Episode 32: Chile’s “Enabling Markets” Policy with Diego Gil

Episode Summary: Starting in the 1970s, the Pinochet dictatorship overhauled its housing policies in an effort “to transform Chile from a nation of proletarios (proletarians) to one of propietarios (property owners).” To achieve that goal, and others, Chile adopted what the World Bank would later call an “enabling markets” policy — an approach that reduced the role of government in housing provision and delegated more authority to the private sector. These reforms had far-reaching consequences, not only within Chile but beyond its borders as other nations followed its lead. Diego Gil joins us to share the history of the enabling markets approach and its impacts, both positive and negative. On the one hand, the reforms led to an impressive expansion of the formal housing sector. On the other hand, homes for low-income households were often built in poorly located, inaccessible areas. We explore the difficult task of balancing government regulation and market efficiency, the need for policies that address housing supply and housing demand, and Gil’s proposed alternative to the enabling markets policy.

- Mc Cawley, D. G. (2019). Law and Inclusive urban development: lessons from Chile’s enabling markets housing policy regime. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 67(3), 587-636.

- Machuca (movie).

- World Bank report: Housing: Enabling Markets to Work, 1993.

- Turner, J.F.C. (1976). Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments.

- Abrams, C. (1966). Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World. MIT Press.

- Hernando De Soto: The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World, 1989.

- Planet Money podcast episodes about the Chicago Boys: Part 1, Part 2.

- More on measuring housing needs/deficits in the U.S. context: Housing Voice episode 13 with Nick Marantz and Echo Zheng.

- Kuai, Y. (2021). Flying Under the Radar: 4% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program (Doctoral dissertation, UCLA).

- Celhay, P. A., & Gil, D. (2020). The function and credibility of urban slums: Evidence on informal settlements and affordable housing in Chile. Cities, 99, 102605.

- “In many cities around the world, the informal sector provides more than 50% of housing for urban residents. Many of these informal neighborhoods are home for large communities of disadvantaged and minority populations, in substandard housing, often occupying a piece of land without any formal title and lacking minimum basic services. Therefore, one of the most pressing policy challenges that governments confront today is how to accommodate all the people that need adequate housing in urban areas … “adequate housing” encompasses more than a habitable physical space, and includes “adequacy” in terms of location, transportation, and social integration.”

- “Recent decades have seen a growing consensus in development theory and practice on delegating to housing markets the supply of affordable housing for the urban poor. This consensus is largely a response to the problems associated with the public housing policy approach where governmental agencies control the production and administration of affordable housing, which was the dominant model in developed and some developing countries in the mid-twentieth century. As this public housing policy fell into disfavor, countries and international organizations have increasingly favored market-oriented housing policies. One particularly influential market-based regulatory discourse in the developing world is the “enabling markets housing policy” approach. Under this model, the role of the government is to provide the general regulatory framework and incentives to encourage the housing supply from the market. More concretely, this regulatory strategy favors the privatization of public housing, the reduction and simplification of urban housing regulations, and the allocation of targeted demand-side subsidies to the poor. The goal is to allow urban markets to operate as freely as possible, and to concentrate the role of governments on stimulating a competitive supply of low-income housing with minimal regulatory constraints.”

- “Is the enabling markets approach effective in promoting sustainable housing solutions for the urban poor? Is it possible to achieve the goals in this social policy sector through this strategy? The objective of this Article is to confront this influential development doctrine with an in-depth case study on the evolution of Chile’s low-income housing policy regime over the last four decades. Chile represents an interesting case to test this policy approach because it was a pioneer in adopting an enabling markets strategy to affordable housing in the 1970s, and it has continued to rely on this strategy as its main regulatory approach to the provision of low-income housing for over forty years. From a quantitative perspective, the regime has been a commendable success. Chile has radically decreased its deficit of low-income housing stock, and has significantly reduced the number of informal urban settlements, which is a remarkable achievement in the Latin American context. As a result, the Chilean model of housing assistance has become very influential in the developing world.”

- “The main argument I present in this Article is that Chile’s commitment towards an enabling markets strategy has helped to reinforce the pattern of urban exclusion, and has prevented the government from experimenting with alternative regulatory approaches that may be more effective in generating affordable housing in a more inclusionary way. In essence, Chile’s enabling markets strategy has relied on the distribution of targeted subsidies to stimulate the supply of low-income housing, in the context of a regulatory framework that favors private real estate development and strongly protects private property rights. However, in practice, the subsidies have rarely been sufficient to allow beneficiaries to compete for well-located housing. At the same time, private companies have had a strong profit incentive to agglomerate low-income housing for subsidy holders in the least desirable urban areas.”

- “This Article proposes an alternative policy strategy, which I call a “planning markets housing policy” approach, employing land-use governance mechanisms to incentivize the supply of affordable housing in well-located neighborhoods. More concretely, this strategy involves linking land-use regulatory processes with the generation of affordable housing in an explicit and direct way. Although some of the instruments adopted under the enabling markets approach are compatible with a planning housing markets approach, the current skepticism about the role of administrative interventions in housing markets needs to be abandoned in order to address the problem of urban exclusion.”

- “The analysis is based on comprehensive fieldwork conducted in Chile between 2013 and 2015, which involved more than fifty interviews with key stakeholders involved in the design and implementation of Chile’s housing laws and policies in the past decades. The strategy behind the selection of interviewees was inspired by the desire to maximize the variety and range of perspectives of the phenomenon under study. The majority of interviewees were, at the time of the interview, acting or former public officials of Chile’s Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (MHU). I also interviewed people working on housing issues in several municipalities in the greater Santiago metropolitan area, the capital of the country: officials from nonprofit and for-profit organizations that act as developers or intervene in the construction and administration of affordable housing projects, persons from the real estate industry, congressmen and representatives of community organizations (who represent the voice of the actual beneficiaries of the policy), and relevant influential individuals from academia and advocacy groups. The information obtained through the interviews was complemented by data from public and private documents, administrative datasets, and other secondary sources.”

- “Many of [the] aims for contemporary housing policies are captured in the term “urban inclusion.” The term urban inclusion may be defined in two ways. One refers to the location of disadvantaged groups in neighborhoods that are adequately connected to public and private services, such as good schools, good health care providers, job opportunities, and so on. The second refers to the actual social mixture within buildings or neighborhoods of families from different social backgrounds. The focus on urban inclusion as a policy objective is at least partly explained by the widespread acknowledgment of the significant impact that neighborhoods have on social and individual behavior, described in the literature as “neighborhood effects.” A large body of academic research and dramatic historical accounts show that neighborhoods constitute important mediators of social life and often have independent impact on human behavior. Moreover, neighborhoods can reinforce existent inequalities between social groups.”

- “In most countries around the world, the housing policy sector has seen a transition from policy approaches where the provision of affordable housing was carried out by governmental agencies operating outside the regular rules of markets, to approaches where the private sector and market dynamics are ultimately responsible for delivering formal housing to low-income families. This transition has occurred in the developed world as well as in countries that have transitioned from socialist regimes to market economies, and even in countries that to a large extent still have centrally planned economies like China.”

