Episode 31: Inclusionary Zoning with Emily Hamilton

Episode Summary: Cities have lived with exclusionary zoning for decades, if not generations. Is inclusionary zoning the answer? Inclusionary zoning, or IZ, requires developers to set aside a share of units in new buildings for low- or moderate-income households, seeking to increase the supply of affordable homes and integrate neighborhoods racially and socioeconomically. But how well does it accomplish these goals? This week we’re joined by the Mercatus Center’s Dr. Emily Hamilton to discuss her research on how IZ programs have impacted homebuilding and housing prices in the Washington, D.C. region, and the ironic reality that the success of inclusionary zoning relies on the continued existence of exclusionary zoning. Also, Shane and Mike rant about nexus studies.

- Hamilton, E. (2021). Inclusionary zoning and housing market outcomes. Cityscape, 23(1), 161-194.

- Manville, M., & Osman, T. (2017). Motivations for growth revolts: Discretion and pretext as sources of development conflict. City & Community, 16(1), 66-85.

- Bento, A., Lowe, S., Knaap, G. J., & Chakraborty, A. (2009). Housing market effects of inclusionary zoning. Cityscape, 7-26.

- Li, F., & Guo, Z. (2022). How Does an Expansion of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing Affect Housing Supply? Evidence From London (UK). Journal of the American Planning Association, 88(1), 83-96.

- Schleicher, D. (2012). City unplanning. Yale Law Journal, 7(122), 1670-1737.

- Phillips, S. (2022). Building Up the” Zoning Buffer”: Using Broad Upzones to Increase Housing Capacity Without Increasing Land Values. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

- Background on the inclusionary zoning program in Los Angeles (struck down in court, but later enabled by the state legislature).

- More on housing voucher policy in our interview with Rob Collinson.

- More on minimum lot size reform in our interview with M. Nolan Gray.

- A blog post questioning whether new market-rate housing actually “creates” demand for low-income housing.

- Los Angeles Affordable Housing Linkage Fee nexus study.

- “Inclusionary zoning (IZ) is a policy under which local governments require or incentivize real estate developers to provide some below-market-rate housing units in new housing developments. IZ proponents promote it as a tool to address the important public policy concern of access to affordable housing for households of diverse income levels. Its name indicates that its creators view IZ as an antidote to exclusionary zoning policies. Exclusionary zoning rules include minimum lot-size requirements, multifamily housing bans, and other rules that limit the housing supply in a jurisdiction, thereby driving up housing prices (Ikeda and Washington, 2015) … Although IZ may be intended to address the serious consequences of other land use regulations that limit housing supply and drive up prices, economic theory predicts that IZ could actually exacerbate regulatory constraints on housing supply. As legal scholar Robert Ellickson explains, IZ is a tax on the construction of new housing units and a price ceiling on the units that must be set aside at below-market rates (Ellickson, 1981). Both of these factors can be expected to reduce the quantity of housing supplied, resulting in higher prices for units that are available at market rates.”

- “Some past empirical work on the effect of IZ on housing markets has not distinguished between the effects of mandatory and optional IZ programs, but theory says they should have different effects. Mandatory IZ may be a tax on new housing if the cost of providing below-market-rate units exceeds the benefit of density bonuses or other offsets to developers. Optional IZ, however, allows developers to participate in the program if the value of the density bonuses exceeds the cost of providing subsidized units. The introduction of optional IZ should either lead to increased housing supply and lower prices relative to a jurisdiction’s status quo or have no effect if developers elect not to participate in the program … In this article, the author reviews the empirical and theoretical evidence of the effects of IZ on housing market outcomes and contributes a new analysis of the effects of IZ on house prices and new housing supply in the Baltimore-Washington region.”

- “Although IZ programs continue to proliferate, their effect on housing market outcomes remains in debate. IZ advocates often promote two key goals for these programs: (1) promoting mixed-incomehousing development as a tool to reduce socioeconomic segregation and (2) serving a populationthat may struggle to afford market-rate rents in their neighborhood or jurisdiction of choice (particularly new-construction housing) but who are not recipients of other public assistance forhousing that is typically targeted toward a lower income population.”

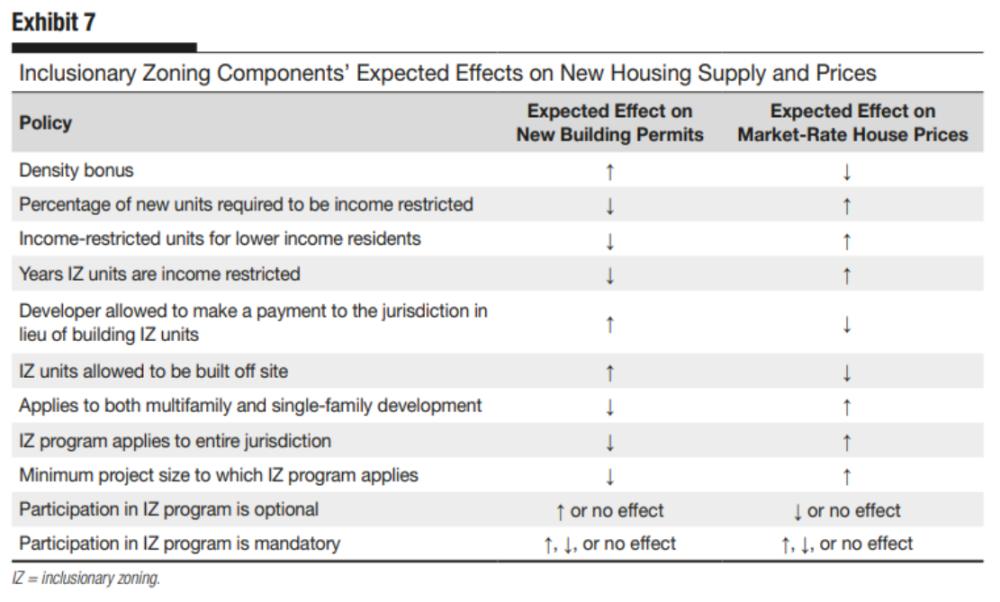

- “Given that IZ programs vary widely in their implementation, economic reasoning will predict different effects on housing market outcomes from different specific programs. Exhibit 7 describes how common aspects of IZ programs can be expected to affect new housing supply and, in turn, prices, all else equal. An explanation of how each aspect of IZ programs can be expected to affect housing markets follows.

- “Components of typical IZ programs contribute to the “IZ tax,” whereas others are an “IZ subsidy … To explore the relationship between the characteristics of IZ programs and housing market outcomes, the author creates two indices of characteristics of these programs. The first, the IZ tax index, measures the five key factors that add to project costs under IZ programs. These five components are the minimum project size IZ requirements apply to, equal to 1 if IZ applies to projects of 20 units or fewer (the median project size that triggers IZ); the second component is the percent of set-aside units required, equal to 1 if the program requires at least 11 percent of units to be below market rate (the median requirement); the third component is the minimum affordability period, equal to 1 if units are required to be set aside for 30 years or more (the median requirement); the fourth component is equal to 1 if IZ units are required to be affordable to low- or very low-income households; and the fifth component is equal to 1 if the program is mandatory. Exhibit 8 shows the positive relationship between the IZ tax and median per square foot house prices in 2017 among jurisdictions with mandatory or optional IZ programs.”

