drive small-scale development, when also supported by clear and simplified regulatory frameworks. We have dubbed this the Housing Abundance Success Sequence, which is supported by this study along with over two dozen others. In Seattle, we document that such policies lead to a sustained 2.5 % per year increase in the housing stock, with a range of about 1–2.5 % in other case studies. Importantly, this approach requires no government subsidies and leads to higher local tax revenues. Our findings underscore the potential of thoughtful land use reforms to create more inclusive, affordable, and resilient housing markets, while also demonstrating that inclusionary zoning mandates do not work and can stop market-rate developers in their tracks.

Show notes:

- Peter, T., Pinto, E., & Tracy, J. (2025). Low-Rise Multifamily and Housing Supply: A Case Study of Seattle. Journal of Housing Economics, 102082.

- The full catalog of AEI Housing Supply Case Studies.

- The Urban Institute study on upzoning effectiveness: Stacy, C., Davis, C., Freemark, Y. S., Lo, L., MacDonald, G., Zheng, V., & Pendall, R. (2023). Land-use reforms and housing costs: Does allowing for increased density lead to greater affordability? Urban Studies, 60(14), 2919-2940.

- AEI’s review and critique of the Urban Institute study: Peter, T., Tracy, J., & Pinto, E. (2024). Exposing Severe Methodological Gaps: A Critique of the Urban Institute’s Panel Study on Land Use Reforms. American Enterprise Institute.

- Episode 77 of UCLA Housing Voice: Upzoning with Strings Attached with Jacob Krimmel and Maxence Valentin.

- “This study, for the first time to our knowledge, using parcel-level shapefiles for Seattle from 1999 to 2025 provides an in-depth case study of Seattle’s upzoning of a relatively small area from single-family (SF) to low-rise multifamily (LRM) zoning in the 1990s. We document a sustained 2.5 % per year increase in the housing stock. We also analyze the price trajectories of single-family homes that were torn down and replaced with newly built townhomes, investigating how these SF-to-townhome (SF2TH) conversions have affected affordability in LRM zones and attracted a broader range of buyers. Additionally, we examine the profiles of builders engaged in these SF2TH conversions, their financing strategies and how the imposition of an inclusionary zoning mandate in 2019 influenced their decisions. We also compare home price trends between SF and LRM zones, finding no significant differences, and conduct an economic feasibility analysis to estimate the untapped potential for SF2TH conversions in Seattle’s single-family zones. This comprehensive approach sheds light on how zoning changes, informed by market principles, can influence developer behavior, housing affordability, and the buyer demographics across different zones.”

- “From this body of work, we have derived several generalizable insights. To have a significant impact, effective land use reforms should be straightforward and comply with the “keep is short and simple” (KISS) principle. The case studies identify a “success sequence” that if followed can have a meaningful impact of approximately 1–2.5 % in supply additions per year. The steps in this sequence are (1) enable by-right zoning, (2) allow greater density in many areas particularly those that are walkable and amenity-rich, and (3) implement short and simple land use rules, fast permitting and reasonable building standards without side constraints. We believe that without adhering to these principles, the efficacy of land use reforms is likely to be limited.”

- “Housing affordability is typically measured by comparing house prices/rents to area income. High ratios indicate an affordability problem and can reflect either issues in the local housing and/or the local labor market (Glaeser and Gyourko, 2003). If land values comprise a relatively large fraction of the total property value, this reflects issues in the housing market. On the other hand, if land values comprise a relatively normal fraction of the total property value, the high price/rent to income ratio reflects issues in the labor market. To identify markets with housing related problems, Glaeser and Gyourko (2003) estimate the cost of construction for properties and back out the land values from self-reported house values. They find that most housing markets do not have relatively high land shares. In their words, “The majority of homes in this country are priced—even in the midst of a so-called housing affordability crisis—close to construction costs. The value of land generally seems modest, probably 20 % or less of the value of the house.””

- “The case study approach focuses on the market response to implemented land use changes at fine levels of geography (preferably down to the parcel or lot level). This response is inextricably tied to two considerations. The first is a parcel’s highest and best use that is legal (HBU). The Appraisal Institute defines HBU as: “The reasonably probable and legal use of vacant land or an improved property that is physically possible, appropriately supported, and financially feasible and that results in the highest value.”4 The Appraisal Institute delineates four tests used in making this finding:

- Legally permissible: Which use cases are permissible by law, zoning and other land use regulations?

- Physically possible: Constructing buildings on the side of a mountain or in a swamp probably aren’t possible or cost effective.

- Financially feasible: Does the use case of the property suit the demographics and market of the area well?

- Maximally productive: Does the intended use optimize the potential of the land?”

- “The second consideration is that while land is considered to be permanent, structures suffer from depreciation and obsolescence. The process of land share increasing as an existing structure’s economic value declines leads to a desire by property owners to optimize the potential of land to the extent it is physically possible, financially feasible and legally permissible. That is, as single-family homes depreciate and are replaced, removing imposed land use restrictions and having governments step out of the way will allow redevelopment to take advantage of a parcel’s higher and better use, which usually means more density. This process, over time, has the best chance to increase the supply of housing in high priced markets by driving down the land premiums per square foot of living space and increasing affordability.”

- “Seattle’s first building code published in 1909 focused on construction and safety standards. This focus was an outgrowth of Seattle’s “great fire” in the Summer of 1889 that consumed over 100 acres of the city’s business district and waterfront. At this time, there were no zoning ordinances that focused on single-family housing.6 That is, low-rise multi-family housing could be built anywhere within the city.”

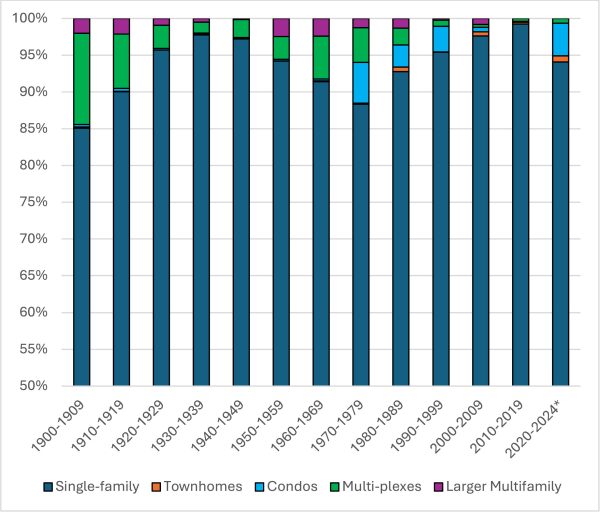

- “As a consequence, from the early 1900s up to the 1920s Seattle neighborhoods provided a mix of housing densities in close proximity. This is illustrated in Fig. 2. There was a marked decrease in the pace of multi-family housing construction in Seattle following the end of the Great Depression. This is illustrated in Fig. 3. At the same time, there was an acceleration in the pace of single-family housing construction. An important factor contributing to the relative shift to single-family construction was the adoption in 1923 of Seattle’s first zoning ordinance (Ordinance 45,382). The ordinance was designed by Harland Bartholomew and was based on his 1919 plan for St. Louis (see Bartholomew, 1919).”

Fig. 3. Existing housing stock in Today’s single-family zones: by decade built.

Note: The data are based on today’s tax assessor data, which means that homes that have been torn down are no longer counted. Source: City of seattle and AEI housing center.

- “One aim of Bartholomew’s zoning plan was to promote segregation of neighborhoods by income and consequently by race. Single-family housing is more land-intensive than multi-family housing which increases its relative cost and therefore makes it unaffordable for low- to moderate-income families. The zoning code was rewritten in 1957 adding new zoning classifications, downzoning many second residence districts, and designating even a greater percentage of the city to exclusively single-family detached homes.”