- “The main ideas of the emerging markets approach are detailed in a very influential and widely circulated white paper published by the World Bank in 1993. The central idea was to limit the role of governments to the adoption of rules and policies to stimulate the market supply to meet housing demand. The World Bank explicitly sought to move away from an institutional model where governments produce, finance, and maintain housing. The strategy was grounded in the belief that when governments frame their interventions in housing as a welfare issue, they end up transferring public resources to a small group of households and distorting the operation of the housing market. Instead, governments should redirect their attention to embrace the whole housing sector, establishing the regulatory environment and incentives to allow the private sector to be the primary responsible agent for the production and finance of housing, even for the low-income sector.”

- “The core regulatory architecture of Chile’s long-standing market-based housing policy model is the result of the transformation carried out by the military dictatorship that governed the country between 1973 and 1990. While it is true that there have been some variations with respect to the institutional structure shaping the regime, the underlying rationale and many of the main instruments have been maintained throughout this period … Before the new policy model was established, public agencies were responsible for the provision of affordable housing; these agencies operated as genuine real estate developers, similar to the public housing model used by developed countries in the mid-twentieth century. The provision of affordable housing was believed to require an active government role, which could operate through a wide range of possible administrative interventions.”

- “The radical transformation of Chile’s housing policy regime in the 1970s was part of a larger package of neoliberal reforms implemented by the military dictatorship. Two main objectives guided social policy reforms during this period. The first involved the establishment of a “subsidiary state,” by which it was implied that the government should only intervene in those areas that the market could not adequately serve on its own. The objective was to transfer the provision of as many public services as possible to the market and to private entrepreneurship. In this model, the role of government is to stimulate the private sector rather than replace it. The second objective involved reaching the most efficient allocation of government aid to those in most socioeconomic need. The diagnosis of the military government was that social policy was not reaching the poorest families of the country. The primary role of government thus became the design of effective instruments to identify and assist those families that most needed social and economic aid … The philosophy of this model was consistent with the neoliberal prescriptions that the U.S. government was trying to implement in Chile, a philosophy that directly reflected neoliberalism’s particular skepticism regarding direct government provision of public goods.90 In other words, private solutions for public problems.”

- “Since its inception, the core of Chile’s market-based housing regime has been a complex set of subsidy programs targeted to low-income families. The creation of the subsidy programs was complemented by other institutional and legal reforms that together comprise the current market-based regime. Arguably, the most important legal reform was the deregulation of the urban land market. In 1979, the military government formulated a National Policy for Urban Development. The guiding theory of that official policy document was that, in order for the housing market to function properly, land could not be a scarce resource. In other words, land uses should be determined by rates of profitability, and not by urban planning and regulations. This principle was implemented through a series of reforms that dramatically extended urban boundaries in Chilean cities, especially in Santiago, and that reduced property taxes and urban regulations. These policies immediately made much more land available for urban transactions and greatly reduced regulatory constraints for real estate developers. Policymakers from the military regime expected that increasing the supply of available land would reduce urban land prices. Research has demonstrated that this did not actually occur. On the contrary, prices increased, mainly because landowners quickly seized the opportunity for speculation.”

- “There was one aspect of Chile’s former housing regime that the military dictatorship decided to retain: the exclusive focus on subsidizing homeownership. Until 2016, all governmental housing assistance throughout Chile’s history has supported the acquisition of shelter in property rather than rental housing. The common justification behind this institutional choice is the association between homeownership and social mobility—owning a home is supposed to enable low-income families to accumulate wealth through their full participation in a market economy. Security tenure permits homeowners to have access to the financial sector, mortgaging their properties, while promoting overall economic development at the same time.”

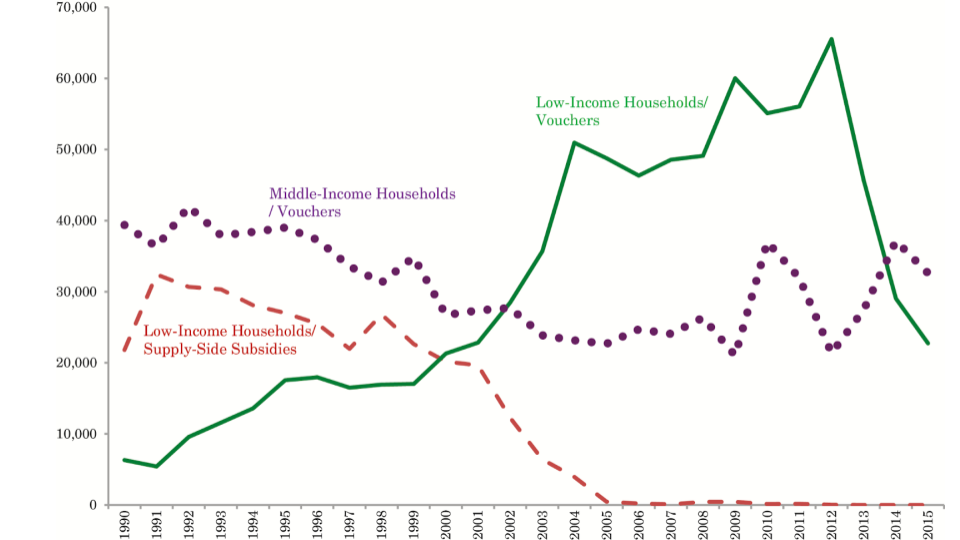

- “Since the 1990s, the subsidy programs have been regulated by numerous executive decrees, and over time some features have varied considerably. However, it is possible to identify three core institutional strategies, which are represented in Figure 1 below. From 1990 to 2015, in total the MHU has financed 1,955,232 housing units to households lacking access to formal housing in the country … Figure 1 shows three interesting facts. First, despite the robust narrative about the need to concentrate governmental aid to assist the country’s poorest families, the truth is that, at least with regards to the housing sector, governmental subsidies have always benefited middle-income as well as low-income families … Second, a voucher-based logic has become increasingly dominant in the regime. The programs for low-income households in the 1990s, represented by the dashed line, operated in practice as a supply-side subsidy regime … Third, housing assistance for low-income households has increased over time. In the 2000s many more subsidies were delivered to the low-income sector than to middle-income families.”

- Figure 1.

- “At the beginning, these programs only allowed the use of the subsidies to purchase a new affordable housing unit. However, in 1996 the regime was modified to allow the purchase of used housing. The subsidy comes in the form of a certificate with a pay order in the name of the subsidy beneficiary, which is paid by the MHU to the builder or seller as soon as the beneficiary proves that the ownership of the dwelling unit has been transferred to her. Usually, the beneficiary has a number of months from the moment the subsidy is granted to prove the transfer of property is complete. All these programs have attributed a passive role to the MHU, which does little more than select beneficiaries and allocate demand subsidies or vouchers to stimulate the housing market for the target population segment. The private sector plays a major role in the implementation of these subsidy programs, which rely on the operation of real estate companies that would attract demand and organize the actual project, including its construction and financing.”

- “One important feature of the programs for low-income households since the early 2000s is that they have not required beneficiaries to take a mortgage loan from the private sector.121 Access to affordable housing was supposed to be financed only with a governmental subsidy and a small percentage of household savings. Indeed, each applicant only needed to prove that they possessed a small amount of savings, which totaled less than 5% of the voucher. In practical terms, the government provides free houses to low-income families.”