- “A second index, the IZ subsidy and flexibility index, measures five factors that either subsidize housing construction under IZ or reduce the cost to developers of complying with program requirements. The first component is equal to 1 if the maximum density bonus is greater than or equal to 20 percent (the median highest potential bonus across programs); the second component is equal to 1 if developers have the option to make a payment to the locality in lieu of providing IZ units; the third component is equal to 1 if IZ units may be provided off site; the fourth component is equal to 1 if the IZ requirement applies to only part of the locality; and the fifth component is equal to 1 if the IZ program is optional. Exhibit 9 shows the relationship between this index and median per-square-foot house prices in 2017 among jurisdictions with mandatory IZ programs. Again, the correlation is positive. IZ programs in more expensive jurisdictions tend to have more costly requirements to comply with and more factors that potentially offset these costs.”

- “The author uses a difference-in-difference study design and a two-way fixed-effects model to estimate the effect of IZ on new housing supply and prices by comparing the change in these outcome variables after jurisdictions adopt IZ to outcomes in jurisdictions that have not adopted it. Endogeneity is a potential identification problem in this research—if IZ correlates with higher market-rate housing prices, this correlation could be either because of an IZ tax that reduces new housing supply and drives up house prices or because localities adopt IZ programs in response to high and rising prices. To test whether localities adopt IZ in response to price spikes, the author uses a two-way fixed-effects model to estimate whether the years before a jurisdiction adopts an IZ program correspond with price increases … These findings are somewhat mixed but generally indicate that IZ does not seem to be implemented in response to large price spikes.”

- “Next, the author examines the effect of IZ programs on median per-square-foot prices at the permitting jurisdiction level. Because IZ can be expected to affect prices over time, with little or no effect on prices before its effect on new housing supply has had cumulative effects on the jurisdiction’s total housing stock, the author examines the relationship between the number of years a mandatory IZ program has been in effect and per-square-foot house prices … Column 1 in exhibit 14 shows the results of this basic specification. The author finds that each year of a mandatory IZ program can be expected to increase per-square-foot house prices by 1.1 percent, significant at the 1-percent level. In column 2, the author adds demographic controls, which reduces the coefficient of interest to 0.81 percent. The demographic controls are all small and insignificant.”

- “In column 3, the author moves to a spatial model. The “IZ tax” that increases prices in the jurisdiction that adopts it can also be expected to increase prices in nearby jurisdictions because real estate markets are competitive across borders. To account for this, the author uses a model with spatial lags … In this specification, the author finds that 1 additional year of a mandatory IZ program can be expected to increase per-square-foot home prices by 1.1 percent, indicating that the model represented in equation 2 may understate the effect of mandatory IZ on price. The spatial autocorrelation coefficient λ is not quite significant at the 10-percent level. In this specification, all the demographic controls are small and insignificant except for the natural log of median income, which is large, positive, and significant at the 5-percent level.”

- “The author turns now to the effects of IZ on new housing supply … Here, the author finds no evidence of mandatory IZ programs having an effect on new housing supply in the results of the cross-sectional models reported in columns 1 and 2. Column 3 uses the same spatial autoregression approach described in equation 3 for new housing supply rather than price. As in the cross-sectional models, the author finds no evidence that mandatory IZ reduces new building permits. Finally, the author tests the effect of IZ units delivered per 10,000 residents in jurisdiction j in year t on house price … The results of the cross-sectional models in columns 1 and 2 and the spatial model in column 3 indicate that, using this dependent variable as a proxy for a mandatory IZ program’s effect on market-rate prices, mandatory IZ does not affect price.”

- “The specification in equation 2, with the number of years a mandatory IZ program has been in place as the dependent variable of interest (results in exhibit 14), provides some support for Ellickson’s description of mandatory IZ as a tax on development. If mandatory IZ programs tax construction and result in reduced new-housing construction, their effect will increase over time as reduced housing construction year after year reduces a jurisdiction’s total housing supply relative to what it would have had without the IZ program. The results in exhibit 11 provide evidence that IZ is not adopted in response to rising prices, indicating that its effect on price is exogenous. Further, optional IZ programs (results in exhibit 15) that do not produce units have no effect on prices, indicating that these jurisdictions do not experience the same price increase as jurisdictions where IZ may tax new construction. The author’s empirical finding that, on average, mandatory IZ programs in the Baltimore-Washington region tax market-rate housing is supported by the lack of uptake of optional IZ programs with higher density bonuses than those offered under the region’s mandatory programs.”

- “The supply model in exhibit 17 provides evidence that IZ programs, proxied by the number of units they produce relative to their jurisdiction’s size, have no effect on new housing permits. A potential explanation for mandatory IZ increasing price—although not decreasing supply—is that IZ increases the cost of building new housing without reducing the quantity of construction. For example, IZ may lead developers to pursue more smaller projects. Smaller projects may allow them to avoid IZ requirements by staying below a unit threshold for each project. It may be less efficient to build smaller numbers of units in each project, resulting in higher prices without a reduction in total new supply. Alternatively, IZ may lead developers to shift to higher end housing that has the profit margins to cross-subsidize IZ units where lower end new construction may be infeasible under IZ requirements (Hamilton and Smith, 2012).”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice Podcast, I'm Shane Phillips. This episode we're joined by Dr. Emily Hamilton of the Mercatus. Center to talk about inclusionary zoning. inclusionary zoning is a policy or set of policies that requires developers to set aside a percentage of their units to low or moderate-income households at below-market prices. And Emily's research looks at how these policies have affected housing production and housing prices in the Washington DC, Maryland, Virginia region, the DMV. She finds that inclusionary zoning policies are associated with higher housing prices, and the effect grows larger, the longer an IZ program has been in place, but they're not associated with fewer housing permits. This is a bit of a puzzle begging the question of how places with IZ have ended up with higher prices, if reduced supply isn't the cause. Emily has a few ideas about why that might be, as do Mike and I. But I think it's fair to say that the jury's still out on the mechanism at play here. Beyond the research itself, we also take the opportunity in this interview to muse on some of the contradictions of iz. For one thing inclusionary zoning can only function properly in a context of exclusionary zoning. It's more of an appendage to exclusionary zoning than a solution to it. IZ and programs like it are also grounded in some very dubious analysis known as Nexus studies, which Mike and I spend perhaps a bit too much time ranting about. In any case, IZ is an important and increasingly universal housing policy across the US so this was an important conversation and we had a great time chatting with Emily about it. The housing voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Louis Center for Regional Policy Studies, and we receive production support from Claudia Bustamante and Olivia Irena. You can send feedback or show ideas to shanephillips@ucla.edu. And you can give us a five-star rating and a review at Apple podcasts or Spotify, and we hope you do. Okay, let's talk to Emily.

Dr. Emily Hamilton is a Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Urbanity Project at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, and she's here today to talk about inclusionary zoning. Emily, welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Emily Hamilton 2:31

Thanks so much for having me. It's great to talk with you.

Shane Phillips 2:34

And Mike Manville is my co host. Hey, Mike.

Michael Manville 2:36

Hey, Shane. Hey, Emily.

Shane Phillips 2:38

So first tour guide, what are your go to spots to take family and friends when they visit Washington DC? Or better yet, what would you take your planning and housing nerd friends to that you might not take other people?

