Los Angeles’s “mansion tax” has raised less money for affordable housing than expected. Lewis Center researchers explain why.

By JOEY WALDINGER

If you follow Los Angeles housing policy, you’ve likely seen recent headlines about Measure ULA. This initiative taxes real estate sales above $5 million to fund affordable housing.

Through December 2024, the measure raised roughly $480 million. That’s a sizable sum, but lower than expected. When Measure ULA was on the ballot in 2022, proponents estimated it would generate between $600 million and $1.1 billion annually.

So why has the tax underperformed? Lewis Center researchers are leading the charge to find out, publishing research papers and explaining their findings and recommendations through research talks and op-eds.

“Los Angeles needs housing and economic policies that work — especially as we recover from the January wildfires. That means balancing the urgent need for new revenue with policies that encourage new housing and jobs,” wrote Jason Ward, Shane Philips and Michael Manville in the Los Angeles Times. “Measure ULA, as currently structured, makes that balance harder to achieve.”

Approved by voters in November 2022 and enacted in April 2023, Measure ULA imposes a 4% tax on sales between $5 million and $10 million, and a 5.5% tax on sales above $10 million. Despite being billed as a “mansion tax,” however, ULA applies to all real estate transactions.

The result, according to new research, is that Measure ULA appears to drive down housing and commercial property development, and does not generate enough revenue to make up for the lack of production.

In their report, “Taxing Tomorrow: Measure ULA’s Impact on Multifamily Housing and Potential Reforms,” Phillips and Ward assess the measure’s effect on sales of land zoned for multifamily housing, a strong indicator of future development.

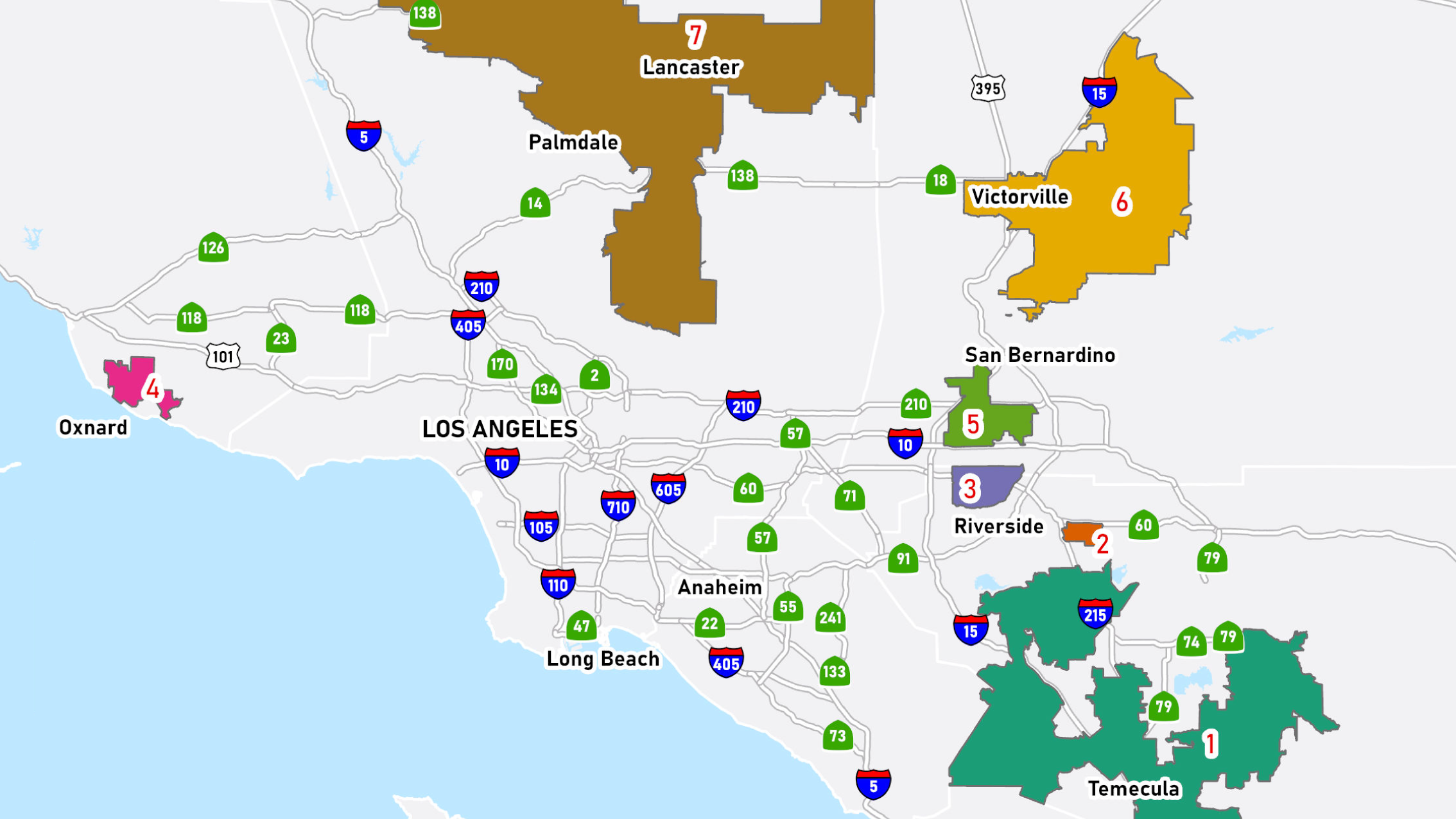

Using data of L.A. County real estate transactions between July 2020 and March 2025, they analyzed post-Measure ULA trends between the City of Los Angeles and other cities in the county.

Since the tax came into effect, sales of parcels with high redevelopment potential have dropped by half. Multifamily property sales, meanwhile, account for a small portion – less than10% – of ULA revenue annually.

In a separate report, Manville and Mott Smith, adjunct professor at USC Price School of Public Policy, examined the measure’s impacts on a broader range of property transactions. They analyzed four years of L.A. real estate data, finding that ULA appears to have prompted a 30–50% decrease in commercial, industrial, and multifamily property transactions.

Additionally, they found, the measure cuts in half the likelihood that a property will sell above the $5 million threshold.

Altogether, these results imply a tax revenue loss of roughly $25 million a year that will be compounded without reforms. Fortunately, the researchers suggest ways to reform ULA through simple amendments that still retain the measure’s original intent.

As they write in the Times piece, “It [Measure ULA] could become a better tool — one that fulfills voters’ hopes for more affordable housing, strengthens the local economy and protects the social and fiscal foundation of the region.”

Want to learn more about Measure ULA and how reforms could improve its outcomes?

And if you want a primer on transfer taxes:

Photo by Juan Carlos Becerra on Unsplash