- “An implication of Seattle’s historical pattern of housing construction is that when we get to the mid-1990s and the GMA a significant faction of Seattle’s housing stock was aging single-family housing. This presented both a challenge and an opportunity in terms of how to design a plan to manage the city’s redevelopment and provide sufficient capacity of land for housing. The challenge was that, based on the principles of highest and best use (HBU), it is expensive to replace an aging single-family detached house with a new single-family detached house. If single-family detached (SFD) is the only permissible HBU and land is expensive, such parcels are effectively zoned only for conversion to larger, more expensive homes. This replacement process puts more upward pressure on house prices. The opportunity was that changing zoning at this time so that more of this aging single-family housing could be replaced with higher-density multi-family housing would improve the return for builders, supply more affordable housing to the market and relieve the excess housing demand due to population growth.”

- “The urban village concept was a core component of the new plan [the city’s 1994 comprehensive plan] … Urban Villages, as outlined in the plan, are designated areas where growth is concentrated to promote mixed-use development. These areas aim to combine residential, commercial and retail spaces, enhancing both walkability and transit use. Urban Villages incorporate a variety of housing types while also striving to create complete, self-sustained neighborhoods that include jobs, services and amenities within close proximity. Low-Rise Multifamily (LRM) Zones, created as part of the urban village strategy, are specific zoning classifications that allow for the development of lower-density multifamily housing, such as townhomes, duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings typically up to three stories.”

- “In the mid-2000s, Seattle streamlined the low-rise zoning categories, reducing them from four to three zones—LR1, LR2, and LR3—to simplify development regulations and encourage moderate density in appropriate areas. Within these LRM zones, the construction of townhomes, rowhouses, duplexes/triplexes and small apartment buildings is allowed “by-right”, meaning that developments conforming to zoning standards can proceed without needing special permissions or variances.”

- “The zoning laws in these areas define allowable Floor Area Ratios (FARs)—measures of a building’s floor space relative to its lot size. Per Krause (2015), allowable FARs typically range from 1.0 (LR1) to 1.4 (LR3).10After the 1994 reform, as illustrated in Fig. 4 approximately ten times as much land in Seattle was zoned for single-family as for low-rise multi-family.”

- “We examine the impact of Seattle’s zoning reforms on its Urban Village (UV) zones and Single-Family (SF) zones utilizing public records deed information and the most recent assessor data. The focus is on how the rezoning to LRM in UV zones led to significant increases in built density and housing supply. Over the same period, the SF zones, which were largely untouched by these reforms, remained static in terms of density and added little supply.”

- “Following the mid-1990s zoning changes, as shown in Fig. 6, UV zones saw a notable increase in housing density largely due to the introduction of LRM zoning which allowed for the construction of higher-density housing forms such as townhomes, duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes. This stands in contrast to the SF zones where the built density remained mostly unchanged as development continued to focus on single-family detached homes.”

- “The LRM zoning in Urban Villages triggered a construction boom that began in the mid-1990s and accelerated in the 2000s despite macroeconomic disruptions such as the Financial Crisis. This is shown in Fig. 7. Since 1994, we estimate that around 20,000 new townhome units have been built in Seattle’s LRM zones. At a rate of conversion of 4:1, private builders converted around 5000 single-family homes. Per current tax assessor data, there are about 15,000 SFs left in the LRM zones, which suggests that in 1994, there were about 20,000 SFs in these zones. This means that on average about 0.8 % of parcels have been converted each year from 1994 to 2024.13 This also renders a net increase in supply over these 30 years of 15,000 units from SF2TH conversions which translates into a rate of additional housing supply per year of at least about 2.5 %.”

- “Our methodology overlays parcel-level shapefiles for Seattle from 1999 and 2025, following the approach and data from Krause (2015). This allows us to link nearly 20,000 of today’s townhome parcels in the LRM zones —where parcel boundaries have changed— back to their original 4500 parcel numbers … This methodology enables us to track the number of subdivisions per parcel, as well as parcel sizes. We then combine these current parcel records with current public assessor data, which provides today’s buildings living area, the year the new structure was built, and with an Automated Valuation Model (AVM) from Dec. 2023, which values these parcels at this point.”

- “In a second step, we link public records of builder purchases of SF homes with subsequent sales of townhomes built on the same parcels by the same builder within 3 years of each other … Both steps combined allow us to identify about 2700 parcels with about 11,000 units, or over half of all SF2TH conversions.18 This methodology enables us to track critical variables: (1) the initial purchase price of the single-family home, which in the case of tear downs approximates the land value; (2) the number of new homes built on the same parcel and their price points; and (3) the builder’s name and financing details.”

- “In the third step, we use historical assessor data from 2003 (the earliest available) and combine it with the parcel-level change file described above. This “matching” allows us to compare key property characteristics between SF homes that were converted to townhomes (SF2TH) after 2003, and SF homes that remained unchanged in the LRM zones. We specifically compare differences in lot sizes, living areas, year built, and assessed values and if there were differences in the types of SF homes that were converted over time.”

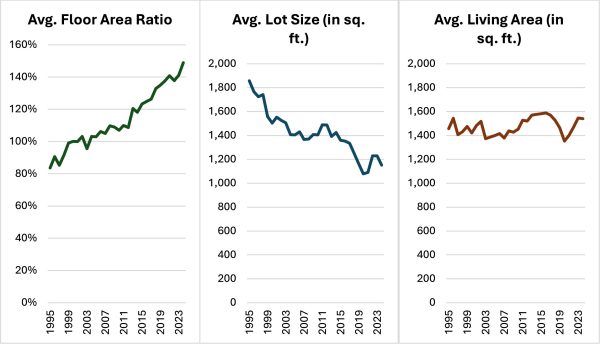

- “The number of townhomes built per parcel has averaged about 4.3 units per parcel, with a range between 3.1 to 5.1 depending on the year. The floor area ratio (FAR) has consistently increased from 84 % to the maximum allowable, as builders have adjusted to smaller lot sizes while maintaining an average living space of approximately 1500 square feet per unit with 2.7 bedrooms and 2.4 baths, as shown in Fig. 10. Based on the evolution of FAR in SF2TH conversions, low-rise multifamily zoning with up to 140 % FAR was sufficient in the 1990s and 2000s. However, developers are now consistently reaching the FAR ceiling, which indicates that the city should consider allowing even greater density in LRM zones and/or expanding LRM zoning to areas currently designated as single-family only.”

Fig. 10. Average floor area ratio, lot size, and living area for SF2TH Conversion by Year Built.

- “In regard to what parcels are converted earlier than others, Krause (2015) using data from 1999 to 2013 finds that redevelopment is most likely when zoning allows higher density and the existing structure is small, in poor condition, or on a large lot. Neighborhood characteristics like density, commercial proximity and recent redevelopment activity strongly influence redevelopment probability. Market conditions, particularly unexpected increases in home values, can trigger redevelopment decisions. This research reinforces that redevelopment is primarily driven by profitability and the highest and best use—higher potential income from new development versus the value of the current use.”

- “Holding the year of redevelopment constant, we find that for every additional 1000 square feet of lot size beyond 2500 square feet one additional unit is typically added to the redeveloped parcel. The average lot size for redevelopment was around 6000 square feet, but began declining in 2014 and has remained below 5000 square feet since 2019.21 Unlike lot size, we observe no clear trends in year built, gross living area, or assessed value among redeveloped properties. Developers appear to prioritize parcel size and, as noted by Krause (2015), prefer LRM2 and LRM3 zones where about 50 % of single-family parcels have converted since 2003, compared to only 30 % in LRM1 zones.”