Emily Hamilton 2:51

Sure, so a lot of people have had a chance to visit DC for one reason or another. So I'll try to give a few ideas that are a little bit off the beaten path. The first is Meridian Hill, aka Malcolm X Park in the Columbia Heights 16th Street Heights area of the city. It's one of my favorite neighborhood parks of all time, it's got these great walls, enclosing it has a very cool waterfall, little nice areas for sports or for just hanging out all kinds of different things - "city beautiful" style of park, done perfectly in my opinion. I would also go out to Eaton Center, which is not in DC. It's in Falls Church in the Seven Corners area of Virginia. It's a really cool, primarily Vietnamese shopping center with tons of really good fun spots, little grocery stores all kinds of Vietnamese and other types of Asian food out there, which in my opinion is the best food in DC especially if we're talking about food at relatively reasonable price points. And then lastly, I think the by far the best way to see the mall and the monuments is to go when it's starting to get dark and ride bikes around the mall. It's a lot faster than walking, which can be a bit of a schlep especially in the summer between these different monuments and there are some new bike lanes along the Mall so it's not as congested trying to navigate the sidewalks with pedestrians anymore.

Shane Phillips 4:38

I'm on board with any tour that involves getting around by bike. So the article we're discussing today is in Cityscape, and it's titled 'Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes. You're comparing outcomes and inclusionary housing programs in a bunch of jurisdictions in the DC Maryland Virginia region, which happens to be where inclusionary zoning or i z as we'll probably call it, a lot of times here was born. Let's start off by making sure we are all on the same page about what inclusionary zoning actually means. exclusionary zoning usually refers to things like zoning that allows only one house per parcel, or minimum lot size requirements, height restrictions, policies that cause us to build less housing, and which make the housing we do build more expensive, both of which results in higher rents and home prices. Someone might imagine that inclusionary zoning is the opposite of those things but it's really more of a tangential concept st best, I would say, what are people calling for when they advocate for inclusionary zoning policies?

Emily Hamilton 5:42

Yeah, so as you say, the term sounds like it's getting rid of exclusionary zoning. But what inclusionary zoning means, at least as I define it, as it's most commonly used in the Baltimore, Washington region, is a program that requires new developments of a certain number of units to include a certain percentage of below-market rate units. So for example, a new apartment building of 100 units might be required to have 10% of those units affordable to households that are making, say 80% of the region's median income. There's also a relatively prevalent, what I call optional inclusionary zoning approach in our region at least, and what that is, is when a local government will put on the books an option for developers to include below market rate units and a new project in exchange for the right to build, typically a larger building. Most mandatory inclusionary zoning programs, that first type where each new development of a certain size must include a certain percentage of below-market-rate units also have these density bonuses so it's kind of a Rube Goldberg way of planning because you have these mandatory affordability requirements with an automatic density bonus, rather than just changing the underlying zoning in these mandatory programs.

Shane Phillips 7:27

We'll just treat this as like mandatory versus voluntary, rather than get into you know, tying up zoning to the mandatory but between these two options, putting aside your research on this so far, but just kind of theoretically, what are the kind of perceived benefits and drawbacks of both of these approaches and maybe just of inclusionary zoning generally?

Emily Hamilton 7:49

I think the primary perceived benefit of both types of mandatory and optional inclusionary zoning approaches or voluntary inclusionary zoning approaches, is improving affordability for households earning below median income households at the lower end of the income spectrum are those that are suffering the most from really high rents and house prices across the US but particularly in coastal cities. So this is seen as a way to help some of those households, and it appears to be cost free. it's not requiring any outlay of public revenue. It doesn't require any difficult budgetary trade offs. So it seems like a way to improve housing affordability for nothing.

Shane Phillips 8:39

And comparing the mandatory to the voluntary like, why not just do mandatory if it is free, or if it seems to be free.

Emily Hamilton 8:48

There's, I would say relatively widespread concern among local officials who I've talked to about inclusionary zoning that these programs when they are mandatory, have real trade offs in the housing market. Local officials are often concerned that imposing a mandatory inclusionary zoning program will make it less feasible to build new housing in their jurisdictions. And they don't want to scare off development in many cases, perhaps sometimes they do actually want to scare off development and that's why they're implementing these programs. But we'll we'll assume benevolent policymakers here. And so they see optional or voluntary inclusionary zoning as a way to exchange increased density for below market rate units, perhaps without the effect of creating a tax on housing construction, or making projects that would be feasible without mandatory inclusionary zoning unfeasible.

Shane Phillips 9:57

I think it also be helpful to take a step back here and talk about the goals that IZ is trying to achieve. You mentioned providing below-market units to low-income households but people have different reasons for putting forward this policy proposal. On the one hand, you do have that perceived ability to just provide affordable housing, I think that's pretty clearly that does happen, you are getting some below-market units. On the other hand, you also have this goal of economic integration and possibly racial integration as a byproduct of that. And of course, you have plenty of people who advocate for IZ for both reasons on both grounds. Could you talk about maybe especially that since we've already covered the first one, maybe go into a little bit of more depth on that second, the integration aspect of this or the goal of this?

Emily Hamilton 10:44

Sure, so one of the well known outcomes of exclusionary zoning has been cementing in segregation along our race lines along income lines, as localities have zoned certain jurisdictions or certain neighborhoods as places where only expensive housing is feasible to build. So the typical, I guess, headline, exclusionary zoning regulation is often large lot zoning for single family housing only. So when localities implement those rules in a certain neighborhood or across maybe their whole town, they are shutting out people who can't afford that expensive housing, who are disproportionately people of color. So inclusionary zoning is seen as a way to remedy that to say that new housing construction in this locality is going to have a certain amount of below market rate housing that will be affordable to people who were previously shut out by exclusionary zoning. I do think that inclusionary zoning fails in a few important ways to achieve broad-based integration. However, oftentimes, we're talking about a very small number of units, and when we're looking at a neighborhood as a whole, that are going to be these below-market rate units. So we might get some integration at the building level but it's very rarely or never a policy for integrating a school district, for example, to a level that that we would find satisfactory.

Shane Phillips 12:29

Yeah, I think in a lot of neighborhoods, you know, when a city is growing, maybe 1%, a year, which is optimistic in many cities, and maybe a neighborhood is growing about the same amount. So in five years, they've added 5% of their housing stock, and 10% of that might be below market. And although not all of those units will be you know, people of color, it's you can see how it doesn't add up too much.

Emily Hamilton 12:52

Exactly, and when we're talking about the Baltimore-Washington region in particular, we're a very high-income region, and many of the inclusionary zoning programs in the region target households making say 80% of the area's median income. And so that's not 80% of the median income in the DC region is not a household in poverty, not the households that we are often most concerned about having access to adequate housing.

