Episode 26: The Future of Housing in California — and the Nation — with Dana Cuff and Carolina Reid

Episode Summary: “We are at a point in Los Angeles and California, where we are seeing the population plateau or even decline for the first time since the 18th century. That is not only a statistical change it is a shift in how we define ourselves and our civic identity.” So says Christopher Hawthorne, one of many housing experts interviewed for a recently report published by the California 100 initiative. What are we going to do about it? In this final episode of season one, Shane is joined by Dana Cuff of UCLA cityLAB and Carolina Reid of UC Berkeley’s Terner Center to talk about their new report (co-authored with the Lewis Center). It outlines the facts that define California’s housing crisis, the history that got us here, and a vision for a more affordable, inclusive, socially and environmentally just future. The report calls for increased homebuilding and a greater emphasis on housing’s role in promoting the public good, not just private gain. Without both, California will fall short of its aspirations, and the rest of the U.S. may follow it down a path to worsening affordability, rising housing instability and homelessness, and declining economic and environmental sustainability.

- Report with Policies and Future Scenarios: Phillips, S., Reid, C., Cuff, D., & Wong, K. (2022). The Future of Housing and Community Development: A California 100 Report on Policies and Future Scenarios. California 100 Initiative.

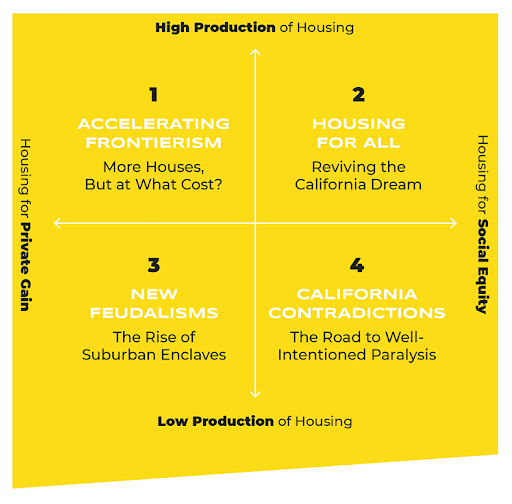

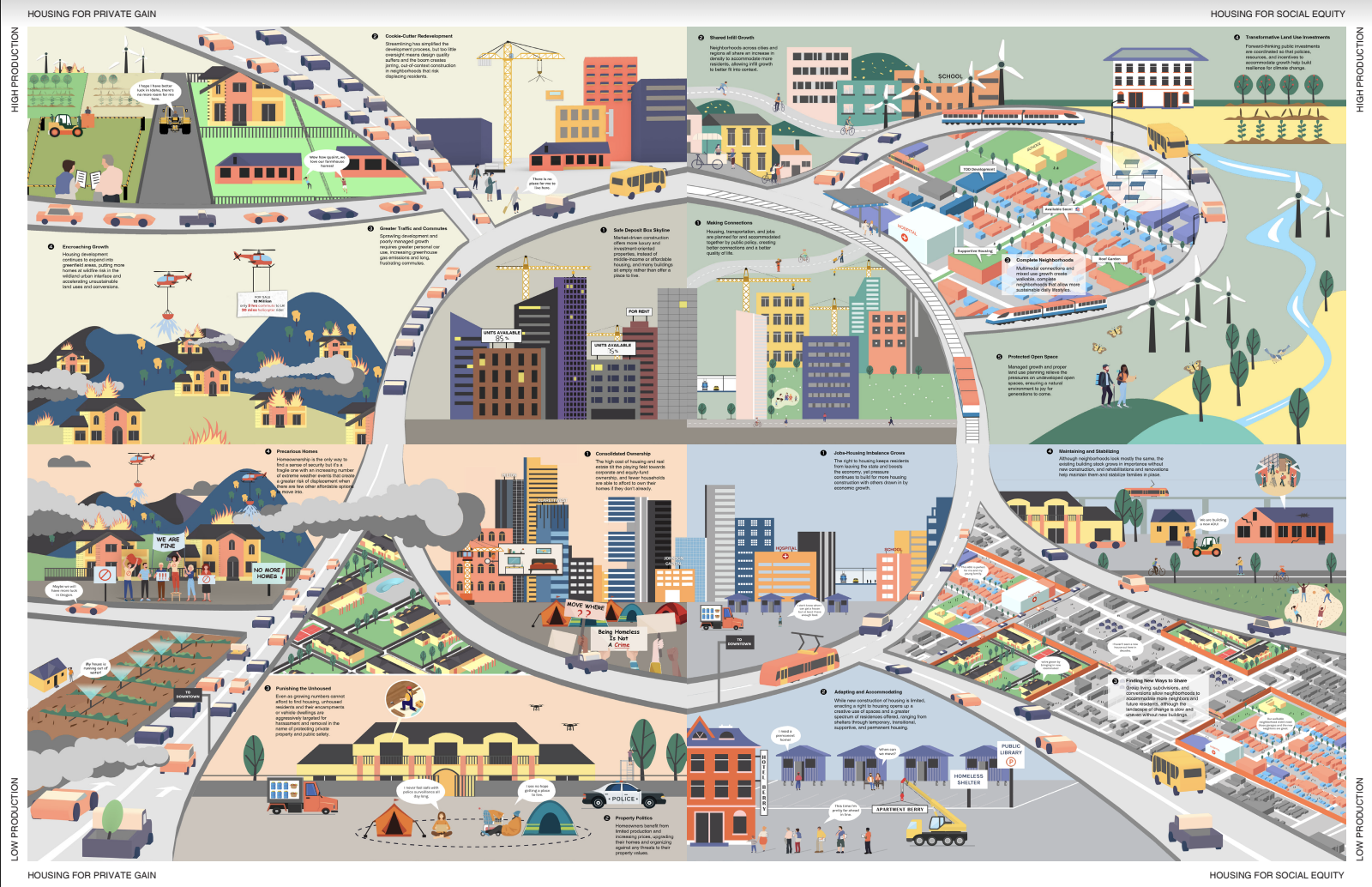

- Report summary: In March 2022, the California 100 Initiative released a policy and future scenarios report on housing and community development, developed jointly by the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Studies, cityLab at UCLA, and the UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation. The teams conducted extensive primary and secondary research, and spoke with a wide array of experts in the public and private sectors to examine possible scenarios and policy options for future-focused action. In their report, the authors outlined the facts that define California’s housing crisis, decisions that led us to this point, and trends that reveal where we’re headed. They describe two critical uncertainties that will decide what the future of housing looks like in California: Will we build enough housing to meet our changing and increasing needs, or will we build too little? And will our housing policies prioritize the role of housing in securing private gains, or its potential to improve social equity? Our answers to these questions will determine whether the future of housing is bleak and inadequate, or bright and abundant, not just in California but across the nation.