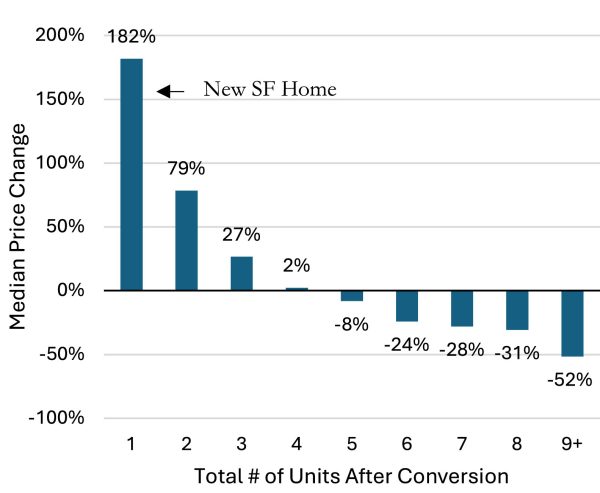

- “The implications of SF2TH conversion for affordability are substantial. Our data shows that higher-density conversions have a meaningful effect on housing prices as shown in Fig. 11. For example, when a single-family detached home is replaced by a new larger single-family home, the new home sells for approximately double the price of the original home. By contrast, if the same home is replaced by a four-unit townhome development, each unit sells for roughly the same price as the original home, effectively adding three additional affordable units. In cases where five to eight units are built on a parcel, the new units tend to sell at approximately 25 % below the price of the original home, significantly improving affordability. These findings suggest that SF2TH conversions can promote social inclusion and ultimately filtering down. Similar to Hamilton (2024), we find that large scale upzoning does not lead to worsening affordability. This is because SF2TH conversions – depending on density – are often just as affordable, if not more so, than the homes they replace.”

Fig. 11. Median price change between the unit replaced and the new units built.

- “We assess the current price points for single-family homes (SF) and townhomes built after 1985 in the tax assessor data, using an AVM from Dec. 2023, as shown in Fig. 12.23 The valuation of single-family homes in SF zones has nearly doubled, increasing from approximately $1 million for homes built in the 1990s to nearly $2 million today. This significant growth can be attributed to a substantial increase in the average living area of these homes, which grew from around 2200 square feet in the early 1990s to roughly 3200 square feet by the late 2010s, while lot sizes remained constant.”

- “In contrast, townhomes in LRM zones have maintained a more stable valuation, hovering around $800,000. This stability is partly due to the consistent size of these homes, which have maintained an average living area of 1500 square feet, even as their lot sizes shrank from approximately 1700 square feet in the 1990s to around 1100 square feet for homes built after 2019. For a household in the Seattle metro area with a 2024 median income of $158,700, this results in a price-to-income ratio of about 5 times for townhomes, but over 10 times for single-family homes.”

- “In SF zones where townhome construction is not permitted the prevalence of new single-family detached conversions to larger, more expensive homes is notable. Rather than utilizing the land for higher-density developments, developers in SF zones typically replace older single-family homes with larger, more expensive single-family homes. To counteract the resulting negative affordability effects, Seattle introduced floor-area-ratio (FAR) limits in these zones, but this regulatory effort has had limited success in addressing the underlying issues of affordability and density.”

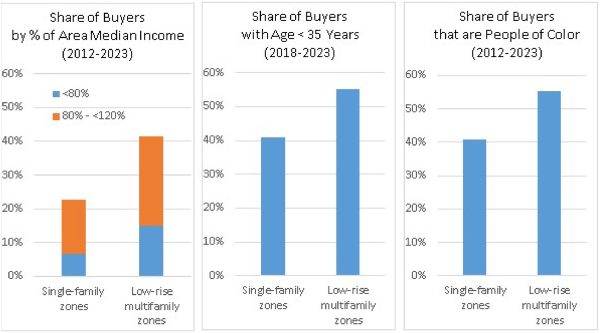

- “The proliferation of townhomes in LRM zones has had a democratizing effect on homeownership in Seattle. The lower prices and higher availability of townhomes have made homeownership more accessible to a diverse range of households, spanning various income levels, age groups and racial/ethnic backgrounds. By combining public deed transaction data with Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data from 2012 to 2023 (the match rate is around 50 %), we find that converting to higher densities enables families of similar or even somewhat lower incomes, younger ages, and more diverse backgrounds to buy into the neighborhood, thereby promoting inclusion as shown in Fig. 13.”

Fig. 13. Divergence in homebuyer characteristics.

- “The zoning change to the LRM zones has enabled (1) a more economically diverse group of buyers with a larger share of buyers below 120 % of area median income (AMI), (2) more younger buyers (<35 years old), and (3) a more diverse buyer population with fewer non-Hispanic white buyers compared to SF zones. These results highlight the greater diversity in terms of income, age and race in LRM zones compared to SF zones.”

- “Between 2012 and 2023, approximately 43,000 1–4 unit home sales occurred in LRM zones, compared to 67,000 in SF zones, despite differences in 1–4 unit housing stock (53,000 vs. 119,000).29 Most notably, townhomes built since 2000 in LRM zones were purchased by buyers with a median income of 133 % of AMI, compared to 230 % of AMI required to purchase single-family homes built since 2000 in SF zones.30 This disparity emphasizes the greater accessibility and affordability of townhomes in LRM zones.”

- “Seattle’s zoning reforms also fostered a surge in small-scale entrepreneurship. Our analysis of around 3500 infill property redevelopments between 1993 and 2024 shows that up to 1400 unique builders and developers were involved, with no single developer accounting for >2.5 % of the total volume—see Table 1.32 Interestingly, the nation’s largest builders, which typically focus on large-scale subdivisions, did not participate in Seattle’s infill development likely due to the small scale of these projects. Thus, infill SF2TH conversions helped to grow and sustain home construction with the work typically done by small local builders.”

- “We also analyze the rate of constant-quality home price appreciation (HPA) in the SF zones compared to the LRM zones. We implement a quasi-constant-quality methodology described in Davis et al. (2020), where we use an Automated Valuation Model (AVM) from Dec. 2023 as a “second sale.” This allows us to include in the estimation each property where we have an AVM rather than just properties that resold … We use public deed records data for Seattle going back to 1992. We limit the analysis to Seattle City and to 1–4 unit homes (single family, townhomes, condo, and 2–4-plexes).”

- “The results shown in Fig. 14 indicate little difference in the rate of home price appreciation between the two zones, with both experiencing similar growth until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Since then, there has been a slight divergence with larger single-family homes in SF zones appreciating more rapidly, likely reflecting changing household preferences during the pandemic for larger homes. This suggests that townhomes, despite being more affordable and higher in density, do not depress home price appreciation in surrounding neighborhoods.”

- “Despite these successes, the persistence of restrictive SF zoning across much of Seattle continues to limit the city’s ability to meet its growing housing needs. To ensure that Seattle’s housing market remains accessible and inclusive, policymakers could prioritize the expansion of LTD policies to additional areas still zoned exclusively for single-family homes. Allowing moderately higher density in walkable, amenity-rich areas currently zoned for SF housing could unleash a new wave of small-scale developers, replicating the success seen in the LRM zones.”

- “In 2019, Seattle passed the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program with the goal of creating thousands of new subsidized housing units made affordable through fees on development, while also boosting overall housing production. This new program is on track to destroy Seattle’s SF2TH conversion progress. Under MHA, builders have a choice between designating up to 11 % of units as income-restricted or paying a hefty fee.34 Based on a 2021 survey of trade group members of the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties, “the average MHA fee per townhome unit is $32,743, or $130,972 for an average four-unit project.””

- “These substantial fees effectively double the predevelopment costs for townhomes, discouraging their development. As a result, as shown in Fig. 16, new townhome permits in MHA areas have plummeted 80 %—from around 150 townhome permits per month to around 30—with the decline in townhome development occurring immediately after MHA’s imposition. In contrast, construction in SF zones, which are not subject to MHA requirements, has remained largely unchanged. It wasn’t until late 2022, with the onset of higher interest rates that construction slowed across the board.”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips.