Shane Phillips 13:26

So one concern with IZ, even when it's optional, and incentives like density bonuses are provided, is that it depends on restrictive zoning to work. If a city changes its zoning, so that suddenly developers can build 12 or 20 unit buildings on most parcels in the city, which would be a very great thing to happen, and it isn't really proposed in many places. But if that were to happen, there's probably no longer any incentive to set aside units at below-market prices because there's no real need to get that extra density or floor area, there's plenty of places to build and building that 12 or 20-storey or 20 unit building is plenty. So in other words, for density bonuses to work, you have to keep the zoning at densities below what the demand for housing would otherwise dictate. And in the case of mandatory programs, you need rents or sales prices in market-rate units to be high enough that they can cross-subsidize the below-market ones because those are being built and run at a loss. So you keep the market prices high by limiting the supply of housing, and really in that case, the incentives are very similar to the voluntary situation. So this is going to be also a question for Mike since it relates to his work on pretextual zoning and value capture but I'd love to hear both of you opine on this a bit. I'll start with my own comment here, which is that inclusionary zoning requirements, effectively raise the floor on the price that you need to rent or sell market rate homes for in order to earn a profit. That means if a jurisdiction actually succeeds at lowering prices and a comp prehensive way, new market rate homes won't earn enough profits to cross subsidize those below market homes, and homebuilding will grind to a halt. Emily, you make this point in the last paragraph of your article, but the awkward truth is that inclusionary zoning can only succeed in the context of exclusionary zoning. If you get rid of exclusionary zoning, it no longer works.

Emily Hamilton 15:23

That's exactly right, and that's why I am not optimistic for inclusionary zoning ever being a path toward broad-based housing affordability. Because if we're in an imaginary world where homebuilders and developers can provide as much housing as the market will pay for, we are in a world where density bonuses don't have value, and inclusionary zoning requirements are a clear tax on housing construction, with no offset. Mike, you want to talk about your work on this topic.

Michael Manville 15:58

Yeah, I think that, you know, I agree with everything both of you just said. I think you know, and I've written as much in a couple of places that a lot of the value of inclusionary zoning comes from, it's sort of symbolic or performative aspects, that Emily alluded to the idea that one benefit of inclusionary zoning is that it doesn't demand any money, or it doesn't seem to right, you know - this will come from the developer. So the city and therefore its residents don't have to pay more in taxes to get affordable housing. It also doesn't demand much realistically in terms of changing neighborhoods, right, because you know, what we've talked about so far on the one hand is very true is that there's some inclusionary zoning programs that from the developers perspective are optional. But the other thing is that it's always optional from the localities perspective, right, that, you know, to go all the way back to what Shane said earlier, if you're a classic exclusionary city, you know, nothing but detached single-family homes, well, inclusionary zoning is not going to do anything about that unless you adopt an inclusionary ordinance. And then even if you do adopt an inclusionary ordinance, as Emily pointed out, normally, there's some size threshold. So you can adopt that threshold and say, "okay, well, if you build more than 20 units, you have to set aside 10%" but if 3% of your parcels are zoned for that, you know, most neighborhoods will never change. And so I think one of the great advantages politically of inclusionary zoning is that if you're in the type of city we have, right now, that's very expensive, which is a sort of coastal city with liberal or democratic minded people who, on some level care about affordability, but then on some level, like the way their neighborhood looks, and would rather not spend a bunch of tax money because they already have probably pretty high taxes. What inclusionary zoning does is it sort of resolves their cognitive dissonance, you know, it says like, "okay, well, we're gonna, we're gonna make sure the developer takes care of these low-income people but somehow, even though we're doing that, your neighborhood won't change and your tax bill won't change", and it is, you know, it's sort of, and I'll stop getting on my soapbox too a little bit, but it really is kind of an outsourcing of the welfare state in many ways, right. This is a function that there was a time when there was broad based concern among liberal-minded people like me, like, well, you know, it's a housing subsidy, this is something everybody pays into, and we have a program that does it. And now it's something that we just rely on some constrained private actors to kind of make a half hearted attempt at. And so for that reason, I share Emily's skepticism that this will ever get us a lot of housing, and then I become extra cynical, and I wonder if that was ever really the goal?

Shane Phillips 18:45

Yeah, I do feel like, you know, when you have 30, or 50% of your renters, or at least low income renters who are paying half of their income on rent, and you look at the scale of these programs, when you're building again, you know, maybe 1% of your housing stock growth per year, somehow you're trying to solve an entire housing problem off of that 1% growth. It's just like, mathematically, it clearly doesn't work, and I don't think we're always very honest about that.

Michael Manville 19:14

Yeah, and I think to go back to something the two of you chatted about a few minutes ago, you know, one of the things that makes, you know, potentially inclusionary zoning unique is this idea of building-level integration right - that you would you would have people have different incomes, and thus, perhaps have different races or ethnicities occupying the same building. But one thing that I think is lacking from that argument, is really a clear justification that that is a really important level of integration right, as opposed to the school district as opposed to the, you know, the public safety district or something like that. And it's not to say that you can't imagine benefits at the building level happening, because you could, but to say that if doing that means we get so much less housing than, you know, sort of big project level efforts to integrate a school district, it's not clear that it's worth the trade offs, and someone could argue with me about that, for sure but I think that the main point is that you almost never hear that discussion.

Shane Phillips 20:12

Yeah, I can certainly imagine it having an impact but I do think part of it probably comes from the reality that at a building level, you can, in many cases require 10, or 15%, or maybe even 20% of the units to be for below market households, that's a significant percent. Doing that even on every new building that's built isn't going to get you anywhere near 10%. below market, right in the entire neighborhood or in the entire city. And so it feels like you're accomplishing more, even though maybe not so much, Emily, let's start to get into some of your actual analysis and results from this paper. In your article, you're evaluating the inclusionary zoning programs in the Baltimore-Washington DC region that includes the first IZ program in the country passed in Fairfax County in 1971 though that one was struck down by the Virginia Supreme Court, and they had to come back later, after some state reforms. It also includes Montgomery County's program in Maryland, which is arguably the most successful IZ program in the nation, in addition to a whole bunch of other cities and counties and area that have their own programs and some which do not. Montgomery county and Prince George's County, both in Maryland stand out for their annual production. I will note that Prince George's doesn't have an IZ program anymore, but when it did, it did produce a lot of houses both actually produced more than 300 below-market homes each year from their IZ programs, while in all the other cities in your analysis, the remaining dozen or so jurisdictions produce fewer than 100 below market units per year. What do you think accounts for such large discrepancies other than, you know, maybe just put differences in population?

Emily Hamilton 21:55

Yeah, certainly worth pointing out that both of those are large jurisdictions in terms of population so that's part of it. I would love to know more about the inclusionary zoning program that was in effect in Prince George's County. It was implemented for a period of a few years in the 1990s, and did seem to produce a large number of units in each of those years when it was in effect. Unfortunately, I haven't been able to track down anyone who was working in planning back then in Prince George's County to learn more about if there were specific projects that were specifically approved because of this program being in place that helped lead to its success in terms of delivering units. I only know what others have written about it decades ago, unfortunately,

Shane Phillips 22:48

Do you happen to know why they got rid of it, or like it was very successful, and they're like, "Ah, maybe we don't want to keep doing this" or, you know, "we built enough affordable housing, we could stop now" like what happened?

Emily Hamilton 23:01

It kind of seems like that might be the case. Policymakers from Prince George's County said we already have more than our share of the region's relatively affordable housing, which is true - it's a relatively low income, I believe it's a majority black County, and so I can see why they didn't feel that it was their responsibility to provide even disproportionately more of the region's relatively affordable housing.