- Full report on Facts, Origins, and Trends: Phillips, S., Reid, C., Cuff, D., & Wong, K. (2022). The Future of Housing and Community Development: An In-Depth Analysis of the Facts, Origins and Trends of Housing and Community Development in California. California 100 Initiative.

- Roadmap and Summary of report (four pages).

- Visual representation of the four scenarios, created by cityLAB.

- A Terner Center report on the likely impacts of Senate Bill (SB) 9.

- Baldassare, M., Bonner, D., Dykman, A., & Lopes, L. (2018). Proposition 13: 40 Years Later. Public Policy Institute of California.

- Update: Project Homekey expanded in 2022.

- See more of the Terner Center’s work.

- See more of cityLAB’s work.

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA housing voice podcast. And I'm your host, Shane Phillips. Each episode we discuss a different housing research paper with its author to better understand how we can make our cities more affordable and more equitable places to live. Believe it or not, we have been putting together this podcast for a year now. And this is our final episode of season one. We'll be back in a month or so. But if you've enjoyed the show up to this point, we would really appreciate your support in the form of a five star rating on Apple podcasts or Spotify, or a review on Apple. Sharing the podcast with a friend or colleague is also a big help. This episode is a special one featuring a couple of my collaborators on a report published back in March for the California 100 initiative. My guests are Dana Cuff of UCLA City Lab, and Carolina Reid of Berkeley's Turner Center for Housing innovation. And the report looks at the past, present and future of housing in California. We dig into some of the policies and past decisions that might make California uniquely bad when it comes to housing outcomes, but also the history we share with the rest of US and why our story and our problems are really the story and problems of a nation. The report is a great introduction to the what, why, and how of the housing crisis, and this interview is the intro to that intro. As a part of the report and this conversation, we also envision the future of housing and the critical choices that will shape that future. That also happens to have been one of the most challenging and rewarding parts of the project. So take a listen and check out the report too if you like. The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Louis Center for Regional Policy Studies, and we receive production support from Claudia Bustamante, Olivia Arena, and Hanna Barlow. While we're on break, feel free to send me your feedback or show ideas at Shanephillips@ucla.edu. Let's get to our conversation with Dr. Cuff and Dr. Reid.

Dana Cuff is a Professor of Architecture here at UCLA and the founder and director of City Lab and Architecture and Urban Research Think Tank, and Carolina Reid is an associate professor of City and Regional Planning at Berkeley, as well as the faculty research advisor at the Turner Center for Housing innovation. Dana, welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Dana Cuff 2:38

Thanks for having me.

Shane Phillips 2:39

And Carolina, welcome to you.

Carolina Reid 2:41

Thanks so much, I'm delighted to be here.

Shane Phillips 2:44

So the project we're going to be talking about today isn't quite a research paper like we usually do, it's a report. But I think it's important for a few reasons that I'll get into. And this is also the Lewis Center show, so I can make exceptions when it means we get to share our own work here. To give some background, this report was one of 13 commissioned by the California 100 initiative, each of us tasked with looking at a different aspect of policy within the state. Ours was housing and community development but there were also reports on transportation, advanced technology, immigration, health and health care, energy, and various other topics. We were given two tasks; one was to outline the facts, origins and trends that define the housing landscape in California or to put that another way to explain how things stand today, how we got here, and where we're headed to was to think about what the future of California looks like 20,50,100 years in the future, and what that future might look like, depending on the goals and the values that we prioritize today, and in the coming years. So before I go on to explain more about the project, normally at the start here, we would ask that both of you give us a tour of your hometown or favorite city, but we're kind of short on time. And there's two of you. And so this time, I'd like if we could just each take a minute to share our gratitude to our partners on this project. We were the lead authors along with Kenny Wong who couldn't make it today. But there were many other folks involved with this, and this project really would not have been possible without them. Most of our collaborators were with City Lab or the Turner Center while I was mostly riding solo at the Lewis Center. So I will just start by thanking each of you, Dana Carolina, and also ghost Kenny. I served as the Principal Investigator on the project, but you all carried at least as much weight and made it possible for each of us to play to our strengths. So thank you for your support and your great ideas and for bearing with me with all my last-minute revisions and questions; you're all amazing partners, and I do feel very fortunate that we were able to work on this together. But you also managed a whole bunch of folks who deserve their own plotted, so let me pass it to you, and let's hear it for them as well.

Dana Cuff 5:11

I can start. Yeah, I want to just underline what a pleasure it was working with both of you and the conversations that we had. And also lift up Kenny Wong, who really was the guy who shouldered the majority of the work from, say, labs perspective. He's moved on to be a faculty member at the University of Arizona so he's doing wonderful things, but it's keeping very busy. The other people who were really instrumental on City Lab side were Cassie Haubrich, who did a lot of the interviews, and she's now a consultant in Urban Planning in New York but she did an amazing job, and Chu N Chi, who was the graphic genius behind all of our translations of thoughts about the future of housing into something that we could actually see, and imagine, which I think is really what City Labs' greatest contribution might be. Lastly, Rein Laborde Ruiz kind of did a lot of work for us sewing up all the details at the end and really making our side of it professional.

Carolina Reid 6:19

Yeah, so and I just want to add, it was an absolute pleasure working with the whole team on this. This was a true example of collaboration and the parts being more than the whole. I think that's got that totally wrong but you know what I mean. Shane, thanks for your leadership on this, and Dana, I have to say I'm still totally awed by your team's designs and ability to translate ideas into compelling images. Truly amazing. At the Turner center, I want to do a special shout-out to Shazia Manji, Mickey Kobayashi and Sam Wilkinson for all of their help, data crunching and doing interviews, and then, of course, to my colleagues, Elizabeth Kneebone, David Garcia, and Ben Metcalf, who provided guidance and feedback throughout.