This week, we're joined by Tobias Peter to talk about his team's research on the impacts of Seattle's low-rise multifamily zones on housing production, the price and affordability of new homes, the availability of more diverse family-sized housing options, home ownership, small business, and more. Seattle has had these low-rise zones surrounding its denser urban village areas since way back in 1994, and in that time, developers have built more than 20,000 homes. Most of those were townhouses, typically with about four townhomes replacing one single-family detached house. These zones have provided a steady source of relatively affordable new homes in the city, especially when compared to the much larger share of the city where multifamily housing is banned and older detached homes are often redeveloped into multimillion-dollar mansions. Similar to successes in Houston and Portland, this case study of Seattle shows the potential of reforms that encourage low-cost, light-to-moderate density housing options, and especially those that lower minimum lot sizes and make owner-occupied townhomes simple and easy to build. At the same time, it's also a cautionary tale about what can happen when you restrict these affordable options to too small an area or start adding costs and complexity to their development, both of which Seattle is guilty of, for which it is by no means unique.

The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Brett Berndt, and Tiffany Lieu. Send your questions and feedback to shanephillips@ucla.edu, and if you like the show, give us a five-star rating and a review on Apple or Spotify. With that, let's get to our conversation with Tobias Peter.

Shane Phillips 2:12

Tobias Peter is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the co-director of AEI's Housing Center, and he's here to share his research on the impact of Seattle's low-rise multifamily zones, adopted way back in 1994 with some streamlining updates in the years since. Tobias, thanks for joining us and welcome to the Housing Voice Podcast.

Tobias Peter

Yeah, thanks for having me.

Shane Phillips

And my co-host today is Mike Manville. Hey, Mike.

Michael Manville

Hey, great to be with both of you guys.

Shane Phillips

Tobias, we start every episode by asking our guests to give us a tour of a place that they have lived and want to share with our listeners. So be our guide. Where are you going to take us today?

Tobias Peter 2:50

Well, I'm going to take you to a very cold place, St. Cloud, Minnesota. It's a town of about 75,000 people, about an hour northwest of Minneapolis, St. Paul. And I got introduced to it as an exchange student in high school coming over from Germany. And despite the cold, or you may say because of the cold, the people there are actually really warm and friendly. And it has become my home away from home. And my love going back there, as you can imagine, people have very different perspectives as I'm here in DC. And we also implemented a sister city relationship between St. Cloud and my hometown in Germany. And we had many different delegations going back and forth, which has created lasting friendships. And it's been really a joy to watch the relationship between the cities, but also between individuals bloom. But there's also another reason why I want to talk about St. Cloud. And St. Cloud, when I came there many, many years ago, housing was not on anyone's radar. But that is changing now. But it also comes to show that even in a place like St. Cloud, Minnesota, it is possible to affect change. So just last year, because of leadership from the mayor and the council, they implemented an ADU ordinance, which now allows ADUs to be built in single-family zones, more or less by right. Now, not many ADUs are going to get built in the near term or even in the medium term, but the city is now, because of this change, it's now on the right trajectory.

Shane Phillips 4:24

I imagine that the climate is a little more similar in St. Cloud to where you're from than DC is.

Tobias Peter 4:31

Well, I mean, nothing really prepared me for St. Cloud, Minnesota. DC is very humid and hot, especially during the summer months. My hometown was just the happy medium, but somehow I had to get out. It's a very small town. And yeah, initially I thought St. Cloud was the big city, but of course, perception has changed.

Shane Phillips 4:56

Got it. All right. Well, this week we are talking about a study out this year in the Journal of Housing Economics titled Low-Rise Multifamily and Housing Supply, a case study of Seattle, also a much larger city than St. Cloud. Along with Tobias, Edward Pinto and Joseph Tracy co-authored this article, which provides an in-depth case study on land use reforms that in some parts of the city took land that previously only allowed detached single-family houses and rezoned it to allow townhomes and low-rise multifamily housing. Even having lived in Seattle for about six years, this is history I was only vaguely familiar with, and I think the research team here makes a strong case that these were important and impactful reforms with a lot of valuable lessons for other cities. They also bring data to some misleading but longstanding arguments against infill redevelopment, like the idea that new units are just as expensive, if not more so, than the homes that they replace. Spoiler alert, they are not. Because the fate of these older single-family homes often is not a choice between preservation or redevelopment into multifamily housing, but rather between redevelopment into multifamily housing or into a much bigger single-family home. I mentioned that this research is presented as a case study, and Tobias, you make a point of emphasizing the value of case studies early in the article. I tend to agree that they can be undervalued in academia and in the research community. And in the article, you say AEI has created over two dozen of these now. So I'd love to start by just hearing some of your reasons for why case studies have been a priority.

Tobias Peter 6:39

Yeah, excellent, excellent question. When it comes to up-zoning, we think you really need to understand the full context, especially at the local context. And what happened before and what happened after? What was up-zoned? How big of the area was up-zoned? How much up-zoning was done? Were there any poison pills left in place, for example, that even, despite the best intentions, could spoil any up-zoning? And with these case studies...

Shane Phillips

aAssuming the intentions were good.

Michael Manville 7:11

A well-intentioned poison pill.

Tobias Peter 7:14

Yes. Yep. And with these case studies, we like to go back many, many decades. Seattle is a good example of where we started in the mid 1990s, but we also have other case studies where these zoning changes occurred in as early as the 1930s. And some of them were not done deliberately. They just had a zoning quirk where they said, well, from this day on, we're going to define single family as one and two unit. Could be something as simple as that. And nothing really happened in that town until the 1990s, when land prices and land values started to increase. Just to give you one example, and Minneapolis certainly has been on everyone's mind in terms of up-zoning, and well-intentioned or ill-intentioned, Minneapolis, I'm sure you're very aware, did not increase the floor area ratios when they did away with single family zoning.

Shane Phillips 8:02

This is when they did away with single family zoning and allowed technically three units on any residential parcel. But yeah, they didn't allow you to build any bigger a building than the single family homes that you were previously allowed to build. So you had to divide it up in the same amount of space and other standards were kept the same as well, right?

Tobias Peter 8:21

Yeah, which made it nearly impossible for builders to build. So that's one reason why we like to look at case studies rather than just have machine learning scrape newspaper articles as others have done. But we also want to be very precise with this because the NIMBYs will latch onto anything that they can to really stifle any up-zoning. And Minneapolis is a great example that's often being thrown around. The other one is another think tank study where that happened to me where I said, well, up-zoning is great, it works. Well, look at this study by Urban Institute, which doesn't show that up-zoning really works. And hence the need for these very detailed case studies because they allow us to really understand what's going on.

Shane Phillips 9:06

and just to just to elaborate on that Urban Institute study the criticism there, they looked at a bunch of different up zoning policies to kind of see what the effect was, and they found a pretty limited effect, as my recollection more so, they found that down zoning had a negative effect, but up zoning didn't have much of a positive effect. But I think the criticism of that paper, which I do think still has some value, but, you know, a real flaw is they, you know, they kind of group together big up zones and small up zones. They don't account for up zones that were more kind of symbolic, like like Minneapolis is that have these poison pills versus ones that don't. And when you kind of put those all in the same bucket and do an analysis on them, unsurprisingly, it averages out to not much of an impact. But you know, if you look at the ones that maybe were the most effective, you might see much bigger effect. And those are the ones really we should be learning from, right?

Tobias Peter 10:00

Yes, exactly. And we've done a deep dive into the Urban Institute paper and we did a 20% random sample of all the newspaper articles that they analyzed and some of them really stated that this policy change only affected a small part of town or this was about a new subdivision that was granted to be built, which had 36 housing units in a town of 30,000 housing units. So the impact is always going to be muted, which is why we think that we really need to understand the context a little bit better.