Michael Manville 23:32

And that goes back to I think, the point we're making just a moment ago, which is that when you have these policies, but you simultaneously have an uneven distribution of where multifamily housing goes, right, and if that multifamily housing tends to go in places that are not the most affluent, well, then your affordable housing goes in those places, too. You know, it's just sort of like Los Angeles did have a mandatory inclusionary zoning program for a bit of time, and then a lawsuit got rid of it about 10 years ago but you know, during that time, again, like 25% of LA's residential land is zoned to hold apartments. So huge swaths of the city were just never going to get affordable units and affordable units that were produced are going to be concentrated in places that again, because of the zoning, already had most of the affordable units. And you know, in a perfect world, we'd all be pretty welcoming of affordable housing, but we all know that, like people do start to resent it. And so you know, if that's what played out in Prince George's County, it certainly would not be it might be a disappointment, but it wouldn't be a surprise.

Shane Phillips 24:35

Yeah, I mean, here in LA, you hear councilmembers say, like, I've built so much affordable housing in my district. We need to do it somewhere else now, that kind of thing. And I think even that inclusionary zoning ordinance that was in Los Angeles was only in the Central City West neighborhood, one of our 35 community plan areas and a pretty poor area, kind of Westlake MacArthur Park area, and so again, it kind of mirrors that same trend. So I didn't really give you the chance to finish in terms of like the differences, Emily, between these different places like why do we think some have been effective and others have not?

Emily Hamilton 25:12

Yeah, so as you said, Montgomery County is often pointed to as the Gold Star inclusionary zoning program. It's produced more than half of the region's entire stock of inclusionary zoning units. I think one reason that it's produced so many units is because it's applied by the book - each project that is proposed in Montgomery County that looks like it should require a certain amount of below-market-rate units, in fact, has to meet those requirements. In the city of Baltimore, in contrast, there is a an inclusionary zoning program that is mandatory, it's on the books as a straight requirement. But if developers can show the city that their project would be infeasible to build, because of the inclusionary zoning units, they can get a waiver for it, I don't think Montgomery County really engages in any of that so that's why it's produced a lot of units. And this issue is also something that makes inclusionary zoning really difficult to study econometricly, for example, because we can't see what the effects of a program are based on just looking at their rules. And this is true of zoning across the board, so many localities engage in the level of discretionary permitting that Mike has talked about, that just makes it really difficult to look at a zoning ordinance and understand how friendly or unfriendly locality might be to new development.

Michael Manville 26:59

Yeah, I think that's a great point that's going to kind of foreshadow, you know, a bit of our discussion of your results. And I think it's worth emphasizing, as you just did that, it's something that comes up with all these local ordinances, in part because the same law sometimes conceals different motivations. You know, Baltimore just might want something that's going to bring developers to the table, bend the knee, and then a council member or planner can say like, well, in this particular instance, what we actually need from you is a contribution to this playground, not affordable housing, whereas Montgomery County might just be like, we want you to build affordable units. Well, those two laws can be written identically, but actually be aimed at very different outcomes. There's no way to know that once you put it in a reset a regression. And then of course, on top of that, is just that no two laws really are written the same, right? You know, and I think this comes up as well, when we study rent control, which is like, you know, yeah, there's a bunch of different cities that have rent control ordinances, but the devil is always in the details. And so what actually binds and what, you know, what really forces someone's hand, either on the developer or the city side, varies a lot, and it's hard to sort of collapse that into a single number. And so I think that these are the type of empirical exercise you've engaged with here is a very challenging one for that reason.

Shane Phillips 28:17

Yeah, it is hard to collapse into a single number, and yet, Emily did her best right?

Michael Manville 28:24

You know, it's better to try than not try it, and then just be honest about the caveats. I mean, that this is the business we're in.

Shane Phillips 28:30

So yeah, it's a good transition because one real challenge for comparing these icy programs across jurisdictions is just how much they vary, both in terms of what they require, and what bonuses they offer when they offer them or if they offer them. That can be, you know, requirements, varying in terms of the minimum share of below-market units or share of units that have to be for below-market households, and the affordability level of those below-market units because it costs much more to provide a unit that is affordable to an extremely low-income household than a low income or a moderate income household. And the bonuses ranged from density to height to floor area to many other things, no model can capture all of that variation perfectly but you did make a very valiant effort to group these IZ programs by how strict they were in terms of requirements and how generous they were in terms of bonuses. Could you tell us a bit about that process and some of the challenges of trying to score each of these jurisdictions?

Emily Hamilton 29:28

Sure, I created an index that tries to collapse the tax of inclusionary zoning so that tax includes the percentage of units that have to be below market rate, the extent to which the households in those below market rate units have to be earning below median income, and then the subsidy that is intended to offset these taxes so the size of the density bonus being the primary one. And I think that's kind of an exercise in trying to get a handle on how much any of these programs are going to affect market outcomes. But certainly not an exact method, we can by looking at the requirements across all of these jurisdictions get an idea of which ones are the clearest taxes. So for example, Howard County, Maryland is the only jurisdiction in this region that has a mandatory inclusionary zoning program with no density offset, so that one's we can say, as long as it's enforced to some degree, that one's definitely a tax on housing construction.

Shane Phillips 30:48

And that's the bonus projects, on the other hand might be you're actually earning more profit, potentially, by taking advantage of those incentives, or what have you, you know, you can build 30% more market rate units, and you only have to provide, you know, five or 10% of the units in the building for below market households, that might actually be a more profitable project than just building the baseline density with no below market units.

Emily Hamilton 31:12

Exactly.

Shane Phillips 31:13

So you were interested in how these scores correlated with housing price in each jurisdiction specifically the median price per square foot, what did you find there?

Emily Hamilton 31:23

So I find a slight positive correlation between the size of the the IZ tax and the per square foot house price, but it's certainly not a very strong correlation, I wouldn't want to make anything like a causal claim based on that alone.

Michael Manville 31:44

And I think, you know, one, one question that, you know, comes to mind and will probably come up again, as we talked about your regressions to is just the advantages and disadvantages of using the price per square foot as this dependent variable of interest. You know, I think, on the one hand, obviously, houses come in all different sizes, and it's important to normalize, right? You know, it would be, there are real disadvantages to just saying, like, the single-family home costs more than this apartment and not accounting for the fact that one's a single-family home and wants an apartment. On the other hand, there is the fact that like, from the consumer side, right, we tend to purchase the unit rather than a sort of aggregate of square feet you know, the classic, if you read the New York Times, and these obnoxious articles about people hunting for real estate, like, they had $500,000, what could they get? And it was just like, well you get the best thing you can get for $500,000. Part of that's going to be square footage, but it's also these other trade offs, and then I think the third thing that came to mind when I was reading your paper was just that a lot of what is going to be built or be deterred from being built as a result of an inclusionary ordinance will be housing that would be rented, right? And so of course, sales price is a sort of a combination of current rents and expectations, whereas rent is really the current consumption value. And so I wonder if you could just talk a little bit about, you know, what, what sort of went through your head when you were kind of weighing these different variables?