Shane Phillips 7:08

Great, so coming back to the summary of this report and what it was all about. I said, this is important for a few reasons. And one is that I think it serves as a great introduction for anyone just starting to learn about California's housing challenges. It lays out the scale and the scope of the problem, but also traces a lot of history that led us here. So in particular, so much of the history of housing is bound up and explicitly racist and white supremacist policies and goals that over time transformed into superficially race neutral policies. And it's important that we make clear how even dry topics like zoning and tax policy are linked to that really darker past and often perpetuate similar outcomes. Another reason I think this report is valuable is that while it's about California, it can really serve as a cautionary tale and a guide for much of the rest of the country. I talked to folks from all over the US about housing policy, and one of the main messages that I deliver is that California is not really uniquely bad, and housing policy maybe a little bit uniquely bad, but not all that different. We've just felt the impacts of our bad policies in ways that most other regions haven't, largely just because a lot of people want to live here and for good reason. But we're seeing those same growth pressures elsewhere, and a lot of cities and states are just as ill prepared as we were, and are, the good news for them is that they can still take action before things get really bad, whereas we are already in the muck, and it's gonna take a lot a lot bigger lift to pull ourselves out of it. So while the report is very California centric, many of the origins of our crisis and the trends looking ahead, are definitely mirrored across the country. So you don't need to live in California to get something out of it. The last thing I'll say in introducing the report is that it also has a creative component, one that asked us to imagine different futures for California, both hopeful ones and pessimistic ones. And it gave us the space to think about the most critical questions that we as a state need to answer, and how our collective answers to those questions would shape the future of affordability of homeownership, homelessness, sustainability, access to opportunity, racial justice, and a lot of other important stuff. So I'll stop there, but Carolina and Dana, let me pass it to you. Is there anything you want to add by way of introducing the report? I haven't even mentioned all the folks that we interviewed as part of this project. So I definitely want to get into that as we dive further into into the details too.

Carolina Reid 9:54

I think that was a really good summary of both the sort of structure and objectives, and that blending of data and policy analysis, but then also creativity, right? Like the process of imagining, the process of thinking about what alternative futures might look like, we don't get to do that very often, right? We're often in that sort of data and evidence-driven world. And so for me, it was, it was fun to stretch our thinking in that way.

Dana Cuff 10:23

And I guess I would add that, I think, we're not as good at the data piece, though. We do the historical work, and then some kinds of humanistic contemporary analysis. But the future trends is sort of where we focus. But I think, even though, I've been really focused on public impact, and making sure that the research we do has an audience, this report was more guided by its public audience than I think any other I've ever worked on. And I really appreciated the challenge that that presented to us. I mean, we three would get into big academic arguments, and then we'd realize that some of that was really just in our own brain worlds, and what was of interest to Cal 100 was something that was much more translatable. So it forced us to think about those positions and results and data and findings in ways that people could really understand which isn't easy.

Shane Phillips 11:26

Yeah, I've learned this, you know, when you write for the LA Times, or the Atlantic, or someone, it's very nice to have an editor, who is thinking about the audience, which I think as academics, sometimes we don't emphasize quite as much as we should. And frankly, as a part of the reason we created this podcast to try to translate some of the more academic work that is not at all intended for a general audience, when we think it's appropriate. So my plan for this interview is for us to go through this report as it's structured, starting with the facts about housing in California, then moving on to the origins or how we got here, and then the trends that help tell the story of where we're headed, we'll be picking out some of the highlights and major takeaways from those parts of the report, then we'll move on to the future scenarios that we envisioned with the help of our housing expert interviewees, who will talk about later. And finally, the policies that might lead us to the more of those appealing possible scenarios. So let's start with the facts. One thing, and again, we're just going to each kind of pull up some things out here that interested us, it's not going to cover the whole thing. But the one that really stuck with me on the fact is that California wasn't always so wildly expensive compared to the rest of the country. Today, the median home in California is more than twice as expensive as the median home nationwide. But if you go back to the 60s and 70s, the gap was more like 30 to 40% so we were more expensive, but not dramatically so. And that tells me that such high prices are not some natural law of California, they are the result of choices that we've made, or didn't make. And it also tells me that if we in California can go from relatively affordable to wildly unaffordable that other states and metro areas have exactly that same potential to screw things up. Frankly. Another thing that stuck with me was a quote by Christopher Hawthorne, one of our interviewees, formerly of the LA Times, and with the LA Mayor's office the past several years, he said, "we are at a point in Los Angeles and California, where we're seeing the population plateau or even decline for the first time since the 18th century. That is not only a statistical change, it is a shift in how we define ourselves in our civic identity. The fundamental reason people are leaving is the high cost of housing". And obviously, that wasn't news to me or either of you. But I think he put his finger on what a monumental shift it is for us to go from being a growing state to a shrinking or a stagnating state. It's not just about those numbers, as he said, but about how we see ourselves and whether we are a place that continues to see itself as dynamic and welcoming, and always evolving. Or if we are becoming something more static and insular. The answer to that question absolutely shapes our housing policy choices. And I think our housing policy choices have also shaped our answer to that question over the last few decades. So again, to pass this that to both of you. What are a few things about the on the ground facts here in California, that we put in the report that stood out to you or stuck with you in some way?

Dana Cuff 14:49

Well, I think this kind of builds off of Chris Hawthornes comment, but and this has been shaping up for the last 20 years at least. The imaginary in California was always that there was more land and resources beyond wherever you were, that could solve your problem in terms of housing, so you could always move further out. I mean, it was a kind of sprawl mentality. And now what we see even post-pandemic is that all of those areas have housing prices that have gone up; small metro areas have some of the highest housing increases almost double what it was in some of the urban areas. So there's a kind of 'nowhere left to turn' idea that California does have to begin to accept. And I think, with that, the ideas of how to retrofit our cities, so that they actually, you know, bring people the quality of life that they're looking for, but in new ways, without the imaginary of a kind of, I don't know, love it town, or suburban sprawl model. You know, that's where we have to be looking now so that we can get the kind of housing alternatives that we need to see. Because really, there's no further out to go, and that's why I think Hawthornes' comment that people are leaving, at first, we just shifted into different parts of California. Now, people are actually moving all the way out.