Michael Manville 10:32

Yeah. I mean, I think we, in California, we have our own example of this, which is SB9, which if you read the newspaper or the media, it's like, oh, California has ended single-family zoning. But of course, the pill that was attached to that is that the owner, occupant has to be the developer, which of course just doesn't work for the vast majority of people who own single-family parcels. And so it really has not been used very much at all. But certainly a superficial look at that, you could say, California ended single-family zoning and it did nothing.

Shane Phillips 11:06

Yeah. Four homes on every parcel and yet nothing happened. What's the deal?

Michael Manville 11:11

And yet it happened because, oh, by the way, there's also a requirement that you, the owner, have to decide that whatever else you thought you were doing with your life, you're now a developer and no one wants to do that. That's not how we build housing.

Tobias Peter 11:21

Yes. It's these poison pills that really, the devil is in the details.

Michael Manville 11:26

Yeah, you're absolutely right. The devil is in the details and that is why, I mean, I'm as much of a fan as the next quantitative social scientist of a gigantic regression, but there are times when you really do have to know the minutia because when push comes to shove and things are working their way through a city hall or a state legislature, one or two small lines of law can change a statute from something that's incredibly effective to something that just kind of sits there on the books and no one can really take advantage of.

Shane Phillips 11:56

So getting into this case study, tell us about Seattle's low rise zoning categories and their origins. These zones have been around since 1994 and they allow what we think of today as missing middle housing. And actually since the mid-2000s, they've allowed many of these projects by right. Seattle strikes me somewhat as ahead of their time on this, both for the zoning reform itself and the ministerial, this non-discretionary approval process for projects.

Tobias Peter 12:23

Yes, that's absolutely true. But you could also argue that Seattle was ahead of its time or Seattle was ahead of getting back to what it used to be normal. And in the paper, we have a map where we show that prior to 1920, these missing middle or low rise multifamily light touch density, as we call it, duplexes, triplexes, quadruplexes, they were normal and they were interspersed pretty much through many, many neighborhoods in Seattle. And then in the 1920s, that was all made illegal because of the federal push to implement zoning policies.

Shane Phillips 12:59

That's something that's shared across most cities, but yeah, Seattle's unique or somewhat unique in having re-legalized them earlier than most places, in some places at least.

Tobias Peter 13:09

Yes. And the origin behind all this re-legalization was a state law that Washington passed in 1990 that really tried to focus the cities away from sprawl and towards more urban infill. And the city of Seattle got to work and then over a series of four years started to implement these low-rise multifamily zones. And it all started really with the concept of urban complete cities where you had access to jobs, to transit, to amenities, to services. And in these small zones, which actually only accounted for about 10% of the residential areas, this was all done because a political compromise, because the city figured if you do it across the board, we're getting too much pushback. So they did it only in these small residential areas and they allowed anywhere from 1.0 to 1.4 floor area ratio in these zones. They started with four low-rise multifamily zones, eventually they went back to three to simplify it a little bit. But with an average lot size in Seattle of about four to 5,000 square feet, with this law, you can actually build about four units by right on each parcel, which was the genius of this law.

Shane Phillips 14:21

Yeah. And today, one FAR to 1.4 FAR, which if you had a 10,000 square foot lot, that means 1.0 FAR means 10,000 square feet of building that you can build, 1.4 would be 14,000 square feet. So on a 5,000 square foot lot, cut that in half. Does that seem like a lot? Like a little? I'm just thinking about this in relationship to Portland's residential infill project that they approved a while back, which allows all kinds of missing middle housing in their single family zones. And theirs actually caps out at 1.0 FAR. It increases as you build more units. So it's something like if you only want to build a single family home, it's 0.6 FAR. If you want to build a duplex, it's 0.7 or 0.8. And if you go up to four, you get up to 1.0 FAR. Just curious if this is like a good amount, or maybe it's more of it was a reasonable amount in the 90s, but maybe is less so today.

Tobias Peter 15:17

Yeah, I think the data showed it was a very ambitious amount at the time it was passed. And we've looked at this too in one of the figures, where we look at the average floor area ratio of the new developments. And in the mid 1990s, it was about 80 to 100 FAR, 0.8 to 1.0. But it has certainly steadily increased its home prices and housing shortage in Seattle has grown. And today we're bumping up against that FAR limit, which goes to show that Seattle needs to do more. It needs to go higher. And 1.6, 1.8, it's certainly still feasible, but you cannot go much above it, as you said, if you have lots of 4,000 or 5,000 square feet. At some point, you need to go to four stories and that's not going to be feasible.

Shane Phillips 16:02

Okay. And so these projects are all limited to three stories or less. That's kind of the low rise part of this. Got it. So Seattle established these urban villages that entailed rezoning some single family zones. This wasn't all that happened, but part of what they did with these urban villages is rezone some single family zones to allow low rise multifamily, like these townhouses, two and three and four plexes, that kind of thing. Your study looks at the effects of that rezoning limited as it was in geographic scope to about 10% as much land as was zoned for single family only. Let's just start with the effect on housing construction overall. How many missing middle type homes have been built in these low rise zones since they were established back in 1994? And how does that compare to the single family zoned areas that continued prohibiting townhouses and multifamily?

Tobias Peter 16:55

Yeah. So it was, I mean, Seattle, even back in the mid 1990s, and correct me if I'm wrong here, but it was mostly built out. There was not that much vacant space available. So any development that occurred had to be to tear down an existing structure and replace it with a new one. And in the single family zones where you could only be building single family homes, there the conversion has been from older single family homes to McMansions. And that happened about the same rate as happened before. We have a chart in the paper where we look at the period before the zoning change was implemented. And basically what was being done before continued after the zoning change, except that because the housing shortage has grown higher, land values have gotten higher. These McMansions that were built started to get larger as well. On the other hand, in the low rise multifamily zones, there we see a building boom. And about 5,000 single family detached homes got torn down. And they built about 20,000 new units. So an average four unit per parcel or an additional 15,000 units that were being built. Over the last 30 years, that amounts to about an increase in housing supply of about two and a half percent in these small areas. And of course, had Seattle at some point in time expanded the low rise multifamily zones to additional areas, a lot more could have been built. And the housing shortage in Seattle would be less severe. Of course, could have, would have, should have, but it's still pretty significant what has happened over the time period.

Shane Phillips 18:29

And I noted in that chart you're referring to, it looked like the total amount of housing built in the low rise multifamily zones was closer to 25,000, 26,000 units. The 20,000 you just referred to are really the townhouse style, right? And so were the remaining five or 6,000 also mostly multifamily or were those the kind of one for one mansion replacing a single family home or a mix?

Tobias Peter 18:54

Yeah, I mean, some of it may be measurement error. We have different sources that we're using. So we're using kind of the data, the public records data, but then we're also using census ACS data to get estimates of the total number of units built on a housing stock. There can be some differences, but yeah, there could have been some duplexes, some plexus that could have been building these areas. Also some single family homes could have been built, right? But that's really an important piece here that if you give the developer to choice as this low rise multifamily zone has done, so you can certainly build single family homes or make mansions if you want to. But if you give the market a choice, the market has been building these townhomes because they are much, much easier to sell and developers can make a bigger profit by building four townhomes, selling them at a million each rather than building a one big mansion, selling it for two and a half million dollars.

Shane Phillips 19:46

So we haven't talked about your data sources for this study. You just mentioned one or two of them, but they include parcel level shape files for the city for 1999 and 2025. You've got assessor data for things like building size and year built and assessed values, and then public records on property sales. A lot of your findings focus on the characteristics of parcels and buildings in these low rise zones before and after redevelopment, and specifically on the redevelopment of single family houses into townhouses. I'm guessing that part of the reason you focus on townhouses is because they tend to be these subdivided parcels. And so each home has its own parcel and its own transaction history that you can follow. Those windows tend to be more complicated to track and get data on in my experience and rentals just aren't directly comparable to the earlier sale of a single family house. Feel free to correct my assumptions or add to those data notes, but those points aside, I think it'd be helpful to hear a little more about how the development process differs for townhouses compared to other projects like fourplexes and duplexes, and also how their different legal structure influences home ownership and the opportunity to buy. Because this also came up in our conversation with Nolan Gray talking about Houston and their small lot, their minimum lot size reform.