Emily Hamilton 33:13

Yeah, that's a great question, and I can definitely see arguments for using a different dependent variable than per-square-foot prices, or the log of per-square-foot prices. The reason I settled on that is because when we think about inclusionary zoning affects, it's often on the option value of land. So inclusionary zoning has an effect on housing markets by determining, for example, whether or not it might be feasible to redevelop a given parcel. And I think that will be most visible in prices, of course, rather than rents, although inclusionary zoning could certainly have effects on market rate rents, in one direction or the other. The other challenge with rents is when we have an inclusionary zoning program in place, we're seeing its effects on market-rate rents, as well as below-market-rate rents. When we're we're often only looking at the average. Now there are inclusionary zoning programs that apply to owner-occupied housing as well, which creates this same mishmash in the median price of a jurisdiction between its below-market-rate units and its market-rate units, but in general, there are much fewer owner-occupied inclusionary zoning units, so I think it's less of a problem. And then as far as why I used a per-square-foot price, rather than just a price. Again, I can certainly see an argument for using just straight price instead but I used the per square foot price because what is getting built in some of these jurisdictions has changed a lot over time. So for example, in the early years of my study, Loudoun County, Virginia was, by and large, single-family houses on very large lots with a little variation from that. During the period of my study, it's seen lots of townhouse construction, which is going to be a lot smaller size of house that people have the option to buy out there. Similarly, Arlington County saw a lot of construction during this time period, almost exclusively of multifamily housing. So it's probably seen its median unit getting quite a bit smaller over time.

Shane Phillips 35:56

And one other complication here is that smaller units tend to have higher per square foot costs for a variety of reasons. But one of them is just that, you know, a larger share of the unit is kitchen and bathroom, the things that cost the most to build in a home. And so all of these things, they might actually kind of bias your results.

Michael Manville 36:16

Well, it's important, it's important to draw a distinction between prices and costs, right? I mean, the developers cost to build and then the person's price to consume. I mean, there's a correlation. But I think your point is true, Shane, even with prices, just because, you know, oftentimes you don't see smaller units until you see high land values right. And this goes back to if price per square foot was just the real metric of affordability, then it would be more affordable to live in Westchester County than in the Bronx, right? But of course, it's not true, the Bronx is much higher prices per square foot, but because they have those they build smaller units, and why people move to Westchester is that they take advantage of lower prices per square foot to consume huge houses. And so it's, you know, it's again, I'm a regression guy too, it's just, you know, we have to be mindful of all the things that when we make these decisions, we get some stuff and we lose some stuff.

Emily Hamilton 37:10

Definitely!

Shane Phillips 37:11

And yeah, and I think it's I think it's worth emphasizing here that this is not criticism, this is just like more for our audience's benefit to understand that there is no perfect way to measure these things, and you just have to make a choice. And you have to understand why you made the choice and what those trade offs were, and so hopefully, we've made those trade-offs a little clearer here.

Michael Manville 37:29

Yeah, all these comments can be applied to all of my papers as well.

Shane Phillips 37:36

Okay, so the major findings of the article are in the regressions, and there you found that having an inclusionary zoning program was associated with housing prices increasing at a faster rate than places without inclusionary zoning programs, but not a reduction in new housing permits. Starting with the association between prices and an IZ, how big are the effects we're talking about here?

Emily Hamilton 38:01

So again, another debatable choice that I made is using the number of years that a mandatory inclusionary zoning program has been in place as the variable of interest. And I made that decision, because we don't expect a program that's been in effect for just one year, for example, to have much of an effect on market outcomes, because any amount of change to the housing stock that might happen in that one year is going to be very small.

Shane Phillips 38:36

It might reduce permits pretty quickly, new construction, but you wouldn't expect that to affect prices all that much, because it just takes time for you know shortage of housing to kind of have that effect on prices. Is that essentially what you're getting?

Emily Hamilton 38:50

Exactly.

Shane Phillips 38:51

Yeah. Okay.

Emily Hamilton 38:52

And so what I find is that each year, a mandatory inclusionary zoning program is in place, localities have experienced about a 1% increase in their median price per square foot relative to what they might have expected without that program being in place. And as you pointed out in our earlier exchange, that's a big effect over time because that's a compounding effect on the median per-square-foot price.

Shane Phillips 39:26

And how about on housing permits?

Emily Hamilton 39:29

I found no effect. And there have been other studies of inclusionary zoning that have similarly found that these mandatory programs have increased prices without an observable decrease in the amount of housing that's being permitted. And that's definitely a puzzle because we think that the the channel through which inclusionary zoning might lead to higher market rate prices is by reducing the amount of housing that's feasible to build. So without that supply effect being observable, what's causing this increase in price?

Shane Phillips 40:09

And you do you know, in your literature review that, as you say, this is not a totally new finding, Antonio Bento and his co authors also found that prices went up in jurisdictions with IZ but housing starts didn't slow down. Jian Guo and Fei Li found that changes to the IZ law in London caused development to shift towards smaller projects not subject to their new rules but it didn't reduce supply overall. There's also research out there that does find a negative impact to supply so I don't want to imply that yours is a universal finding. But I do really find it surprising how common this specific finding is that prices go up but supply does not change. What do you attribute that to? You know, as you say, wouldn't we expect higher development costs to either reduce the turnover of developable land that option value that you were talking about, or require more expensive market-rate units, either of which would result in reduced supply? I was wondering if this maybe has something to do with because so little housing has been allowed because it's so constrained in cities relative to demand, that IZ maybe just like isn't the binding constraint here?

Emily Hamilton 41:19

Yeah, potentially, um, when social scientists talk to developers about how they respond to inclusionary zoning, they often say that it leads only the fanciest highest-end developments to go forward. So perhaps if we take them at their word, it's causing a shift toward fancier new housing, raising median prices somewhat through that channel. But I don't think that really makes sense because why wouldn't they just build that fancier housing if it's more profitable to begin with whether or not the inclusionary zoning program is in place but that's one possibility. I think another possibility is that it leads developers to shift to smaller projects. In Portland, Oregon, for example, it certainly seems that has been the case there; developers have shifted to building multifamily projects that come in under the size threshold that triggers the inclusionary zoning requirements. And so perhaps through that channel, it raises the cost of building and raises prices but we still see the same number of units getting permitted. I definitely think it's important to keep in mind that we're not observing anything like a free market, where developers build until the marginal revenue of building an additional unit exceeds the marginal cost. We're very much in a world where local governments are deciding how much housing they're going to permit each year, and so perhaps the inclusionary zoning program is just not going to have an effect on that number, and they're going to permit how much they're going to permit, and that's how much will get built. We definitely saw that type of thinking at play in Washington, DC, I think, where there was a big study about how much housing was getting built after the city implemented its inclusionary zoning requirement, and policymakers saw that, in fact, the rate of permitting did not go down after the inclusionary zoning program was implemented. It in fact, went up. And they decided to basically increase the stringency of the inclusionary zoning program as a result of that study and began requiring developers to provide below-market rate units to lower-income households than they previously required.

Shane Phillips 44:05

I'd be curious, you know, the link between proposed units and permitted units, you can imagine, you know, a city has the planners and the permit checkers at the building department that it has, and if they're already at capacity, and they're kind of the bottleneck in terms of processing permits and entitlements, then if you impose this additional cost, maybe the proposed units falls, but it's still more than the planners and the building department officials can actually process in a given year so you wouldn't actually observe a difference in permitting. But then there's still the question of like, well, why then is our prices higher?