Shane Phillips 16:27

And I do think that, you know, Texas is an interesting place to juxtapose against us, because I think, for good reason, to some extent, we point to Texas and say, like, look, it's building a lot of housing and prices are much more stable there. And, and that's all true, and they've actually done some things on infill, with small lot sizes, and things like that. But I think it's also the case that a lot of it is just sprawl. And they're sort of a decade or two behind us. And eventually, they're going to run up against those same limits, not to mention, you know, putting aside the land impacts, and just the sprawling stuff. There's the sustainability and how unsustainable that is, environmentally and so forth, as well.

Dana Cuff 17:09

Well, I think to your point Shane that we shouldn't think of California, as always the leader in this and everyone's going to follow in our footsteps. That's the kind of conceit that I think we could abandon. But when you see places like Arkansas, or Bentonville where they're actually concentrating small metro areas into higher densities, more resources, more mixed use, that's a model we didn't use when we had greenfields that we could have developed

Shane Phillips 17:39

Carolina.

Carolina Reid 17:40

Yeah, I think I think all of these points are so fascinating. And I love the idea that we need to move away from that sort of past imaginary of what California is and where it's going. I think the thing that most struck me as we pulled together all these different data points, and I think it's rare to take such a broad scope on every housing issue within one report. So I think the thing that stood out to me was that how all these factors are really interrelated, right? So that the house and how the rise in house prices and housing cost burdens, is really aligned with rising rates of homelessness across the state, which is also connected to the fact that as a country, we failed to invest enough in housing assistance for low income renters, right. And then if we think about, like, the difficulty of building enough supply to meet demand, especially in infill locations, is also directly tied to the number of structures we're building in the wildlife urban interface, and are now at risk of fire damage, which in turn, are heightening the risk of climate change by increasing commutes and the need for air conditioning right? So I think the full suite of data and charts in the report really brought home to me the interconnected nature of these challenges. And the fact that if we want a more just, and sustainable housing future, we're going to have to tackle the underlying structural causes, not just chip away at the symptoms. Yeah. And I think that sort of also brings us back to Dana's point of, we also have to have a different imaginary of what California is and where we're going.

Shane Phillips 19:13

So let's move on to origins of the housing crisis or just the housing issues we're dealing with. And I think one chart sums up a lot of this for me, and it's the one that shows the gap in homeownership rates between black households and white households over time. And that gap fill between 1960 and 1970, and then it fell again, in 1980. And this is for, correct me if I'm wrong, actually did not think to look at this, this is the whole United States, right?

Carolina Reid 19:42

Yeah but the trends are similar for California.

Shane Phillips 19:45

Right. Right. And so, you know, it fell for a few decades straight. It was still 25 percentage points gap. It was still a very large gap, but it had been falling. We've been making progress. The Fair Housing Act passed in 1968, and it prohibited a lot of the race based housing discrimination that had been permitted up to that point, however, imperfectly. And I think it's reasonable to assume that it played at least some role in the narrowing of the racial homeownership gap. But the gap started to widen again by 1990, and it's increased each decade all the way to the most recent data in 2018. The gap is now larger than it was in 1968, and that's just shameful to my mind, it's really inexcusable. And it highlights a few things for me, one of which is how racism has pervaded the housing market and the policies that structure it for a very long time. And just because we've forbidden, explicitly racist practices doesn't mean the prejudices and even the systems that lead to those practices have gone away entirely. It's no coincidence, I think that a lot of the downzoning that occurred in cities came about around the late 60s and the 70s, right after the Fair Housing Act was passed, or as it was kind of coming to fruition. And the effect was to increase the price of housing. And without ever mentioning race, those cities that down zoned, were able to make it harder for people of color to live there. And that is, of course, a problem that we are still trying to solve and living with the impacts today. Beyond the Fair Housing Act, we also go back to the advent of racial zoning and the invention of single family only zoning in Berkeley of all places, and how that was actually celebrated by the California real estate magazine for its, "protection against invasion of negros and Asiatics". And of course, other things along the same vein, like the exclusion of black households from GI Bill benefits, redlining, racial covenants, and so on. So passing this back again, Carolina and Dana, is there anything you want to highlight from the 'how we got here section'. I feel like this section, in particular, could have been written about just about anywhere in the country, we touch on some very California-specific policies like Proposition 13, and the California Environmental Quality Act. But a lot of the story of our state really is the story of the entire nation when it comes to housing issues.

Carolina Reid 22:16

Yeah, it is a story of a nation. And when we look specifically at racial gaps in homeownership, we are looking at trends in mortgage access and the foreclosure crisis, and then the rise of speculative investors coming in and buying up single-family homes. So I think a lot of these trends are similar across the state. I do want to push back a little bit, because I do think that California specifics like Proposition 13, and CEQA, the California Environmental Quality Act, really exacerbate housing challenges in our state, and make it particularly difficult to address these concerns. And so I think there are structural factors that make us what you said at the beginning of the podcast uniquely bad. And I just want to give a couple examples because I think it's important that we we use this opportunity to imagine different futures to really talk about the structural problems and not just the the manifestations of those. So let's let's just take CEQA, right. It's become what Chris Elmendorf calls a super statute, which holds particular native particular normative and judicial sway and shaped interventions well beyond its original intent. And sequence done a lot of good, right, it's protected the state's natural rich environment, it's provided communities an opportunity to engage in the planning process and have a voice when things are being proposed that impact their neighborhoods. These are all elements of CEQA we want to keep. But the goal of protecting the environment today looks really different than it did in the 1970s. Right now we need to focus on land use, we need to focus on densification. We want to build more housing near jobs if we hope to make a dent in greenhouse gas emissions and CEQA is being misused in ways that prevent that from happening. And I think like prop 13, right also exacerbates the racial inequalities you were talking about earlier, by benefiting older, largely white homeowners and making it more difficult for younger and households of color to buy homes. So I do think California faces some unique headwinds, and we need to develop that political will to be honest about those headwinds and think about how to address them while keeping the good original intent of some of this legislation.