- “Another important characteristic of the newer subsidy programs is that the MHU stopped contracting directly with construction companies. Now, the organization of the affordable housing project is delegated to the families who will live there. The details of the implementation of these programs has varied. Most of the time, the subsidy programs have favored collective application to the individual subsidies, where at least ten eligible households had to apply together by presenting an affordable housing project proposal to the MHU with the support of an intermediary institution. The collective application was conceived as a way of encouraging the creation of new neighborhoods and communities through self-selection by families.”

- “Notably, this regulatory framework does not contain rules or regulate processes that may facilitate the inclusion of affordable housing in well-located neighborhoods. The GLUC, which constitutes the basic regulatory framework for urban land use in the country, seldom refers to affordable housing, and basically regulates the process through which national, regional, and local public institutions may define what and how to construct in urban territories. It is focused on ensuring that real estate developments comply with some minimum standards, standards that are detailed in regulations adopted by other public agencies. However, with few exceptions, the legal framework simply does not address the generation of affordable housing and its adequate territorial distribution in urban areas. Moreover, one particular provision of the GLUC, article 55, is very problematic rule from the perspective of inclusionary affordable housing. This article prohibits the construction of urban neighborhoods outside the urban limits of a city, except for the cases of affordable housing projects. This is an explicit invitation to construct low-income housing units in peripheral urban areas that are often badly served by public and private services.”

- “From a quantitative perspective, Chile’s market-based housing policy regime is rightfully considered a big success, because it has promoted massive access to formal housing and significantly reduced the housing deficit in a relatively short period of time. According to official statistics, from 1990 to 2011 Chile reduced the housing deficit from around 1,000,000 units to around 500,000 units; it should be noted that this reduction was achieved despite Chile’s overall population growth and the concomitant increase in housing demand over that period of time, and even despite the effects of the 2010 earthquake that left thousands of families homeless. According to the same source, 86% of the housing deficit corresponds to households that are currently living with another family.142 A significant portion of all irregular settlements has been eradicated, which is quite a remarkable achievement in comparison with other developing countries.”

- “The academic literature began to identify the spatial bias of Chile’s housing policy regime in the late 1990s and early 2000s. A well-known 2005 study of the implementation of Chile’s subsidy programs in the 1980s and 1990s argued that the regime was responsible for the creation of “the problem of people with roofs.” According to the authors, the main problem affecting Chilean cities shifted during this period of time from people living in irregular settlements (informality), to urban segregation of low-income people. Since then, other authors have documented through statistical methods the spatial bias of Chile’s low-income housing policy. These studies have confirmed what most stakeholders had known for many years: the policy structure that Chile has implemented tends to concentrate poverty on the boundaries of Chile’s urban areas. The existence of poor and spatially isolated neighborhoods is today a clear and crude reality in Chilean urban areas. A recent study estimates that 1,684,190 people live in some sort of ghetto in the twenty-five biggest Chilean cities. Moreover, although more evidence is needed, a number of recent studies have shown that the concentration and isolation of low-income families in subsidized housing projects have contributed to negative outcomes for those families.”

- “Why has Chile’s market-based housing policy regime held this spatial bias against the poor? I argue that segregation based on income is a natural outcome of Chile’s commitment to an enabling markets regulatory rationale. This commitment is expressed in a regime that limits the role of the government to the delivery of targeted subsidies aimed at promoting homeownership, within a regulatory framework that facilitates private real estate development and transactions without an explicit concern for generating rules that may promote inclusionary housing.”

- “Given the limitations of the enabling markets regulatory discourse, governments confronting the need to promote access to affordable housing in an inclusionary way should rather experiment with what I call a “planning markets housing policy” approach … A planning approach acknowledges this fact and uses the land-use governance regime to stimulate the supply of inclusionary housing. The basic idea of a planning housing markets approach is that the rules and institutional practices that govern urban development should be designed and implemented in a way that favors the generation of low-income housing in an inclusionary way. In a way, it proposes a strong connection between affordable housing and land-use planning, under the premise that affordable housing cannot compete for well-located land unless there are land-use regulatory obligations and incentives that explicitly promote that outcome. … The idea of using land-use planning mechanisms to incentivize the generation of affordable housing is commonly associated with inclusionary zoning policies. However, a planning housing markets approach should be understood as a broader regulatory rationale, one that addresses the failures of housing markets in generating inclusionary housing in a structural way.”

- “A fully developed policy proposal is beyond the scope of this Article but some core aspects of a planning markets approach for inclusionary housing are outlined here. First, the promotion of inclusive housing should be adopted as an explicit objective of the land-use governance regime … Another important aspect of a planning markets housing policy approach is a legal commitment towards preventing exclusionary urban planning regulations and practices. For example, one strategy for avoiding the construction of low-income housing in well-located land is to adopt zoning rules that do not directly prohibit affordable housing development but that, in practice, make it impossible to build affordable housing … Finally, a planning markets approach should include some form of inclusionary zoning policy, that may enable the generation of affordable housing in market-driven real estate development projects.”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice Podcast, I'm Shane Phillips. This episode Paavo is my co host, and we're joined by Professor Diego Gil to talk about the very big topic of government and markets, and how one specific approach was taken in Chile over much of the past 50 years, with some good outcomes and some bad. This is an examination of what's now known as the enabling markets policy, which effectively left more of the job of housing the urban poor to the private market, and provided demand and supply side subsidies to spur construction. Though as we discussed, the later emphasis was much more on demand side subsidies, which has some real drawbacks. This was in contrast to a previous policy of direct government provision of housing for poor households. Chile is enabling market policy became something of an archetype and the World Bank promoted its expansion all over Latin America, and to give credit where due, it really did create a lot of housing for Chilean residents who lacked formal housing before but as Professor Gil discusses in his article, this approach also helped entrench residential segregation of poor residents into distant neighborhoods with limited access to jobs, school and health facilities, and other amenities. He proposes an alternative that he calls the planning housing markets policy, which strikes more of a balance between government intervention and market provision of housing. One thing I want to note here before we jump in, I refer to countries in this conversation as more developed versus less developed, which is intended as an objective observation about the relative size of their economies and per capita incomes, and as a consequence of that what they can afford to provide to their residents. Every descriptor has its own connotations but I do want to be clear that this is not an attempt to assign value based on a nation's level of economic development nor to ignore the history or global forces that might help explain some of these differences between nations. But I will say that we certainly lacked the expertise to give those topics their due on this podcast. If you have a preferred terminology that you think works better than the one we use here, feel free to share it with me over email or social media. The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, and we received production support from Claudia Bustamante and Olivia Arena. You can send feedback or show ideas to shanephillips@ucla.edu, and you can give us a five star rating or a review at Apple podcasts or Spotify. Now, let's get to our conversation with Diego.

Paavo Monkkonen 2:50

Diego Gil is Assistant Professor at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile and is joining us today to talk about the 2019 article he wrote for the American Journal of Comparative Law. The article is titled 'Law and inclusive urban development: Lessons from Chile's enabling markets housing policy regime'. Diego, welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Diego Gil 3:12

Thank you very much for the invitation. I'm delighted to be here.