Tobias Peter 21:09

Yeah, I think a lot of it is revealed preferences because the vast majority of the new units that were built in Seattle were really, as you said, subdivided townhomes. And I think these are attractive from a developer's perspective. You can sell them individually, and also they are attractive from a buyer perspective because again, they are sold individually. So you only have to come up with $800,000 to finance versus if you want to buy a duplex, you need twice as much money and you need to be willing to become a landlord because you need to rent out the other unit. So I think for that reason, these townhomes are very, very attractive. And also as we've seen in Palisades Park, for example, where they're building duplexes, but they're selling them as condo units. But because they sold as condo units, you still have some sort of shared ownership and you have to pay a condo fee that then pays the insurance, the whatever. With the townhomes, it's much simpler.

Shane Phillips 22:08

Whether it's a duplex or a hundred unit building, you're now in an HOA if you're in a condo and there are costs to that, trade-offs, complications that some people just understandably... I think at some level, no one wants to do that. It's just like the price you pay sometimes to own a home in a dense city. But when these fee simple townhouse style developments are available, they do seem to have a lot of appeal. And I found the data that you dug up on owner occupancy really striking. You note that about three quarters of the townhouses built in these zones are owner occupied compared to 10% of the new multifamily in larger buildings in the city. You also make a good point about how these townhouses meet the needs of larger households. And I don't know if you say this in the article, but I think it's worth pointing out that they seem to be a more kind of market feasible means of providing those larger units. Whereas cities are always trying to kind of force developers into building three or four unit apartment buildings. And they don't have much luck because it's just like, it's not a very economical, financially feasible thing to do, but clearly in the case of townhouses, it works.

Tobias Peter 23:28

It surely does. And I mean, it's a great way to provide family sized units. So on average, these new townhomes are about 1400 square feet. So that's three bedrooms on average, two baths. And that's plenty for a young family with one or two children. We also looked at the large multifamily units that have been built in Seattle since 2000. And they've built a lot of large multifamily units as well. They were concentrated closer to downtown. And because they are closer in areas where we have high land values, they were also, and they are being built as high rise, which is more expensive to build. They were on average, they were much more expensive on a per bedroom basis than these townhomes. And on average, they had only one bedroom. So those were attractive for, and I think back to myself when I was 10 years younger, when I was still going out a lot and enjoying the nightlife, but now that I've settled down to have a family, I much appreciate my space and I really much like that my daughter sleeps in her own room.

Shane Phillips 24:32

So as I mentioned, you've got all this data on single family to townhouse redevelopment projects. Maybe you look at average floor area ratio, lot size, and unit size of these new homes. We got into this a little bit talking about how the restrictions or the zoning has become more of a binding constraint over time, but tell us how the characteristics of these projects have changed over time as Seattle has evolved and the prices have increased and what you make of those changes.

Tobias Peter 25:02

Yeah, so there have been some interesting changes or not changes. I mean, the average living area of these townhomes has roughly stayed constant between 1400 to 1600 square feet. That's quite remarkable. What has changed are that the lot sizes have become a lot smaller. So back in the mid 1990s, the average lot size on these townhomes was about 1800 square feet. Today, that's down to 1,000, 1,200 square feet. And because of that reduction in the lot size, the floor area ratio has increased from, as we talked about earlier, from 0.8 to about 1.4. So that's really a big change. But if you look at an automated valuation model of the townhomes that have been built since the mid 1990s, we find that the price today of these townhouse units has stayed remarkably constant at about $800,000. On the other hand, if you look at single family homes in the single family zones, newly built units, their price has increased from about a million to about 1.8 million. So those units have become much, much more expensive because the lot size has stayed the same. You have not been able to divide the lot size and because you have not been able to divide the lot size, you also need to build a larger housing unit. And those are your McMansions that are now 3,000, 4,000 square feet and that are becoming very, very, very expensive. And they are just replacing an affordable unit, putting home ownership further out of reach versus, you know, the other route is to allow more townhomes where you tear down an existing structure and you build four units on the same parcel that each sell for about $800,000.

Michael Manville 26:38

And then to make sure I understand the dynamic you're describing here, what's happened over time with the townhouses is that where in the past a developer might have divvied up the lot so that each townhouse sat on a slightly larger amount of land, now they're doing it with a smaller amount, just kind of recognizing that they need to be a little bit more economical with the land to maintain that price point. Is that a fair summary?

Tobias Peter 27:02

I think that's a fair summary and yeah, they just become more effective with the land that they're using.

Michael Manville 27:08

Yeah. And that makes a lot of sense and it also is something that, you know, it works for the developer, giving the developer that flexibility. You have the ability to look at who you want to target as the consumer and know what kind of price you want to hit. And then if you can adjust that on the land side, you can account for that.

Tobias Peter 27:27

Land is costly. Yes. Just by making the lot size a little bit smaller, you can reduce the price point.

Michael Manville 27:34

Yeah. It's an interesting finding.

Shane Phillips 27:36

And I imagine that there are still some cases where a developer is building these townhomes on 1600 or 1800 square feet. And so it's not as though that option is foreclosed. If a developer feels like there's a market for that, they'll probably still build it. But I suspect that most of the people in the market for a townhome would rather the 1200 square foot lot and an $800,000 townhome than, you know, an extra 400 square feet of parcel area and spend, you know, $1.1 million or something. That's probably just not a great value for people.

Michael Manville 28:13

It's a lot of money for a little bit of extra yard. Yeah.

Tobias Peter 28:15

Yeah. Well, in fact, it may actually include a disamenity if you have to mow the lawn, right?

Michael Manville 28:21

That's true. I do not like mowing the lawn, so.

Shane Phillips 28:26

And your data also can tell us which kinds of parcels are likely to be converted first. I don't think the results were surprising here, but I do think they're worth sharing since they conform with theory and prior evidence on what makes for an effective zoning reform. What did you find there?

Tobias Peter 28:43

Yeah. So these results are actually taken from a paper that Andy Krause did during his doctoral dissertation. And he was also kind enough to share the shape files from 1999 with us. But his findings were that, you know, kind of it starts with smaller lots of units that are in houses that are in poorer condition and particularly larger lots are more attractive to developers. So that's where it starts with. And that's certainly something that we've also found in our other case studies. It's always that these developers start with the older buildings that are in rough shape. They tear them down and then they move on to the next one. And that's exactly, I spoke to a developer in Palisades Park who has confirmed this. And he also added an interesting detail to this. He said these older homes that we are tearing down, once you take everything out, once you strip the home of everything, sometimes if you just kind of lean against the wall, the walls start shaking. And it kind of goes to show that, you know, it's also a little bit of a health and safety aspect to this. If we can replace our aging housing stock with state of the art, you know, energy efficient, new townhomes in areas that already have the infrastructure in place.

Shane Phillips 29:53

Sticking on this topic of land values a little bit, early in the article, you summarize some previous literature in a way that I thought was pretty memorable. What you said was something along the lines of when land values comprise a large share of total property values and the price to income ratio in a metro area or city is high, that reflects a problem in the housing market. However, when the price to income ratio is high, but the land share of property values is normal, say around 10 or 20 percent of total property value, that reflects problems in the labor market. This point about high land values being a problem is important, I think. So I wonder if you could say more about why it signals that a property is not being built to its highest and best use and how it often signals a zoning problem specifically when land values are a large share of property values across a housing market, not just on individual parcels here and there. And Mike, feel free to chime in on this because I know this is really your wheelhouse too.