Shane Phillips 24:35

Yeah, yeah, that's a great point.

Dana Cuff 24:36

And maybe, just going back to something Karolina said earlier about the interconnectedness of all these issues, you know, the thing that seems obvious, but we don't often put it together is that while white flight was actually quite pressure to move out right, there was the means by which tax benefits accrued to people who could buy in the suburbs that left the redlined or racial zoning areas in the center without any funding. And so that double effect produced the kind of racialized inequities that we are still absolutely facing today. And you're right, it's a shame, but it also feels like a crime. And maybe we in California have another kind of special condition because as the sort of mother of sprawl, here in Los Angeles, in particular, we allowed that to happen more dramatically than other cities did, which has stronger urban cores, and maybe less land to advantage white homeowners through especially tax benefits.

Shane Phillips 25:55

Yeah, and I do feel like calling it a crime, I mean, I think it's appropriate. And the more that we're seeing households, like younger households, or even older households, rely on family wealth for homeownership, which is just a growing and growing issue where if you don't have that family wealth and generational wealth, often which came from access to homeownership from your parents or their parents, it's a very clear case of sort of the generational impacts, and then almost like a general case of generational theft going on here. And obviously, there's a very heavy racialized element to that as well.

Dana Cuff 26:37

Well, and you know, we'd have to add to this, that all our affordable housing programs are rental programs. And that never is going to assist in the building of generational wealth. I mean, it's one of the continuing inequities that then our solution to people who have been cut out of the housing proposition, their reward is something that's a rental unit, not the homes that in many cases were taken from them through various kinds of eminent domain and other practices.

Shane Phillips 27:13

And we will actually come back to that. I mean, you're you're kind of hinting at the private gain aspect of housing. And that comes up in our future scenarios and our trends. So let's transition here to the trends section. And for this, we considered four sort of macro trends and two things that every report had to include called critical uncertainties. The macro trends that are shaping and will shape housing policies, and outcomes that we selected are climate change, rising wealth, and income inequality, and systemic racism, all of which I think are pretty self explanatory and how they contribute to our housing challenges. And then kind of more creative one, or one we don't hear as much about that we added was political polarization and realignment, which is a different thing. So by that one, we're referring to the certainly the left-right polarization that we're seeing all over the country, and which is starting to creep into housing in some ways, but also the ways in which housing really doesn't fit with the typical political frames. You have wealthy coastal cities that voted 85% for Biden, that at the same time, have some of the most exclusionary NIMBY policies in the state and you know, are 95% White and the median home value is two and a half million dollars. These are not welcoming places when you get down to it. And at the same time, you've seen some Republicans get on board with reforms to promote more housing construction, like San Diego's former mayor who led on efforts to upzone around transit and eliminate parking minimums in some areas. And after that, those reforms took place, the city saw a huge increase in both market rate and below-market housing production. Point being knowing someone's politics doesn't necessarily tell you much about their views on housing. And that's both a risk and an opportunity maybe to create some unusual coalitions. The critical uncertainty section, this is where we are really starting to look ahead, because they shape the four possible scenarios for California's future, which again, I think mirror, at least in many ways, the future of the rest of the country. We're basically asking two questions here with these uncertainties, the way that we have structured them; the first question is, 'Will California build a lot of housing or only a little', and second, 'will our policies prioritize the role of housing in generating private gains, or in advancing social equity?', and I'm sure we'll kind of talk about how those things - can be the intention in some ways. If you can imagine a standard two-axis chart with a scenario in each quadrant, the vertical axis is housing production and the horizontal axis is housing for private gain on the left and housing for social equity on the right. So rather than me continuing to explain all of this Carolina, let me turn it to you. Could you give the audience a little backstory on how we arrived at these two axes, and why we think they're so central to the state's future? I think this was maybe the most challenging part of the project, but also the most fun and rewarding. So I'm sure Dana, and I will also have some thoughts to add here, too.

Carolina Reid 30:32

Yeah, thank you, Shane. And it was the most difficult part of the project, though, I think that challenge was more about figuring out the right framing, rather than any disagreement among all of us about what really matters. I think at one level, we all agree that we need more housing supply, but how that supply gets built, for whom, and where are really important questions that actually sort of determine whether or not that supply is really the answer. A bunch of speculative investments in a luxury condo or sprawling suburban tracts to Dana's point on desert lands, right, far from employment centers isn't what we need in terms of added supply. So this got us to the trickier dimension, what do we really mean by social, racial and environmental justice and housing right? How do we really what do we really mean about what is going to get built and for whom and where. And I think, ultimately, we landed on a principle rather than a specific empirical definition of justice, right a principle that anchors housing as a public good, rather than as a private gain. And just to help make that a little bit more concrete, I think for us, it's a principle that leads to greater investments in housing as a basic need that should be accessible to all rather than what we have right now, which is the inverse, where housing becomes an investment to further wealth building among the few. Right, and so it's thinking about housing as an anchor for community building and community self determination. It's thinking about housing as a place for people to live and raise their families. It's a place for where housing is sort of that that stable foundation on which educational labor market, all sorts of outcomes are better, rather than what we have now, which is, I want to buy a house or I'm going to invest in housing, because I'm going to make a lot of money and be richer, 10 years down the road.

Shane Phillips 32:36

Yeah, yeah, and the social equity, public good aspect of this, I think is it's interesting, too, because it clearly intersects with the production side of things. And I think, you know, in particular, part of what has made housing for private gain so lucrative is because production has been limited. So that scarcity has made homeownership, homes in general, very valuable. And so the link between those two things, I think we all felt it was important to highlight that and also to highlight how these things don't need to be intentional, I do think that's often the frame that we debate these issues along is, is this idea that you're you're either pro-housing, or you're pro-tenant or pro-equity. And that, you know, if you are pro housing, you have to be anti tenant, and if you're pro-tenant, you have to be anti-housing, and just how that can't work in the long run, and you just can't have I mean, I guess you could have social equity with very limited housing, but it wouldn't be very pleasant. It would be egalitarian but we'd all be kind of destitute. And that's like, why would we aspire to that right when we could just build homes and actually combine that with social equity calls? Dana, anything you want to add to all that?