Michael Manville 44:50

Yeah, I mean, I think there's a couple of things going on here. One, again, is that I think this is an area where having the prices per square foot, it could show some things and conceal some things, right. I mean, it's sort of, you might see something different with a rent measure or a price measure. But I think, for the most part, the explanations Emily ventured were the ones that occurred to me as well, that one is just, there's going to be noise, right? The kind of city that has an inclusionary zoning program also is fundamentally restrictive city, as you pointed out earlier, otherwise, inclusionary just doesn't work. And probably a lot of its neighboring cities are too. And also, if you think that some of these mechanisms spill over, you know, that can sort of send the regression results in different directions. But I think the big one really is, and this rose up in conversations I've had with developers, and certainly, with Shane and I and our work we've done on the transit-oriented communities project, which is a sort of optional inclusionary program. In Los Angeles, we see this too, which is that when you go to participate in one of these programs, there's an inescapable understanding that the units you build that are market rate have to pay for themselves, and then help pay for a subset of other units in your building. And that means that, you know, a developer can't make the market, right, but whatever the market is, you're probably going to have to build a lot of those units to the top of that market. And it's possible that that's not something you would have done before, because it's not always is that a misunderstanding people have, it's not always the most profitable thing to build to the top of the market. You know, Walmart has made a lot of money building to like the lower end of the market. And Toyota has made a lot of money building Corolla as they go to the middle of the market. But if you really need to have a high margin, right, and that's what you need, if what you're signing up for is like, "okay, for the next 30 or 50 years, your market rate units are gonna carry these below market rate units, well, then what you build has to be expensive, and that can be a function of size. And certainly, that may be what happens with Portland, right, where you say, like, "Oh, we have this parcel, and we could have built 15 units on it but we don't want to trigger inclusionary so we're going to build nine". Well, guess what now they are bigger, it could be more parking, it could be the kind of things you do just to try and get that rent premium, whether it's more windows or what have you but you're gonna build higher priced stuff, and then over time, that nudges the medianup even if if you aggregate over the entire city, you have roughly the same number of units. So I do think it's still a puzzle, and someone can certainly argue with that but that's the most persuasive explanation to me.

Yeah, I think I agree!

Shane Phillips 47:44

So I think we're, you know, we all came into this, and we're all kind of we knew where we stood on this a little bit already. I think that ice doesn't accomplish a whole lot, and it has some real downsides and trade-offs. But then the question, of course, is, well, if it's not this, what are we going to do instead? And I know, Emily, you've given a lot of thought to this, if we want to provide below-market units on the one hand, but also just have a more affordable housing market generally. And also, you know, really importantly, actually achieve economic and racial integration. What kind of policies should we be looking at instead of inclusionary zoning to achieve those things?

Emily Hamilton 48:24

Well, I think first and foremost, the remedy for exclusionary zoning is repealing exclusionary zoning, not creating these really complex regulatory webs to try to maintain exclusionary zoning while getting rid of its problems. So every local government across the US can make improvements toward getting rid of exclusionary zoning - things like reducing their minimum lot size requirements, expanding the areas where multifamily housing is permitted, reducing parking requirements so that's the right way to address the many and varied problems of exclusionary zoning. To the issue of providing below-market-rate units or some other types of subsidies for low-income households who may not be able to afford adequate market-rate housing regardless of the zoning environment. My first best policy choice would be simply number one, reforming the zoning rules, number two, expanding federal housing choice vouchers to cover many more households particularly starting with those at the bottom end of the income distribution. Now, I think proponents of inclusionary zoning will say well, that's not going to happen anytime soon so we have to do inclusionary zoning in the meantime. Point well taken I certainly can't waive any sort of have a wand to bring that World about, I think the approach to achieving the objectives of inclusionary zoning without running the risks of potentially reducing housing construction or increasing market rate housing prices, is an idea that I've gotten from David Schleicher, who's written about tax increment local transfers. And the idea of this concept is that when a locality upzones a single parcel, or a small area, increasing for example, the amount of apartments that can be built on that site, they're going to be increasing their property tax base by increasing the land value of that small area. And if that leads to development, then they'll be also increasing the value of the building on that site. And the amount of that increase in the property tax base is called the tax increment, and locality could conceivably use all are part of that tax increment, or the increase in property tax revenue that they get from that up zoning to subsidize housing within that small area, or across the city as a whole however they wanted to structure it. And by using the revenue that comes from upzoning to subsidize housing, rather than requiring the people who are building housing to subsidize housing, I think they can get the flavor of the intended outcomes of inclusionary zoning, without potentially making things worse for everyone who doesn't get to benefit from the small number of below-market-rate units.

Shane Phillips 51:53

And in a sense, it's still I realized, this isn't ideal for us. But it's, it's still kind of maintaining exclusionary zoning in a way, because if you're just zoning a small area, and I brought up zoning, Building up the Zoning Buffer paper, if you just stepped down in a small area, it does tend to increase the land values by quite a bit. If you were just to, you know, if not abolish zoning, very much liberalize it and allow a lot higher density and taller buildings city-wide suddenly no individual parcel is all that valuable, and so you probably wouldn't see a lot of gains to land value and therefore tax increment from that. But to the extent that we continue doing this approach, if we're going to just assume part of a neighborhood or this corridor, I could definitely see how that would work.

Emily Hamilton 52:36

Yeah, that's right. I think it would allow some of the, well, perhaps it's more politically realistic to think that a city might choose this approach to up zoning small areas and using some of its increased revenue for subsidizing housing, rather than abolishing exclusionary zoning, for example.

Michael Manville 53:00

Yeah, I mean, people often do say, "look, you know, this is all we can get politically", and that may be true, but also, it's dissatisfying for that to end the argument, because I think that when people say that they should meditate on what that means, right, which is that like, you know, fundamentally, we're just so much more conservative about housing than we are about almost anything else. I mean, like, you know, I'll steal the line from Edward Glaeser, like, who would never think it was a good idea to just have farmers solely fund the food stamp program, right? We would understand that that would just deliver so little food assistance, and would probably be perverse. And so if you say like, "oh, okay, well, you know, this is all we can do", I mean, my response to that is like, I don't believe that. And, so like I mean, because most people who say things like that, you know, they want an equitable outcome, but they generally in most other areas, understand that like, well, if you really want this, we do have to spend some money. And we would have to spend a lot less money if we also, you know, as both of you pointed out, actually got rid of exclusionary zoning, I mean, one of the biggest costs of inclusionary zoning comes from the fact that regardless of its actual impact on the housing supply, which I think you know, as we've discussed, is empirically, really hard to measure, is that it just doesn't make sense, right? And it's not a good thing to have very prominent government policies that just don't make sense, and if you just imagine the sort of sequence of conversation where you actually tried to explain inclusionary zoning to a 10-year-old or something, you just say like, "well, the problem is that like, most of the places around here don't allow apartments". Okay, well, the solution is then to allow apartments, "no, no, it's to take those small number of places that do allow apartments and make them have some apartments that cost a little less". Like well, okay, well, there's benefits to that, but like, it seems like you're just avoiding the problem.

Emily Hamilton 54:53

Yeah

Michael Manville 54:54

And I think one more thing that I would love to hear Emily's thoughts on is just that, because it's a pet peeve of mine, and I want to be validated, is that you can't have these laws on the books, right, without some mechanism, like what planners would call a nexus, saying why you think they should be there. And those nexi, is that the plural of Nexus is?

Shane Phillips 55:19

Yes, nexi

Michael Manville 55:20

Those things, they really don't make sense, and there's real costs to having them because, you know, a story I like to tell, I was with our colleague, Paavoo Monkkenn, and this was years ago now in a city council members office, and we were talking about, you know, just trying to get some more building in Los Angeles. And the deputy for this council member who has dealt with Planning and Housing said, "well, you know, I mean, one thing we have to keep in mind, you know, we just had our nexus study come out so now we know, actually, when you build more housing, it makes housing less affordable", and Pavo, admirably kept the straight face and mind. But I mean, there are real cost to this even if it doesn't sort of actively reduce the supply of housing, because what you've done is you've actually put in your city's laws, a conclusion that says, you know, building more housing causes a lot of problems, affordability problems, and now we have to mitigate that.