Paavo Monkkonen 3:15

Wonderful, and Shane, the regular host is Housing Manager at UCLA's Lewis Center, how's it going to Shane?

Shane Phillips 3:23

I too am delighted to be here. Before we get to the paper, we always have our guests give us a tour of where they live or where they have lived. And we are very excited for this one. You're based in Santiago, Chile. If we're visiting you there, what are the must see spots, especially for folks who have an interest in housing and urban planning?

Diego Gil 3:42

Okay, well, thank you very much again for the invitation. Yes, I live in Santiago, the capital Santiago is a big metropolitan area where around 7 million people live. And from a housing and rural planning point of view, it's an interesting city because as many others right, it shows big disparities, right? There's the downtown area on the eastern corner of the city where you see a good balance of residential, (and) commercial areas - that's the area where most higher income groups live but then you see the rest of the cit in many zones, there's a high poverty concentration, and other problems such as urban urban segregation as we're going to be talking later in this conversation. One interesting aspect, I think, is that to a large extent, and sometimes I think we don't talk much about it in policy discussion, is that that, to a large extent, cities are basically shaped through the way governments implement housing policies right? And what you can see in Santiago, which I think it's very interesting from a housing policy perspective, is that we have neighborhoods that have been constructed through different policy instruments and programs. So for instance, you can see very interesting housing projects that were constructed in the 60s and 70s. For the working class, some of them still exist in the city, and they are very interesting. One, for instance, the one that is very famous is there is the Apportalis which is always shown us one very good example of this modernist architecture style but then will you see other other neighborhoods that have been constructed by other policies, where we are not, of course, very proud about the outcomes that were produced there, right? So like, I think it's interesting in this city that you can see different historical moments where different policies have been implemented, and that have led to very different outcomes in terms of not only the physical shape of the city, but also things related to the welfare of urban residents in Santiago.

Shane Phillips 6:08

Talking about the history, I think, is a good place to start. So let's begin this conversation with the challenges that Chile was facing in the 70s and 80s in particular with respect to housing the urban poor. Before we even talk about the political and economic context of that era which is really important, what was the context more specifically, just with respect to housing, things like access to formal housing, housing quality, things like that?

Diego Gil 6:35

Yeah, well, as in many other policy areas, what happens in the 70s and 80s, is very much linked to the political situation, right. And what happened in Chile is that we had a very unique in some ways military dictatorship that governed the country for 17 years, going from 1973, to 1990. And that military dictatorship was, of course, a very regressive government, a lot of people were killed and tortured. But also, it was very transformative in the sense of these market based neoliberal changes that they made to our economic and social policies, and that they intervene most policies areas in the country, including housing and urban planning. So that was a moment where that government, their military government was basically reshaping our whole sort of housing and urban planning, institutional structure. And I think they were very effective, and I think I mentioned that in the paper, they were very effective in terms of setting up a new system, a new way, of providing housing aid to the lower income groups in the country but they were not very effective from a point of view of providing the sufficient housing solutions to the people that were demanding housing. There was also something that occurred in a context where there was a lot of regression, and they actually they implemented a program where they were eradicating low income groups that were living in informal settlements in in higher income areas of the Chilean cities. That had been very clearly in Santiago, and they were sort of exposing them to the to peripheral areas of of the city. There's actually one very good movie, I think one of the best TV and movies called the Machuca (spelling) that won prizes, and I think it's a good very good example of of how these communities of informal settlement sellers were living in higher income areas in Chilean cities, and they were eradicated by the military dictatorship to other areas of the city.

Shane Phillips 9:12

We kind of jumped ahead there so I want to make sure we cover the military dictatorship implemented this enabling markets policy, it was dislocating displacing urban poor, especially from higher income neighborhoods. But what was the context they were acting with, and what problem were they trying to solve? Because I know, there was a lot of informal housing, for example. What did what did things look like for the urban poor? What form did the city take at that time that the dictatorship was trying to do something about?

Diego Gil 9:42

Yeah, so what there was actually a lot of informal settlements in the in the country. We unfortunately don't have a good data that would trace historically the number of families and the number of informal settlements. We have better data on that, but from more recent years. So yeah, they needed to provide sort of a more formal solution to what was going on with the informal settlements and with many other families that didn't have access to to formal housing. There was also a moment where there was still an ongoing process of migration from rural areas to urban areas, and that was also something that the government needed to respond. And so there was actually a huge demand for formal housing. Actually, there's a famous phrase that you that Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator, that he said, I think that the code is better in Spanish than English, he said that he will transform Chile from a country of "proletarians", of proletarians to proprietarios, to homeowners. He wanted to transform the country in a country of homeowners right? So he really wanted to move people from the informal to the formal sector, and that also has another political dimension. Of course, they was a lot of political activism in these low income communities associated with the opposition to the dictatorship. So the military dictatorship really needed to provide a response to not only because there was a huge demand for formal housing, but also for a political point of view, right for political necessity.

Shane Phillips 11:28

Yeah, I think there's a parallel here in the US back in the 30s 40s 50s with, you know, the government and elected officials trying to kind of push homeownership here for similar reasons, among others but one reason being this idea that someone who owned their home owned land owned property would would somehow be less radical and more conservative, just generally, which I think, you know, is true in some regards, for better or worse. As your article walks us through, Chile took a market oriented approach to addressing these problems, or what the World Bank would later call the enabling markets policy. This was very much in line with the philosophy of the Pinochet regime at the time, though Chile was by no means unique and taking that approach. What is the enabling markets policy? And how did it differ from policies of the past that involve more direct government intervention?

Diego Gil 12:26

Yes. So when when I talk about the enabling markets policy, I basically, I'm basically using the terminology of the World Bank, there's a very famous 1994 report from the World Bank, delineating the main aspects of these enabling markets, policy regimes and actually one of the countries that they use as an example is Chile. Now, of course, there's a lot of diversity within this framework, and you can define different emphases. In the case of Chile involve a significant transformation in the way government provided affordable housing to the lower income groups, right? So before this transformation that occurred in the 70s and 80s, basically, Chile had a sort of public housing model, if we will use if we could use the terminology that is used in the US and other countries, right. Basically, there were some government government corporations that acted as real estate developers basically, and they controlled the organization of the demand for affordable housing, the design of the policies that were constructed, and the allocation of the units that were constructed under heavily government control agencies basically. One important difference between this public housing model and the one that was implemented in the US, for instance, is that basically all housing units were delivered to people that were converted into homeowners - these were sort of homeownership subsidies that were granted by the government. You would acquire a housing unit with full property rights, it was not a rental housing. So in some way, this was a model that was heavily controlled by the government in the sense that public corporations designed and constructed the housing units but after they were delivered to low income households that qualified for those units, basically the government stopped the engagement with these housing solutions. And then when peculiarity of the Chilean military dictatorship of the 70s and 80s was that he basically implemented a big transformation in most social and economic sectors. This happened and it's actually different from what how other military dictatorships in Latin America. This happened in Chile because basically a group of economists, which are called the Chicago Boys, because they were Chilean economists that were actually professors at my same university, and that were trained the University of Chicago's Department of Economics. They basically convince the military junta to implement this big neoliberal transformation in their country. And that, of course, affected most social policy sectors including housing. In the housing area, basically, the government decided to transform completely the way government was involved in the production of affordable housing, with the idea that private solutions were better than public solutions, right. So basically, it delegated to the private sector, most of the responsibilities of the provision of affordable housing for the lower income groups, and the philosophy behind it was to try to limit the government's role to provide targeted subsidies in order to generate competitive system of suppliers of affordable housing right. So basically, the government's limited its role to allocate targeted subsidies to eligible households, and they also limited, and changed completely the land use regulatory system to create a framework that would be more favorable for the private construction of housing projects. So those are, I guess, some of the main characteristics of these enabling markets regime. There's been a lot of change, of course, after this system was set up. But basically, through this, I would say, I think it's plausible to argue that the general architecture of these regime has been maintained.