Tobias Peter 30:54

If you think about the package of a structure and land, the structure tends to depreciate or if anything, it appreciates at the rate of inflation versus the land piece is really the one that fluctuates a lot. And if property values kind of double in price, it's not that the structure has all the sudden become more valuable, it's that the land has become more valuable. And these land share signal that the land is underutilized and it should be used differently at a high and better use. And we actually in our research, we're using these land shares quite extensively to estimate housing shortages, but also estimate just the conversion potential if other cities were to implement similar similar reforms as Seattle has done. So the higher the land share, the higher the land share is, the greater the need for redevelopment. And it's not that the market will stay frozen in place, it's that the market finds a way to return these land shares to a more normal level. If you have land shares above 80, 90%, the structure becomes very attractive to be torn down. It's just a question of what will replace it. If you leave the zoning in place, well, you're going to get a McMansion, you know, with all the negative effects that we talked about that it's going to be that you're removing a relatively affordable unit from the market and replacing it is a very, very expensive one. On the other hand, if you allow two, three, four units to be put in its place, you can keep the price point relatively similar. And then of course you can open up home ownership opportunities for people of more moderate means.

Michael Manville 32:24

Yeah. I mean, I think that summarizes it perfectly. One thing, you know, sometimes in class or whatever, we talk about the difference between, you know, places that both have affordability problems and you can imagine, you know, there's a lot of people in Detroit at its lowest part who have a hard time affording housing. And then of course, San Francisco Bay area. And both of these places have a lot of housing units that are bought and torn down, right? But in Detroit, you know, this is because the housing unit really is just sort of, it's better to have the land vacant. You know, it's sort of, it's oftentimes, especially when the city was really in its doldrums, just close to a worthless piece of property. Whereas in Palo Alto, someone buys a house and to tear it down, but they pay $2 million to do it. And it really captures, I think what you said in the article that on the one hand, you have a situation where people just have extremely low incomes. And so even if the housing is very, very cheap, they have a hard time affording it. And that's a labor market problem or a social safety net problem or however you want to put it. Whereas, you know, over here in coastal California, we have a situation where even people who make a lot of money by any objective measure have a hard time affording housing. And again, it's not because the structures are expensive, it's because our land is so expensive. And yeah, what you would expect in that situation in an unconstrained market is, and at least some of the time developers saying like, oh, I can buy this land and put 10 units of housing on it. And when that consistently doesn't happen, you know, to sort of loop all the way back to Shane's question, you start to look for a culprit. You know, what stops someone from doing what we normally do with a resource when it becomes very expensive, which is figure out a way to sell it in a smaller quantity? What stops us from dividing up land? And usually that answer really is the zoning laws.

Shane Phillips 34:12

Either sell it in a smaller quantity or effectively do that, but share it, you know, in the case of like a rental building where you're not selling individual portions of it, but yeah, you're dividing up the use of that land between many more people. So each person pays a smaller share.

Michael Manville 34:28

Yeah, yeah. It may not be an ownership sale, but whoever owns it does in fact have a commodity that they sell in a smaller quality, right? It might just be a 800 square foot apartment or something, but yeah, exactly.

Shane Phillips 34:39

To kind of tie together some of these concepts, you know, if there's one thing in this article that made me want to have it on the podcast, it was probably this analysis of how home prices changed after redevelopment. Anyone who has called for reforms to build more housing, I think especially in single family neighborhoods, has heard something along the lines of these new homes aren't even affordable. You're just tearing down relatively affordable old homes and replacing them with big expensive new houses. For the moment, let's just put aside the fact that there's still an affordability benefit to replacing one house with four, even if the four new homes are just as expensive as the old one. And there's an improvement to housing quality, which we talked about, an environmental benefit to increase density, all those things, that's all true. But ignoring all that, you really helped show that this argument is wrong on its own terms. And the reason is that it mistakenly assumes the original home would stay old and affordable if not for being redeveloped into townhouses or some other higher density use. The reality, which I think anyone who's lived in a city with high demand and too little new supply is pretty familiar with, is that the homes are often redeveloped either way. The question is not whether they're redeveloped, but whether they're redeveloped into a much more expensive mansion or into multiple less expensive homes. People like me and Mike and many others have been making this point for years, but you actually put some numbers to it and I found them really compelling. So tell us what you found there.

Tobias Peter 36:12

Yeah, thank you. Thanks, Shane. That was not an easy part of the analysis, but we did it by brute force. And the way we did it was that we've looked at single-family homes in these low-rise multi-family zones that were purchased by a developer. So that had an LLC in the name, or just even if it wasn't a developer, if it was an individual who then later within a year or two sold multiple units on that same street. We then compared the price of the original unit that they presumably purchased and tore down to the units that they sold on that same parcel. And what we found was that if they built a new single-family detached home, so a McMansion, the price point, the ratio between the original and the new home was about, it was 180% more expensive. So a million dollar home became a $2.8 million home. But there was a clear gradient to it. If you build two units on that same parcel, the price point dropped. It was still more expensive, but it was in quotes only 79% more expensive than the original home that was torn down. At three units, it was only moderately more expensive. At four units, it was about the same. So original home purchased for 800,000 units was sold for four units, each selling at $800,000. So that opened up opportunities for three additional home buyers and for people that had roughly the same income as the people that currently live there in the original home. But then if you increase the density even more, the five, six, seven, eight units, which in Seattle, the parcels are generally smaller. To get to eight units, you need a parcel of at least 8,000, 9,000 square feet. So they're a little bit harder to find. But if you sold eight units on that same parcel, the price point was actually 30% lower than the original home that the developer purchased. So it goes to show that if you use the land more effectively and if you have economies of scale, you can actually reduce the price point of new housing relative to the one that you're tearing down. And compared to a McMansion, this is certainly much preferable outcome. But that's not all. It's not just about the buyer. It's also about the developer. The developers we talked about before can make a higher profit, but also the city can realize a profit by gaining additional property tax revenue. If you have now eight units on that same parcel that used to be worth a million dollars that are now selling for 5.6 million, you can have a lot more property value that you can tax. And in Palisades Park, where we also studied this in great detail, Palisades Park in New Jersey, of all the boroughs in the area, Palisades Park used to have the highest property tax rates of them. But because of this building boom and this conversion to duplexes that has ensued, Palisades Park was able to lower its property tax rate and return some of the money back to the citizens and kind of publicize that to build some goodwill amongst the population that it's actually in their interest to support upzoning reforms.

Shane Phillips 39:20

Yeah. And I think this is just really important, both for showing the more units you're allowing on these parcels. And this is partly just a function of the parcel size, but also a higher density limit or FAR limit would also get you in the same place. The more you're allowing to replace a single family home, the lower the cost of each unit. And that's maybe somewhat obvious, not to everyone, but to many people. But I think that comparison to... You're kind of measuring the counterfactual as well when you look at the redevelopment when it is just another single family home and going from roughly a million dollar property to a $2.8 million, if it was a million dollars to begin with.

Michael Manville 40:05

Yeah. The thing to emphasize is that there's a very intuitive reaction people have that's understandable, which is in the event, say someone built the three homes, right? And so they were modestly more expensive than the home that it had been replaced. The intuitive reaction, particularly of someone who's skeptical is to say, oh my gosh, we had this one cheap house and now the new ones are more expensive. And even setting aside the fact that more people get housing and that it's brand new and all this stuff, when you adjust it for quality, it's probably cheaper and so forth. There's also just that comparison isn't quite right. I think it's just worth reiterating that because if you have a situation where an investor is looking to come into a neighborhood and create a newer, more expensive kind of house or a newer, more profitable kind of house and you outlaw building two, building three, building four units, then you're going to get the McMansion. So the real counterfactual is comparing what got built to the profit maximizing version of the single family home, which as we all know in Los Angeles is the gigantic house designed in about 11 seconds on Google SketchUp to occupy as much of the parcel as possible, in addition to being very expensive, all the neighbors hate because they think it's ugly. People look at these neighborhoods and they say, we don't want them despoiled by townhouses. And then you come back in a month and there's this huge ugly box that is the size of an apartment building that's a single family home. And it's just like, well, look, you got the building you didn't want and it's more expensive and you probably have some obnoxious dude in it with four Teslas instead of like a couple families. So, you know, who wins here? I do think it's just a really important takeaway from this paper is to put some numbers on this dynamic that I think a lot of us have seen play out kind of anecdotally.