Dana Cuff 34:01

Well, I think I would just say that, in some ways, the myth of this middle-class housing movement after the war, was kind of what you were just describing, Shane, that there was this idea that we could build enough, and we had enough land for everyone. Of course, that was also a veil over white supremacist privilege, but never for everyone, but it did rest on this fundamental idea that you could build something, you could just keep building, and that could work. And I think, in the suburban model, we saw how that didn't work, both in terms of access for everyone, but also in terms of environmental issues. And so in some ways, we've already had a historic test of that model that building your way out of it isn't going to be so sufficient. So in that sense, the question is how do we complicate in ways that can be politically powerful. The idea of building housing that also has a social equity component to it, those together really just haven't existed I think historically, in the United States. We built public housing for the very poor, and that was very controversial. And then we built single-family homes for the middle class. And those two things didn't come together. So that may be is the way we think about this future that has both high production and high social equity.

Shane Phillips 35:42

And, you know, when I talk to folks who are more on the like, pro housing, NIMBY side of things who are more focused on supply, you know, that's how I came to housing, it's still something I feel is really essential. And, and, you know, if that problem is not addressed, then the other things we do are probably not going to matter all that much. But, you know, the more I work on this stuff, the more I just appreciate how, especially for renters, we've just never treated them well. And I think it's largely because they've mostly in the past, been poor people, people of color immigrants, and now as as these problems are creeping up the income ladder and reaching into, you know, other racial and ethnic groups, there's more attention paid to it. But, you know, I think any conception of the future of this country, where we think that things are getting better is one where tenants have a lot more security and predictability about like, what their housing situation will look like, a year, five years from now, whereas right now, that's just not what most places; California is better at this than most places but even then we are, we're not doing enough on that.

Dana Cuff 36:54

Well, I can tell you that, from architecture, you know, we always think about building, that's our job. So building our way out of it has been so much of the DNA of the architecture profession. And I remember a particular conversation that we had the three or four of us with the ghost Kenny involved, where we were talking about the problems of place making, that doesn't include place keeping. And that was a kind of light bulb that went off for me of how I would as an architect, think about place keeping along with placemaking. And I think, you know, there's a way in which that encapsulates some of the issues that we're talking about, about the future of housing in California. How do we keep it so that tenants actually have what you're describing Shane, which is the qualities of life that we've only associated with homeownership before? And how do we make it so that people aren't pushed out of their neighborhoods, when new housing is built, if we have the supply side model, we have to manage also the continuation of existing communities that that just isn't part of the sort of theoretical or practical equations that we've developed around housing and housing subsidy than in the past?

Shane Phillips 38:17

Yeah, and I do want to know, you know, I don't know if we're going to have time to talk a lot about our interviewees. But we talked to folks from all over the state in all kinds of different types of jobs and advocacy and the legal side developers, environmentalists, city officials, state officials, and we heard very consistently, that yes, we need to build a lot more homes. And yes, we need to prioritize social equity in a way that we have not and still are not. And, and really no one saw those things as contradictory, which was really encouraging. I was a little worried that I don't know, just based on my kind of local debates and controversies I see around here. Sometimes it feels like people think it's one or the other. But when we talk to people just all over the place, they didn't feel that way at all. They felt like this is a yes and kind of solution. So let's move on to we kind of talked about trends a little bit. But we gave an overview of the trends on housing production and the ways that we've been trying to advance social equity through housing related policies here in California. And I will say that we've been doing a lot of good things on both fronts in the state in recent years. For me, the defining feature of our progress is intervention by the state government. There's been a realization, I think that we have a collective action problem that every city has individually rational reasons for not wanting to build much housing within its borders. And the overall effect is a state that's buckling under the pressure of frankly, not even very fast growth at all. Certainly not by historical standards, and yet, it's still just feels like it's overwhelming us. We've left things to cities for the better part of a century. And despite their arguments that local governments know best, and that they you know, are closest to their constituencies and communities and know how to plan for their cities. We've seen the outcomes of that approach with skyrocketing housing prices, overcrowding, homelessness, lower and middle income households, leaving the state alongside quite a few businesses as well. And all the other problems we're familiar with. So that wasn't working. And the state is finally stepping up and saying that, you know, someone has to be the adults in the room. And if that means some of you, local governments and officials are going to be angry at us for taking away your toys and so be it. As a result, we've seen things like the adu laws and SB nine that have legalized small scale incremental development all over the state, tons of funding for affordable housing and shelter for the formerly unhoused and tenant protections, like we saw in AV 1482, the anti-rent gouging law that prohibits exorbitant rent increases, and SB 330, which pairs sort of pro homebuilding provisions with really strong displacement protections. I think it's a really great model, combining those two things in one bill, I'll be the first to say that none of these laws or programs go far enough to meet the urgency of the crisis that we're facing. But I also think sometimes it's important to step back and acknowledge how far we've come. And how many of the things that have been achieved in the past five years that we wouldn't have imagined possible, I certainly wouldn't have just, you know, seven or 10 years ago. So thinking about these trends, are there any specific ones that either you want to draw people's attention to maybe, you know, one or two of the bad ones as well, since it's not all rosy here? And we don't want to give the impression that we can just continue business as usual and end up in a better place. Carolina if you will

Dana Cuff 41:58

You go Carolina

Carolina Reid 42:01

Yeah, well, so I agree that there has been considerable progress, and that we should recognize that. I remember going to an event, I think it was like 2014, when then Governor Jerry Brown, literally publicly said that housing was not a priority for the state. And that he was focused on education and climate change. And I had to pick my jaw up off the floor, right? Because housing is fundamental to everything, including education and climate change. I just spent some time looking back at past budgets. And until 2018/2019, the state budget didn't even have sort of a dedicated section to homelessness. And that has changed considerably, right, and so I do think that one of the biggest signs of progress is that housing is on the political agenda. We're passing laws, we're trying things we're talking about it, we're debating about production and equity. And to me, that that's huge progress. And then I also have to say I am encouraged by the unprecedented investments the state is making to address homelessness, there's a long way to go there as well, right? We are not at the solution yet but funding does matter. And for too long, we have underfunded that the equity piece in housing, and so I think moving the needle on that's really important.