Paavo Monkkonen 17:13

Yeah, and I think internationally as well, it's still kind of the dominant framework for thinking about housing policy and full disclosure, UCLA, I think Emeritus Professor Powell Harberger, was at the University of Chicago teaching some of the Chicago Boys I think, so UCLA is implicated in this as well. I was thinking maybe just to give a recap, for people that are familiar with this kind of ideological history of international housing policy, like to the extent that there are trends globally, I think, you know, we think about the 50s and 60s, this modernist effort to build public housing and multiple large multifamily blocks in a lot of countries, at the same time, combined with a lot of urban renewal practices of destroying older neighborhoods, especially poor, you know, minority neighborhoods. And then in the 70s, something that kind of didn't come up I wanted to highlight was like the 70s, the work of John Turner, and the kind of recognition that informal, self built urbanization processes were like a valid path to....

Shane Phillips 18:15

self built as in like, the actual residents themselves, kind of

Paavo Monkkonen 18:19

exactly

Shane Phillips 18:20

spurring, the, you know, contracting for the development of their own housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 18:24

Yeah or even, you know, physically building it themselves right. I mean, I think that's kind of the context in a lot of Latin America in the 70s, was massive movement to the cities, from people from the countryside, and no kind of formal housing providers building, you know, subdivisions for these people, and they would just build housing for themselves. And so Turner's emphasis, and others, like Charles Abrams, was that government should support this process, right, and one of the things that, you know, the neoliberal people latched on to was support this process by legalizing it but you know, a lot of those other advocates like Charles Abrams, were saying, support this process by subsidizing materials or helping people you know, with architecture or kind of giving people more direct assistance. And then kind of the other important academic work in the 80s was by Hernando Desoto, from Peru and he's a really one I think that his work, I think it was like 85 or something, El Otro Sendero, (meaning) the other path and talking about how government regulations in Lima prevented people from following the rules because there were just too many rules, and it would take so long to get anything approved, and that really informed a lot of this kind of enabling markets approach to say like, well, we should allow housing to be built in a way that it's inexpensive and accessible to people. And it's like, I mean, it's such a fun thing to talk about with students. I teach this topic in my class, it's one of the themes because, you know, on the one hand, this enabling markets document did a lot to stop important subsidization and social housing programs to help people stop doing that and maybe they wanted to stop doing that anyways. But on the other hand, it brought government action into the housing policy discussion in a way that it really hadn't been before. So it emphasizes infrastructure provision for new subdivisions, and it emphasizes kind of planning as a housing policy in a way that previously people I think hadn't thought about. So I think that aspect of what you mentioned how Santiago expanded its urbanizeable land in a way to accommodate population growth. I think that didn't happen in a lot of other kinds of cities in Latin America, and as a result, people were forced to do illegal, you know, self build housing, rather than being accommodated by the state to build, you know, some kind of low-quality housing but you know, in a formal sense.

Shane Phillips 20:44

Yeah, and I would like to come back to some of the motivations behind this shift and the tensions in that approach in a few minutes. But I do want to, before we move on, just talk a little bit about the results of this approach in Chile. I know, it's neither all good or all bad in terms of what happened as is usually the case with these things. There were big successes, and also plenty of failures and shortcomings at the same time. Could you just sketch that history out for us a bit, and as you do, I think it'd be helpful to introduce our listeners to two important terms that you define early in the article - 'adequate housing' is the first, and 'urban inclusion' is the second. So to restate that, what were the results of Chile's enabling markets policy, and how do the concepts of adequate housing and urban inclusion influence how we look back on those results?

Diego Gil 21:42

So I use these two terms, which of course as every policy goals, such as adequate housing or running tuition, they respond to the frames that exist in the periods of history where these terms are used, right? So how are we defined today adequate housing, for instance, is probably different from how it was defined several decades ago, right? Usually, adequate housing refers to providing housing that meets some minimal quality standards, basically. And I think that sense Chile's housing policy has made a lot of progress, right? Remember that Chile's a country that is shaken every once in a while by big earthquake so usually, there's a strong focus on having good quality building standards, because of course, like houses, and our infrastructure is affected by these earthquakes from time to time, right. So, in that sense, I think that there's been a lot of progress in the in the past decades. The other term is urban inclusion, I think urban inclusion could be defined in two ways or it's usually defined in two ways when we, when we see the literature or when we talk to policy experts, right? One way that is often used in policy circles is the fact that in housing should be connected to the urban infrastructure and to good quality public and private services that are often offered by cities, right. So it basically refers to the connection of affordable housing to the opportunities that cities usually offer, right? Labor centers, education, on health facilities, etc. A second definition of urban inclusion is more related to social mixture, the fact that through housing, you would promote the connection and the relationships between groups that belong to different social classes, right. So of course, the way you frame the term, urban inclusion will shape the type of programs and policies that you implement, right. It's different to promote housing that is well served by public services than promoting housing that allow low income groups to be close to other social groups. So going back to the history of Chile's housing policy, and I think this also connects to the comment that Powell was making so the dictatorship in the 80s was very effective in terms of setting up a new institutional, new policy architecture, but it was not very effective actually in reducing the housing deficit. So what we see on the advocacy, as you see appear in the data and show part of that data in my paper, is that in the 90s, and the 2000s when democracy resumed in Chile, we had, like the first democratic government after the dictatorship started in 1990. Those government were much more effective in terms of providing housing to the lower income groups. So the housing deficit in the country was reduced significantly throughout the 90s and 2000. In terms of the quality of housing, at the beginning, there were many troubles and problems in terms of the building standards that the private sector was using when building housing products for the poor with public subsidies. But with respect to the quality of housing, I think, throughout the years, those standards were improved. I think the big failure has been urban inclusion because especially in the United States, and also to some extent 2000, and you can also see some of those problems still in the way policies are implemented today, you'll see that this is still a policy that incentivizes the agglomeration of low-income households in cheap land, usually locating the least desirable areas of the city right. So what basically I argue in the paper is that from a quantitative perspective, the housing policy implemented in the past decades have been quite a success but from the perspective of urban inclusion, I think it's fair to say that there's been many shortcomings of this institutional model.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:44

Yeah, it's interesting kind of trade-offs there between, I think I've heard other people talk about in terms of right to housing versus right to the city, so you can provide a lot of housing, but it's inaccessible to the benefits of the city itself.