Shane Phillips 41:58

I want to follow up on this because I think an argument you might hear in response to these findings is that you're comparing these single family home redevelopments, whether it's a one for one or a one to four, but it's possible that a lot of single family homes would be purchased by people who don't intend to replace them if you didn't allow four units on a parcel, for example. So I think the thinking here would go, sure, if someone buys a single family home and replaces it, then that home is going to be more expensive than if it were replaced by three units. But your data show that duplexes and triplexes are still more expensive per unit than the original home. And most people who buy single family homes don't tear them down and build new ones. So I think the response here actually goes back to the previous question about the parcels that developers target for redevelopment, right? They go for these sites with older, smaller, more rundown homes on larger lots. And these are going to be exactly the same parcels that a person just looking to build a mansion is also going to prioritize because they don't want to buy a recently renovated home and tear it down to redevelop it. I think this point is just really important as well, because it seems very easy to just argue, you know, sure, when you're comparing one for one to one to four, that's going to look favorable for replacing it with four units. But I think the point here is that the fate of parcels like these is redevelopment, gut renovation, it's something that is going to drastically change it, whether it is a new single family home, an old single family home, or multifamily, it's going to change and go up in value a lot after someone buys it regardless.

Tobias Peter 43:46

Yeah, I mean, I think my preferred solution would be just let the market figure this out, right? What is, what does the market want? What does the market need? And absent of zoning, certainly more housing units would get converted from a single family or the detached to more townhomes. But it also be that, you know, single family homes could get rehabbed and that's not precluding any of that, or that they get converted to McMansions, there's nothing stopping that. It's just that, you know, kind of, as Mike said earlier, if you can build the obscene McMansions of 5,000 square feet, why can you not build, you know, three or four townhomes at 1,400 square feet on that same, on that same lot, right?

Michael Manville 44:25

Yeah. And Shane, I think what you're saying in your remark before is basically that the limited magnitude of redevelopment that we see in most cities right now suggests that like there's selection bias in the parcels that do get redeveloped. And so someone might think it's a counter argument to say, oh, well, most people who buy a single family home, they don't tear it down and convert it into something. What that should tell you is, oh, well, there might be something kind of different about the parcels that do get bought and redeveloped, right? Like you said, they're run down, they're sort of, they're low value and they're just sort of, they're the kind of thing a developer would be very attracted to and a potential owner occupant would be less attracted to precisely because of the amount of investment that would be required. And it's those, when you focus in on those and you say like, well, what is the fate of a parcel like this, redevelopment one way or the other becomes much more likely and then you are back to this, well, do we want it to be the giant mansion or, you know, three or four units? And I completely agree with Tobias. I mean, it's, that's up to the owner, but the owner should at least have the option of doing three or four or five units.

Shane Phillips 45:35

Yeah. Tobias, another way you illustrate the relative affordability of these town home replacements is by tracking how property values have changed over time for single family houses in single family zones compared to town homes in the low rise zones. So tell us what you found there and again, how you interpret it, but maybe even before that you can explain how you estimated home values for this part of the analysis and share any warnings about the accuracy of those estimates because I know it's, you're not using sale prices. So it's, it's somewhat different than the previous analysis.

Tobias Peter 46:08

Yeah. So we are using what we call a quasi constant quality index and with a traditional constant quality, you know, repeat sale model, you have the same home selling once and then selling again the second time in the future. With our analysis, we are still using an actual sale price of a home, but then as the second sale to complete the sale pair, we're using an automated valuation model at a given point in time. So we're creating an artificial sale pair where one sale is an actual transaction and the second one is we're using an automated valuation model to value that home today.

Shane Phillips 46:48

And this is just because there's, you know, not many homes that sell twice in a, let's say 10 year period. And so you're really limiting yourself and what you can look at if you're only going with the repeat sales.

Tobias Peter 47:00

Exactly. It increases the n-count and also with these townhomes, right? Since a lot of the single family detached housing units get torn down into the place with townhomes, it is much harder to create a repeat sale index just because the quality of the homes has changed so much. Yeah. So, so we're using this quasi constant quality index and what we're finding is that the home price appreciation to two zones has been virtually identical. So for homeowners that oftentimes are afraid that, you know, allowing the neighborhood to be up zone, but it's going to crash their property values. It's simply not true as we find here. And we've done a similar study in Charlotte where we found the same, the same thing. It's just home values appreciated roughly the same, the same clip in either zone. And it's probably because people kind of, it's, it's still one market. And despite having different preferences on the margin, right, people kind of switch back and forth. But there are also some, some amenities that come along with the development is, you know, kind of, we've talked about the disadvantages of what traffic and more noise potentially, but they also, you know, kind of may perhaps the quality of the restaurants will increase or newness restaurants come in and crime may go down because you have more eyeballs, more eyeballs in the street. So all that is really hard to tease out, but, you know, the NIMBY concern is often that my property value is going to crater and we can, I think, pretty conclusively say this is not the case.

Shane Phillips 48:27

Yeah. And that seems really important.

Michael Manville 48:28

And of course it's always difficult to reconcile the often simultaneous objections of you aren't making the housing any more affordable and you're cratering my property values. It's sort of, you got to, you got to pick one.

Shane Phillips 48:44

No, I want both. I want my home value to keep going up, but I want all other housing to be more affordable for other people. Is that so much to ask? Coming back to this issue of the price of housing before and after redevelopment, one way of improving affordability is by allowing property owners to redevelop their houses into three or five or eight houses because when those options are available, then few will probably choose to replace their home just one for one with a mansion. Another option is just to prevent property owners from building these replacement mansions in the first place, which you write that Seattle also did in its single family zones in 2019, but that it had limited success. Could you elaborate on that a little bit? I think for the skeptics out there, you know, why not just pass an anti-mansionization ordinance and then focus new development in these taller, higher density projects in multifamily and commercial zones? That's basically been LA's approach over the past decade for the record.

Tobias Peter 49:42

Yeah, that's a great question. And I think with the anti-mansionization laws, I think in Seattle, it has had some success, but at the same time, people are finding ways around. And there are ways of, I think if you kind of basements, for example, can be excluded from the calculation. I have to go back and look at this. I mean, this was all based on a newspaper article that we found. There's ways for people to get around of it. But if you completely stop development, if you freeze everything in place, you also need to be careful that kind of the housing stock is going to age, deteriorate. And we've certainly seen that in Palisades Park when I talked to the developer who said some of these old housing units, they are not for people to live in. So I think that we should just rather than freezing everything in place, we should allow moderate up-zoning in these areas where it's feasible. I mean, the argument against putting all eggs in the kind of high-rise multifamily basket as Los Angeles has done, is to the extent that we want to promote home ownership as a society. And that's something that certainly politicians care a lot about. If you show in the paper in Seattle, the large multifamily units have a home ownership rate of less than 10% versus the townhomes have one of about plus minus 70%. And to the extent if you care about home ownership and wealth building, getting people into housing, that certainly seems to be the middle ground. It's not to say that we should not be doing high-rise multifamily, of course we should be doing it, but we should be complementing it with these family-sized units that allow people to get on the home ownership ladder.

Michael Manville 51:17