Shane Phillips 43:31

Do you have an example or two of those investments that you would want to share?

Carolina Reid 43:35

So I think Home Key is really interesting, again, not totally unflawed as a program, but here is unprecedented investments in acquiring buildings for permanent supportive housing. It's brought way more affordable housing units online, way faster than anything else we've ever done in the past, and at lower cost. Again, it's situated within a fragmented housing financing system so there's still challenges with operations funding and other things. But like, that's, government innovation at work and putting money where your mouth is. And I think that was really good. I think for me, the biggest question and negative is whether or not we can sustain these efforts because the history of housing is filled of examples where we, they tried to do they failed because they tried to do too little or they were abandoned too soon. And so we need to sustain these efforts.

Dana Cuff 44:33

We could add to that propositions H and H. H. H, you know, the funding for permanent supportive housing here which has been strangely misdiagnosed as not being successful. I mean, you know, housing developments take a really long period of time and of course, each unit costs more than any of us wishes it does, but in the long run, those policies are extremely effective and people will tax themselves to pay for them. The problem that I see in that, you know, 10,000 11,000 units that that legislation might provide is nothing compared to the 70,000 people alone we have living on the streets, unsheltered in Los Angeles, and we find 23,000 units per year to get people on the streets, 20,000 I'm sorry, and 23,000 new people fall into homelessness so that there has to be some bigger solution in that. Sorry, Carolina

Carolina Reid 45:35

No, but I think you're absolutely right. And I think it goes back to sort of our key dimensions in that as long as we have rising income inequality, right, as long as we are not investing in renters, right, that inflow into homelessness is always going to exceed what we can build on the other side. And so we need to address some of those, those larger factors.

Dana Cuff 45:58

I want to go back to something you said Shane, about the laws like the ADU law, and particularly SB nine. And I actually see real hope in that. I mean, CityLab was really active in the ADU law, as was the Turner center, I know. And the beauty of that was finding land in the city or in the suburbs that are already built, that was available for housing and could roll out bit by bit. And overall, you know, there's probably, I mean, there's 8 million single-family homes, something like that in the state of California. If a 10th of them built, you know, we'd have a huge amount of new housing and slowly but surely, those new units are getting built. But what I find especially encouraging is that though that seemed radical, when it passed in 2016. Now, we've gone to this new doubling of that idea, instead of just two units per single-family lot, we could now have four units per single-family lot, and that could become two lots. So that, to me, is a radical escalation of densifying the suburbs. And to me, that's a really important trend, that I see great hope in; it's not the only answer. But maybe unlike, say, the housing after 1937, or 1949, when we thought we could provide as a nation, the kind of affordable housing we need. Now we need 30 programs to do that, and one of those might be SB nine, another that we've just been working on is to build affordable housing on school properties. And it looks like that's gonna go forward. So I'm really excited about that another kind of found site model for where housing could be built into communities across the entire state.

Shane Phillips 48:00

Yeah, yeah. And I do think, you know, the, the breadth of the ADU laws, and SB nine is part of the power, just how, how widely spread it is to the point where you have these extra development rights, but you really don't expect land values to go up as a result, because every parcel has that same potential so none of them is special in that way. Whereas the way we tend to do you know, redevelopment and rezoning is more kind of neighborhood by neighborhood parcel by parcel. And a lot of times the land values end up reflecting the additional capacity that we allow on them. And, you know, I think ADUs, in particular are unique, because usually the person already owns the home, and so there is no land cost whatsoever. And I think that the two key things really are no land cost effectively, and then not having to demolish the existing use to build the new one, right, which is a huge barrier. And when you can just add something without taking away, I think that it's a much easier process, smaller hurdle to jump over. Alright, well, let's talk about scenarios here, the scenarios that come out of these two critical uncertainties. As I said, the two axes create four quadrants. So starting in the bottom left and moving clockwise, we have one with low production and housing for private gain, and we go up to high production and prioritizing private gain. Then to the right, we have high production and housing for social equity or public good. And then in the bottom corner, we have low production and prioritizing social equity. Dana, you have to depart us earlier, I'm gonna ask maybe if you could sketch these out for us a little bit and Kenny was really the leader on this. I wish we had him here. Yeah, but you all put together a wonderful graphic with which Karolina mentioned, as well and we'll make sure to include it prominently on the podcast show notes.

Dana Cuff 50:00

Chu and Chi together, yeah, and really Shane when you describe it like that, I feel like I'm taking a spatial relations IQ test or something like, "oh, I can't keep all together". But maybe we could just look at the lower left the low production, high profit, and the upper right, high equity, high production and contrast those two, because that's sort of the crux of the matter. And in that lower quadrant, where we're not building much, and we're going for private gain. So in that lower quadrant, new feudalism, I mean, it's actually not that new. It's actually where we're headed right, and I think you said it earlier, like the lower production actually pushes up the private gain. And so there's a disincentive amongst those who really are working on housing as investment, everything from like older version of exchange values to purely investment, right, people don't even need to live there. You know, companies buying up foreclosed properties, and holding them for highest value. There's a way in which that just pushes all of the worst aspects of what we're seeing today further down that path - greater homelessness, more disinvestment in low-income neighborhoods that need investment. So that contrast, I think, is the frightening future that we could get if we don't start acting on this, in the ways that all of this research suggests so, okay, there's the dark side. When the sun comes up, and our optimism and the optimism of so many people who are in housing come together, it's a California for all picture. And, you know, I don't really think there's anyone who wouldn't want that. There may be greed, that, you know, taints this version but when anyone thinks about the state, we all benefit from everyone having a decent place to live. So that's really thinking of housing as a basic human right, and that we're producing enough housing, as Carolina said, in the right places, for the right people under the right conditions. So that, you know, we have a functioning economy, as well as a functioning environment, as well as the next generation of Californians, you know, growing up in ways that they have all of the access to services and spaces that they need. So both market and non-market, meaning private production of housing, as well as versions of subsidized housing get made in the California for all model. I don't know, I think we've talked about a few of the ways in which that California for all thinking, you can see, glimmers of it, or threads of it that could be braided together.