Shane Phillips 26:59

I did want to clarify, you use the phrase housing deficit, which I think might not be familiar to many of our listeners. This basically mean a shortage of formal housing units relative to the number of people, so it's sort of like the number of people that are currently living in slums or shanties or kind of makeshift shelter who need formal higher quality housing.

Diego Gil 27:22

Yes, there's actually a technicality there. Yeah. So housing deficit is basically the measure that the government uses to estimate the number of housing units that need to be constructed in order to replace housing that were that doesn't meet minimum building standards criteria, and also, housing units that need to be produced in order to house people that are living with others or that do not have access to formal housing, but it doesn't include informal settlements. So when we talk about the housing that is in Chile, we usually need to combine the number of people that are part of this official statistics with the number of people that are living in informal settlements.

Paavo Monkkonen 28:15

For the Housing Voice completors, you can refer to an episode recorded with Nick Marantz and Echo Zheng where we talked about California's methodology for estimating housing, we don't call it deficit here, but thehousing needs, right. Then this quantitative population growth element and the qualitative like overcrowding and poor quality housing, but the informality thing is interesting maybe we'll get into it later.

Shane Phillips 28:38

One question I had, which I realized the paper didn't really touch on is where is the housing for low income households being built? What does it look like? I gather that it's suburban and character but is that the whole story, is it kind of like what we talked about with Dinorah Gonzalez about Mexico suburbanization where it's just kind of whatever land happens to be available at the urban fringe, and not only the schools and parks and so forth, that are available, but even the roads and infrastructure are not really developed?

Diego Gil 29:09

Well, there's this, of course, always some heterogeneous result results right - not every project is the same, right? But when we talk about urban segregation in Chile, we mostly refer to housing projects that are very dense, and are usually constructed in the fringes of our cities. That's actually very dramatic in Santiago, because there is a very big metropolitan area, right? So some of these projects are very far from the downtown area, let's say in the case of Santiago, and I think the data shows this in a very eloquent way. Most of these projects built in the 80s, 90s and 2000s were actually constructed in the southern and western limits of Santiago, and this has produced a very interesting pattern because in a city like Santiago, we have very high density in the downtown areas as happens in most cities, right but also in the areas that are close to the urban limit. There's been some changes from here, and then, a municipality that works well with a community is able to construct an affordable housing project in a better-located area but the average outcome of this institutional model has been the agglomeration of low-income households in the city limits, usually in those limits that are not well served, that do not have good access to transportation system, do not have good coverage of parts and green areas, etc, as you may imagine, right?

Paavo Monkkonen 31:02

That's interesting. That's kind of like a lot of European cities have a similar density pattern, because it's harder to redevelop, you know, it's harder to build new midrise buildings in the edge of the city, you know, unless you're doing greenfield development,

Diego Gil 31:15

We, with a colleague, from the School of Government, Paulo Ceraille who is an economist, we wrote a paper that we published in Cities, where we compare a sample of low-income households that live in formal housing with a sample of low-income households that live in these formal subsidized housing projects. And it's interesting, this is a survey that was conducted in 2008, and it's interesting that, from the perspective of many welfare outcomes, people living informal settlements report better outcomes than people living in these formal subsidized housing projects. In terms of location, for instance, usually informal settlements today are better educated than men from housing projects. People in informal settlements commute less to their work, they are more satisfied with the neighborhood where they live, etc, etc. So I think it's interesting that despite all the effort, and all the money that the government has put in order to promote the construction of these low income housing projects, in terms of like the welfare of the residents, I don't want to generalize to every situation, of course, but sometimes people living in informal settlements are better off than people living in these formal housing projects.

Shane Phillips 32:38

Yeah, let's dig in on the policy itself, and what the reforms actually looked like to make this enabling markets policy happened - what is it in terms of how it treats land use restrictions and regulations, how it treats developers, what public funds are being spent, and on whom and where all those things. What is the enabling markets policy in a more technocratic sense?

Diego Gil 33:05

Yeah, I can provide a very concrete actually, picture of how this policy operates right. So well, we have a Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning in Chile, right, which is sort of the equivalent of HUD, this this minister was created in 1965, but was totally reshaped during their military leadership. From the transformation of the 70s, when I was doing the fieldwork for my doctoral dissertation, people would refer to the Minister of Housing as a machine of subsidy delivery. And basically, the Minister of Housing has two main departments, the Department of Housing Policy and the Department of Urban Development. The most important one, the one that spends probably 70-80% of the budget of the Ministry of Housing is the Department of Housing Policy, and basically, that Department operates the housing subsidy programs. So basically, the Minister of Housing what it does, is to administer a set of housing subsidy programs that are designed to stimulate a competitive supply of formal housing. And it has sort of two types of subsidy programs, one for middle-income groups where middle income families can apply, and they get a voucher from the government that they need to compliment with credit from with a mortgage from the private sector and with savings, and with that, they can go to the private market to acquire housing remember that is our only homeownership subsidy - subsidies are designed for people to use to buy a new or a used housing unit. And the second line of programs are the subsidy programs for low income groups, which are the bulk of the effort the budget spent by the Minister of Housing, which are today are basically subsidy programs where the government subsidizes 95% of the cost of housing, it has to be complemented by a minimal amount of savings, and where individual low income families, or a group of low income families can apply and get the subsidies in order to buy a new or a US housing unit. Most of the housing subsidies that are delivered to low-income groups in Chile go through this collective application process where a group of low-income families applied together to the subsidies with a sponsor or a private company or a nonprofit company, and they apply they get the subsidies, and with that money, they build a formal housing condominium that they finance with the money provided by the government. That's basically the bulk of what the Ministry of Housing does. It also has this Urban Development unit, but they have much less budget, and they are basically focused on trying to set up some regulations for the urban development in general to provide some interpretations on how those regulations applied to the private sector and said about the in terms of like the how housing policy operates, it basically operates through these government subsidy programs. I have to say, though, that a few years ago, the government started our rental housing program, which was really an innovation. And it was mostly based actually on the section eight voucher program of the US but that...

Paavo Monkkonen 37:07

in a very sexist manner, "Cioa Suegra" yeah, yeah, "goodbye, mother in law!" like for young couples, or something that's such a strange national policy.

Diego Gil 37:21

I can mention the story is that basically, most of the people that lack affordable housing delay lives with others, right live within families. This is very common in lower-income groups, and it's even common in the Latin American culture for affluent groups. But they also counted as part of the housing deficit. So the government decided to implement these new programs in order to allow young families to separate from their families and to get a new housing unit but they use these very problematic terminologies "Ciao Suegra: Ciao Mother in law" that produce a lot of like conflicts and basic criticism in the policy service.

Paavo Monkkonen 38:05

Yeah, but more seriously, I mean, it's fascinating that the shift was towards demand-side subsidies as like the neoliberal model proposes, but in the case of Chile, and a lot of Latin America, downpayment assistance for homeownership rather than rental assistance from the beginning. And I think like you mentioned, the ideological motivations for that, even though in the US, you know, we have a similar homeownership ethos. So I wonder if it was also just the kind of practicality or cost - the technical aspects, you know, it's easier to administer a one time payment to somebody than it is to kind of run a program where you're subsidizing rents in a complicated manner for a lifetime. I don't know if you have any insight into the creation of that and the discussions at the time?