Emily Hamilton 56:22

Yes, I emphatically agree the constitutionality of inclusionary zoning rests upon there being a nexus between new housing construction, making housing more expensive, which is just not the case. We can know from very basic economic theory, we can observe the localities across the US that build more in response to demand increases, relative to those that don't...

Shane Phillips 57:03

And just intuitively, like what a disaster would it be, if by trying to give people homes when they have children and you know, form new households and move places like, somehow everything is getting worse. We wouldn't have survived as a species this long, you know, of housing crisis, every home would cost a billion dollars.

Michael Manville 57:22

You know, and I just want to put a bit of a point on this. The concern about inclusionary driving up prices, which is I think, in Emily's paper really drives this point, you know, makes this point very clearly, it's a real concern. And the concern that it reduces supply is a real concern. But if you look at Nexus studies, that concern has come to be the conversation about inclusionary which is, again, understandable. So if you look at the Nexus study that Los Angeles did for its linkage fee, you know, I'm gonna get these numbers wrong, but it's easily 200 pages. And the vast majority of that is a series of calculations done with pro formas, and so forth, saying like, "well, this is the fee that hits that sweet spot between we close the gap between what an affordable developer could raise and what they need, and it's just low enough so that it will deter housing construction". But that's not a Nexus, that's just saying, like, "hey, we can do this, and they could pay for it". The Nexus, which is the argument that says when you build this market-rate housing you actually create affordability problems, It's a paragraph right? I mean, it's sort of the empirical question of what this will do to the development market and to prices, has completely swallowed the constitutional demand to show that actually, one of these things causes the other, and you know, LA's Nexus study is going to be a little bit too unkind - it's a global search and replace of like the kind of Nexus study that's done all over California, right, but there's nothing unique about it. And what we've arrived at a point where the Nexus is now an assumption and not a burden. The burden is now to show that it will reduce housing construction but you know, it really is, if you just step back and say like, okay, well, let's just suppose all the developers can afford it, this is still just a really weird policy.

Shane Phillips 59:20

I do want to like spell out that Nexus as they describe it a little further, because I do think it's important, and it's sort of a hobby horse of mine to take this down constantly whenever it comes up. But the idea is, you build these market-rate homes, it attracts somehow high-income people, those high-income people, they get their hair done, they go grocery shopping, they need all these services and goods that are mostly produced by people who are middle-income, lower income, and therefore they're generating this demand by simply existing for low income housing. And so we're going to you know, capture some of the profits or redirect or whatever, to fund those units. And there's never any kind of grappling with, well, do those market-rate units actually attract people who wouldn't have been here otherwise, and like evidence suggests not really, because the share of people who have moved in the last year that live in new housing versus older housing is pretty much exactly the same no matter where you go, indicating that people, you know, and you just think about this logically, like, I think we've all moved at least once in our lives, we didn't look around the country, like who's got the new market rate housing that I really want to live in. Like, we found a job or we got accepted to a school, and then after we've made the decision to move, we started looking for housing. And if all of the housing was too expensive, then we might not have chosen to go there but certainly, the presence of market-rate housing is not attracting anyone, and if they can afford market-rate housing, new housing, then they can afford older housing, almost by definition, and so they're the last to be deterred by the lack of market-rate housing. Also, I'm so sorry, I'm just going off here. But like, the idea that, you know, the jobs generated by these "high-income people" are also attracting low-income workers, rather than giving people who already live in the region jobs. None of it makes any sense. Sorry, I'll stop.

Michael Manville 1:01:35

I think you're right, and I think the thing I like to say about it, too, is that if all it took to attract high-spending yuppies was some new housing, you know, we would have no declining cities. Someone tell Milwaukee or Rochester right that they just need some condo towers, and then it's, you know, here come the high-income people, and they're gonna pull in the low-income workers and no developer would ever build in San Francisco - you could just buy cheap land somewhere, and, and mint a fortune by, you know, the person attracting properties of your new housing. And so the Nexus studies really are silly. I mean, the other explanation that sometimes given for inclusionary zoning is the amenity effect of a new housing unit, that it just raises rents around, you know, and I don't want to totally neglect this idea that like, "oh, you put up a fancy new building suddenly the neighborhood's nicer, and so rents go up around it." I think very quickly, you can just say, empirically, it seems like the opposite is true that the supply effects swamps, the amenity effect, but even if it's not, you have these two additional considerations which come to mind, which is like if you take the amenity argument seriously, then it is not just new developers who should be providing affordable units, right, it's anyone who provides an amenity. And so like a new housing development might make a neighborhood more attractive, but certainly a new park does, certainly lower crime does certainly more trees do. And then even if you set that aside, then it just becomes this question of if the concern really is rising rents and existing buildings nearby, it's not obvious that inclusionary housing helps that, right? And when you have this sort of ecological problem where it's like, "oh, we put some affordable units in this neighborhood that people are being forced out of". But of course, if the people being forced out don't get in those units, then you've sort of preserved affordability on average right but like, that's not much of a policy goal, if you're the person being forced out of your building, right? He was like, Uh, sorry, you have to go. But like, you know, what the average stays to say. I mean if you really believe that's the problem than what you would say, and to be clear, I don't think this mechanism holds up, but if you do, then every time that neighborhood gets nicer, someone should actually make a payment to existing renters right, not just build some affordable units. So I think top to bottom, it's a kind of an affront to basic logic, and I understand why we have it, but it's for those of us who really do worry about housing affordability, I think it's such a disappointing set of policies.

Shane Phillips 1:04:11

Emily, thank you for sticking around as we just like to hear to rant about all of this.

Emily Hamilton 1:04:18

No, I will love to rant about Nexus studies any day.

Michael Manville 1:04:23

Most of our episodes don't end with Shane and I just complaining.

Shane Phillips 1:04:29

I think one of the last ones was the value capture, which is a very simple topic, so you can see where our loyalties lie.

Michael Manville 1:04:33

Maybe the problem is me

Shane Phillips 1:04:37

But Emily, you're a very prolific writer and researcher. What else are you working on? Where can people find you if they want to keep track of what you're doing?

Emily Hamilton 1:04:46

People can find what I'm working on and thinking about on Twitter, my handles EBWHamilton. Right now. I am studying the effects of Houston's 2013 minimum lot size reform outside the city's i610 loop, which is like the uh...

Shane Phillips 1:05:08

sort of a follow up to Nolan's work?

Emily Hamilton 1:05:10

Yes, exactly, exactly, and maybe one of the best examples of truly addressing exclusionary land use regulations at their source.

Shane Phillips 1:05:19

Well, Emily Hamilton, thank you so much for joining us.

Emily Hamilton 1:05:23

Thank you wonderful talking with you both.

Shane Phillips 1:05:28

You can read more about Emily's research on our website lewis.ucla.edu. Show Notes and a transcript of the interview are there too. The UCLA Lewis Center is on Facebook and Twitter. I'm on Twitter at ShaneDPhillips, and Mike is there at MichaelManville6. Thanks again for listening. We'll see you next time.

About the Guest Speaker(s)