Shane Phillips 53:07

I did want to pick up on pick up a thread on something you said about how, you know, it's strange that we don't have a California for all right now, and, and our policies definitely don't reflect that right now. Given that you're probably right, that if someone could just wave a magic wand and make it real, almost everyone would support that happening. But in practice, lots of people don't support the things that would make that happen. And it may just be worth thinking about or talking about why that's the case. You know, the first thing that comes to mind for me is just the fact that a lot of people feel like they have a lot to lose. And so they're not confident that the future that we're talking about will come to fruition. So maybe all that happens is, you know, their home value falls and there's no real benefit to anyone. It's just people have less, I don't have a question exactly here. But I think that that's a really difficult and important question of like, 'why is it that's despite it being a pretty universally held, I think what we would like to see the state look like when it comes to the specific policies that most people would agree with, get us there, we just can't, can't move forward, can't come to an agreement on them".

Dana Cuff 54:29

I'm really shocked. I don't know if you two have this same experience, but in progressive conversations, people who are real housing advocates, there's a real intolerance that's brewing around our unhoused neighbors. And I'm really stunned by that. And I think that's partly because it's gotten so broad and, you know, so populated on the streets that people can't see a way out. So one answer to what you're saying, Shane is that I'm not sure people can envision a possible solution, and so instead of imagining California for all, that seems like a fiction that no one's willing to buy into. And then I think is on the other side of, they've got a lot to lose is they can't imagine a way out.

Carolina Reid 55:24

Yeah, I guess I agree with that. I also think that systems work in the way they've been designed. And there are a lot of people and organizations and institutions that benefit from the status quo, and that are making significant wealth off of the current crisis. And so I think we often underestimate the power of those institutions to try and maintain the status quo. And I think that's where we see some of the tensions because the communities that are being most impacted by those speculative investments are now pushing back and saying, "no, right like this, this housing is not benefiting me, it's not benefiting my neighborhood". And so I do think some of the tensions arise around that. And I think it's one of the things that we have to fix most, because even with really positive policies, like SB nine, we're starting to see really different implementation across different cities in terms of what's allowed under SB nine, that's going to sort of undo what you said, Shane, which is that SB nine applies sort of universally everywhere, and so it may not have the same sort of distortion effects. Well, when one city says, well, you're SB nine, has to have all marble counters. Right, then all of a sudden, you're gonna end up with, with exactly that same unevenness. So I think we need to be realistic that it is going to take a significant political shift, and a reorientation to how we think about housing and land and property.

Shane Phillips 57:04

Yeah, I do like that focus on structures. And just in the last couple episodes of this podcast, this has come up - this idea that, you know, our structures are set up to make it very easy to say no, and increasingly easy in some ways, you know. That came up in our conversation with Michael Hankinson, and how district elections increase minority representation, but they also decrease housing supply. And so we need some kind of complementary policies or processes that actually allow us to envision a better future, not just prevent a worst one. And I think that's kind of where we've been stuck. Dana, I know you have to go. I'm going to keep Carolina for a few more minutes, if I can. But thank you so much for joining us today. And thank you for working with us on this project. It was so much fun.

Dana Cuff 57:54

The podcast just reminds me of how much I enjoy these conversations and how much I learned from both of you. So I hope we get to do another project soon, like, take California 100 one more step and actually invent a few policies that reflect some of the findings that we have. I'd love to do that. That sounds great. And maybe one day I'll meet you in person, Carolina,

Carolina Reid 58:15

I know wouldn't that'd be amazing. It's like ghost, ghost Kenny, and virtual Dana.

Dana Cuff 58:24

Alright, thanks so much.

Take Care

Shane Phillips 58:27

So Carolina, with our with our last few minutes here, we just kind of mentioned the policies, which I think you know, we're not an emphasis of this report, I think, in part because the policies we need to adopt are kind of well known and have been so well established in other places. But just to at least touch on this a little bit. If we do want to California where there's enough safe, healthy and dignified housing for all, and where people have real choice about where to live, and have security once they've made that choice. What needs to change - we should cover the headlines in the report here. But I know you're thinking about this question all the time, independent of the work we did on this project. So feel free to toss in anything that we couldn't fit into the report, too.

Carolina Reid 59:16

Yeah, and I think earlier, we touched on a lot of the most important supply-oriented policies. Again, I think one of the reasons the report doesn't delve, too, specifically into any one policy is that for all of those the devils in the details, right, how you structure zoning reform, how you structure tenant protections, those details really matter in terms of making sure that the outcomes are what you want, and that there aren't in unintended consequences. I would say the number one shift or my number one wish of what I would like to see happen is a fundamental reorientation of how we do public subsidies for housing. Because right now, the majority of those public subsidies go to homeowners; homeowners are entitled to the subsidies, right? Like if you are a homeowner and you have a mortgage, you are eligible for the mortgage interest tax deduction, you get it writ large no matter what.

Shane Phillips 1:00:15

Right

Carolina Reid 1:00:15

Whereas for renters, right in California, only one in five renters who is eligible for rental assistance actually gets it. And so I feel like that's what we need to shift and move away from seeing renting as the lesser tenure, and instead as a very viable tenure that a lot of people choose and want to be and invest in the housing stability for renters, as we do homeowners - invest in the asset building for renters as we do homeowners. And I think California could be a leader on this right, we've led the nation on climate change on LGBTQ rights, on early childhood education. So let's lead the nation on housing and put an end to housing insecurity and really, you know, making housing a right for renters as we do for homeowners. So that's what I want.

Shane Phillips 1:01:11

That is a really good place to end, a fairly hopeful California for all kinds of vision. So Carolina Reid, thank you so much for joining the Housing Voice podcast today.

Carolina Reid 1:01:23

This was super fun. Thank you Shane.

Shane Phillips 1:01:28

You can read more about the California 100 report and find our show notes and a transcript of the interview at our website lewis.ucla.edu. The UCLA Lewis Center is on Facebook and Twitter, and I'm on Twitter @ShaneDPhillips. Thank you so much for listening, and we'll see you again for season two.

About the Guest Speaker(s)

Carolina Reid

Carolina Reid is an Associate Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning and the Faculty Research Advisor for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Carolina specializes in housing and community development, with a specific focus on access to credit, housing and mortgage markets, urban poverty, and racial inequality.