Diego Gil 38:48

Yeah, that's a very good question. And actually, it's part of what I like to, to work a little bit more in the future, right, for my research agenda. I think that yeah, there's some of the causes behind this emphasis on of homeownership might be with the lack of state capacity, which is a very common feature in Latin America. Volunteers have been more say capacity than other Latin American countries. You see why, for instance, our rates of informal settlements is much lower than in other Latin American countries, right and cities. But still, I think, of course, rental housing involves a much more sophisticated structure in order to administer this subsidy that you will give a unique to be renovated from time to time. Now, again, going back to this idea of neoliberal marketplace ideas, what's interesting from this rental housing program that was adopted a couple of years ago, is that they basically focused on the demand side, right. So they created a program and they started to implement this demand side voucher for rental housing, and one of the main outcomes from what we see in the research is that most people cannot find housing rental housing with the price of the subsidy. So the take up rate of the rental vouchers is very low, it's about 14%. In some cities, I think it's up there was even lower right, and, again, the problem is that the government needed didn't complement these demand-side interventions with other policies that would stimulate more directly the supply of rental housing, that's the main cause. Now, this also some resistance to the idea of rental housing, there's also a culture of homeownership that I will say it's very rooted in the Chilean and Latin America, in other countries as well so it's not easy to have the government focus only on rental housing in a country like Chile.

Shane Phillips 40:57

I did want to know that the collective application process that you mentioned earlier, for the low income groups, trying to you know, buy or build housing reminds me a lot of our conversation with Hayden Shelby about the slum upgrading process in Bangkok actually, and how just a lot of responsibility was sort of offloaded onto these low-income households who were basically, you know, on the one hand, it's great that they have more autonomy. On the other hand, this is a complicated process to figure out, like how to build a neighborhood together, even if you've got some subsidies. And so I don't think we have to get into that, we could refer people to our discussion there but I think it's interesting. I think it's fair to say that this was not only a story of a sort of pro-market bias in housing policy, but something of an anti-government bias as well. But in the article, you bring up what I thought was an important distinction in the source or the rationale of these biases in less developed versus more developed countries. In most cases, developing countries have fewer trusted institutions, they have more concerns about corruption and less state capacity. And in that sense, it's understandable why some people might not want to rely on government to solve these big problems. Could you expand on that idea a little bit? Does it seem like a valid concern to you or do you think there are good enough examples of other developing nations figuring this out in maybe a more balanced way?

Diego Gil 42:30

I think that's a very interesting point. It looks it seems to be very valid.

Shane Phillips 42:36

I guess I should add that like, you know, if you've got this corruption on sort of the institutional political side, there's no reason to think you wouldn't also have it on the private side. So maybe, if not, that's not a good argument on that in that regard but I imagine it was an argument that was put forth.

Diego Gil 42:54

Yes, on a more general level, I would say that, I think it's intuitive to when you have a country with lower state capacity. I'm speaking in general, not in a country-specific, right. But when you have a country with low state capacity, I think it's intuitive to rely on policy instruments, that would, in a way, try to produce some outcomes, considering that those outcomes cannot rely on a strong bureaucracy and efficient bureaucracy or solid public agency right. But my impression is that less low state capacities, it's always a problem for complex policy problems, you need to build a good state capacity. And I think what we were talking about when we were talking about the demand side subsidies, I'm not against the demand side subsidies, they could be like a good efficient instrument to allocate subsidies, to try to promote certain outcomes, etc. But when we see in housing markets is that if you don't complement demand-side strategies with supply side strategies, you're not going to produce good outcomes. In the case of homeownership subsidies, for instance, one of the problems that the evidence of the TNM case shows is that basically, the price of the subsidy, is always negotiated with private developers, right? You need to have a price of a subsidy that you would guarantee that would stimulate some level developers to construct affordable housing. But what happens from a moral structural point of view is that when you're selling up that price, you're basically setting up the price for the land that is the least desirable of the city, especially when you have a fixed subsidy price. If you have a mechanism to provide different prices for a city, you may have a different market response. It has always been a very homogeneous price of the subsidy programs, right. So what happens is that basically, the price of the subsidy provides a signal for the amount of money that the government is able to provide in order to construct housing in some places. And then the rest goes, basically is set up that the price of the subsidy, right? So that's why we have seen and I think there's good research about it, we have seen that it's very difficult, with only a demand side intervention, to promote affordable housing, in relegated places. You almost never are able to compete for relevant land, with this type of demand side subsidy strikes. That's why I think that, at the end, given that it's a very complex problem, and it's very difficult to counteract the housing market dynamics, you will need to have a more sophisticated, say capacity and more sophisticated regulatory interventions in order to promote more directly the supply of affordable housing in well-located places.

Paavo Monkkonen 46:20

It really reminds me of another country with low state capacity, the United States of America, and how our low-income housing tax credit program also builds affordable housing and neighborhoods that on many indicators are not considered kind of high resource or high opportunity neighborhoods. A recent graduate from our PhD. program, Xavier Qui, will put his a link to his dissertation in the show notes, but he shows that yeah, in fact, people moving into new low- Income Housing Tax Credit buildings are getting much better quality housing, but they're moving to "worse" kind of by standard metric neighborhoods so we also have the the same problem in our system.

Shane Phillips 46:59

I also think it's important to note that the housing problems we're talking about differ in less developed versus more developed countries. In less developed countries, the problem tends to be too little formal housing period - very large shares of the population may just lack formal housing altogether. These places are tasked with creating a lot of housing, really from scratch, which of course, is a huge undertaking, and all the more so for not having a lot of resources or state capacity to carry that out. In more developed countries like the US, the vast majority of people are housed in the formal housing sector, and so while we certainly have our own problems, they can feel more manageable, I think, like something we can get our arms around. Does that ring true to you? I just feel like this is an important distinction because we're talking about Chile but you know, many of our listeners are coming from the US. I want to make sure we have a sense for the different challenges that they're trying to tackle.

Diego Gil 47:58

Yes, well, Chile is classified as a middle income country. I think the outcomes that we see in the housing field broadly reflect the fact that we are a middle income country. The number of families that live in informal settlements in Chile is much lower than what happens in many developing countries, such as Brazil, for instance, and other countries in other continents as well. But yes, we do have a problem of informality, which has been actually growing there in a couple of in the past couple of years. There's many hypotheses behind this - there's a lot of strong integration process to Chile in the past years, and lot of people, we have seen the emergence of a lot of informal settlements in the northern area of the region. Also the pandemic, I think hit very, very hard, low-income groups and maybe forced many of them to live in these informal communities. So it's true that that's actually a big problem. Not sure whether it's more complicated or easier to navigate that sort of policy dilemma, versus others that are shown in countries like in the US. I lived in the US for many years, I studied their housing problems - I think they are mainly complicated

Shane Phillips 49:27

Doesn't feel any easier to solve.

Paavo Monkkonen 49:31

Yeah, I don't know. I feel like it doesn't to me, but I was

I was thinking that it doesn't ring 100% true to me. I mean, I think part of it is like the question of the minimum quality of housing that's acceptable to people. And the idea of defining like an informal settlement as like an unacceptable place to live. I think that you know, I would much rather have Los Angeles, tolerate, you know, very low quality housing such that people don't have to sleep under the freeway right? And you know, so I think that's an issue in Latin America as well where, you know, this push to say, "no, that shantytown is not acceptable!", and you know, what do we do about that rather than supporting kind of people's housing where it is and improving it. Yeah, I mean, I think the resource differences are often very large, but then it's just political will and like, you know, we have a lot of money in the US, we just don't spend it on lower-income people.

Shane Phillips 50:24

And I do think that, you know, where do you draw the line, and what is acceptable housing might differ based on your country's your level of economic, I think you've seen the same things in the US as in other places where there's this impulse to say, that is unacceptable housing, and we're going to ban it or make it, you know, untenable in some way. But then we're not necessarily going to provide the resources to make the kind of minimum alternative viable for your, or affordable for you.

Diego Gil 50:55

Let me say something about the housing elements in Chile, which I think illustrates some of the points that we were talking. So I think Chile is a country that could address the problem of informal settlements, for sure, I think it has the resources, or it could make the arrangements to have the resources to tackle these problems - probably is the same with the US with all the people that live in homelessness, all the people that are addicted or do not have easy access to housing, right. Or at least they cannot live in the place where they would like to live. So I think these are countries that certainly they could have the possibility of addressing that problem. But I think that what's happening, my impression in Chile with the emergence and with the increase of the number of families living in informal settlements in the past year is that informality is reflecting a deeper and structural problem. And to a large extent I think, an informal settlement is not only a problem of lack of access to affordable housing. The broadening my view is a little bit, it's bigger than that. It represents the fact that the government cannot really address the real needs of families that need access to formal housing. So what's happens and I think the research that I referred earlier speaks to it, is that sometimes living in informal settlements with all the problems that are associated with living for myself, because it's really dramatic situation - you don't have access to a sewage system, you don't have access to clean water, and, of course, has a lot of problems in informal settlements but even with all those problems, sometimes people prefer or are forced to live in these communities rather than using the subsidies or getting access to the former options that the government is providing right? So I think there are some deep structural issues where the informal systems are mostly the symptom, right? The same with exclusion, right, we've been having a huge trend of migration, and abortion, not the majority, but important portion of people living in urban centers, are migrants. Migrants there that want to have opportunities in this country, opportunities that they lacked in their home countries, but there's no easy way to transition to the country to get the paperwork, to have a visa, to get some level of some sort of formal housing. So I think that this informal settlements is reflecting a more complex problem is not what happened probably in the 60s or in the 50s, where basically, the state didn't have the resources to set up a continuous policy instrument to provide housing for the poor. Now, I think this is representing a more structural problem, the fact that the government needs to provide more sophisticated housing solutions, and they're not doing it. We're not doing that. And I think that's part of what we're seeing with this decision.

Shane Phillips 54:23

Now, one thing that actually came to mind as you were talking about this was thinking about the unhoused population here in Los Angeles and in many other places how sometimes they can be criticized for not going into shelters that are provided without there really being any acknowledgment of all the restrictions that are placed on people who sleep in shelters, and just the environment that they're being subjected to kind of reminds me that there's an analogy there - people who prefer to just live in informal settlements rather than sort of take this inadequate deal in some cases that the government is offering. I want to make sure before we go that we do talk about alternatives, you know, the paper is kind of critiquing this enabling market's policy but you've proposed an alternative, which you call the planning markets housing policy, what does that look like?

Diego Gil 55:18

What I tried to do in the paper is not to provide like a fully detailed policy proposal to solve all these housing problems that we have been talking about. It's mostly to provide a framework for different policy rationales that could be adopted and implemented in order to provide a more strong response in the housing field. In the paper, I differentiate three sorts of policy rationales - one is when the government acts as a developer, right, and we saw that strongly in many developed countries, but also in countries like Chile, where government agencies were basically in charge of constructing and organizing the production of low-income house. A second rationale is when the government basically limits its role to finance, to implementing finance mechanisms to promote the supply of affordable housing, and I see that I think that Chile transition, I think the US is our comparable example - transition from a model where the government control, and the production of affordable housing to model where the government limits each role to the finances of affordable housing. A third rationale is related to what I labeled in the paper planning housing markets approach where basically, the government uses land use regulations, obligations and incentives to promote the generation of low-income housing in well-located areas of cities. I know I've read the experience of inclusionary zoning and other mechanisms, you had a really interesting talk in the previous episode of the podcast, I think about the interest rate zone, and yeah, of course, there's no magic bullet here. But I think that in capitalist societies, and societies like Chile, governments need to build up a better regulatory system in order to be more strategic in terms of planning the growth of our cities, and in that plan, inserting mechanisms to incentivize and promote the generated generation of affordable housing in a more fair way, throughout the urban areas.

Shane Phillips 57:46

And last question here for me, sort of big picture and building on what you're talking about with planning housing markets policy. For myself, I believe, pretty strongly that there's a role an important role for the market, and there's an important role for government and government, in many ways, shapes, markets, and this, you know, this dichotomy of it's either you have a market approach, or you have a government approach just rings untrue to me. So like, how do we move forward? How do we get the most we can out of the market, while making sure that the government is doing, you know, as much as it can, but maybe no more? This is a very simple question.

Paavo Monkkonen 58:27

A very simple question Shane, you have three minutes to answer that.

Diego Gil 58:34

Difficult to answer, righ?

Shane Phillips 58:36

It's difficult, but I feel like it is the question. For me, it's the question at the heart of your paper, and in many ways at the heart of the entire housing policy debate we're having across the US and across the world.

Diego Gil 58:50

Yeah, I I believe that governments need to borrow money, right? Actually, we need to unload it, and I think the US and Europe provides good evidence about this, that sometimes when governments control their policy solutions, they produce really bad outcomes, right? Housing segregation in the US for instance was the result of bad policies that relied strongly on public agencies, and that was actually one of the reasons why the US moved to more market-based mechanisms. It was not only an ideological trend, which was part of it, but it was also an acknowledgment of the failure of the bulk housing model. The same with dealing with when housing corporations operate mostly as developers, basically, the government was able to produce really nice housing projects, some that today are very iconic, but they didn't have the ability to magnify housing solutions and the number of families that need housing was very, very high. So through these enabling markets policy strategy, the government was able to magnify access to affordable housing. So I think we need to be pragmatic, and I think there's no magic solutions. The same for instance, we could make the bar with land use regulations we see in California is one of the many examples of land use regulations that are too strict, you cannot build anywhere, right? But when we deregulate the land use market, we also see very bad outcomes. I think governments need to be strategic, need to be pragmatic, and they need to search for a good balance, and I think that building a robust regulatory framework that could really generate a more important balance between public and private interests, that would allow government agencies, municipalities to negotiate with other developers in order to incentivize the production of affordable housing well located. There's no magic bullet again but I think that we need alot pragmatism, and especially we need to diversify our instruments that we have used. Ee need to experiment with new alternatives, and we also need to diversify - one of the things I think that the GM case show with is that it has focused too much on one single instrument, these targeted demand-side subsidies, and they have not been enough. They're like, philosophically right but they need to be complemented with other strategies, and that's why that's sort of the main claim I made in the paper.

Paavo Monkkonen 1:01:50