Episode 08: Exactions and Value Capture with Minjee Kim

Episode Summary: Many local governments seek to extract public benefits, such as open space and low-income housing units, from new development. These benefits are often negotiated during the project approval process, or they may be tied to local zoning changes that allow for taller or denser development. How best should cities go about this process of “value capture”? Should they do it at all? Dr. Minjee Kim of Florida State University joins us to talk about Seattle and Boston’s very different approaches to value capture and “public benefit exactions,” and what lessons they hold for planners and advocates in other cities.

- Kim, M. (2020). Negotiation or schedule-based? Examining the strengths and weaknesses of the public benefit exaction strategies of Boston and Seattle. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 208-221.

- ABSTRACT: Local governments can secure valuable public benefits from private real estate development through negotiations or schedule-based exaction programs. Nevertheless, few studies have empirically examined their relative strengths and weaknesses. In this study I compare the experiences of two major U.S. cities, Boston (MA)—where exactions are heavily negotiated—and Seattle (WA)—where public benefits are secured through statutory exaction programs with pre-established schedules. I analyze the entitlement processes of large-scale projects approved in 2016 in each city and show that both approaches have their own strengths and weaknesses. Boston was able to extract substantial public benefit packages, but uncertainty was high, and projects were subject to inconsistent decision making at times. By contrast, Seattle’s schedule-based approach was found to be fair and certain while yielding moderate public benefit packages. Despite the commonly held belief that negotiating land uses on a project-by-project basis is associated with significant process delays and a lack of transparency, the case of Boston offers a different perspective. Boston’s projects were approved in a shorter time frame and were subjected to more public meetings per project than Seattle’s.

- Kim, M. (2020). Upzoning and value capture: How US local governments use land use regulation power to create and capture value from real estate developments. Land Use Policy, 95, 104624.

- Manville, M. (2021). Value Capture Reconsidered: What if L.A. was Actually Building Too Little? UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

- Nasar, J. L., & Grannis, P. (1999). Design review reviewed: Administrative versus discretionary methods. Journal of the American Planning Association, 65(4), 424-433.

- Explainer: Residual land value, how it can be changed by rezoning, and the rationale for tying value capture to zoning changes. (See especially the first 3 pages.)

- “Exactions are demands made by local governments to mitigate the anticipated negative impacts of new real estate developments. Localities can impose exactions either according to a nondiscretionary, predetermined schedule or through case-by-case negotiations. Schedule-based exactions include incentive zoning, impact fees, and mandatory affordable housing requirements. Negotiation-based exactions refers to the practice of negotiating public benefit packages during project-specific zoning and entitlement processes.”

- “Despite the many challenges, the flexibility of the negotiated obligations allows local governments to avoid the “average cost problem” associated with imposing citywide exactions; that is, exactions that are “too high” or “too low.” Using case studies of urban regeneration projects in Britain, Spain, and The Netherlands, Muñoz Gielen and Tasan-Kok (2010) argue that local governments are likely to extract better public benefit packages when they are negotiated.”

- Relative strengths and weaknesses of schedule-based and negotiated exactions:

| Negotiated | Schedule-based | |

| Examples | Negotiated public benefit packages associated with development agreements and contract/conditional zoning; planned unit development–associated exactions

Conditions imposed through the granting of special permits and zoning reliefs as well as design reviews |

Linkage fees, impact fees, mandatory affordable housing programs, incentive zoning |

| Strengths | Enhanced flexibility for the developers and the decision makers, which opens up the possibility to arrive at decisions that best further the interests of all parties involved in the process (e.g., innovative design solutions, greater public benefit packages, better control of the pace and intensity of developments as well as strategies to mitigate their impacts, etc.) | Certainty for the developers, decision makers, and the public; fairness and equal treatment for all involved in the process; process is clearer; likely to be less resource intensive |

| Weaknesses | Uncertainty; poor and inconsistent decision making influenced by whim, corruption, and politics; slow; less transparence; legitimacy and distributive equity of the extracted benefits; inefficient use of resources for small-scale projects | Idealistic because it is simply impossible to predict all conditions affecting future land use needs, which can lead to suboptimal development outcomes (e.g., design, public benefit exactions, control of development activities, impact mitigation) |

- “I chose Boston and Seattle to tackle this issue because they are at far ends of the spectrum in terms of the level of discretion cities exercise on real estate development projects. By way of illustration, a 2013 Boston Magazine article deliberately criticized the city for negotiating development deals on a project-by-project basis. Others have also reported that certain developers and neighborhood groups disproportionately benefit from the city’s negotiation-based zoning practice … By contrast, when I conducted preliminary interviews with Seattle’s land use planners, I noticed a stark difference. “We are first and foremost an ‘as-of-right’ zoning city. We try to do that to make it predictable,” remarked one long-range planner. Local developers also confirmed the city’s aspiration toward predictability and certainty. One developer described Seattle as a “straightforward market” with little risk. He saw projects in Seattle as securing development rights “fairly by-right.” The city’s public benefit exaction approach also reflects the principle of the rule of law, which is explained in greater detail in the following section.”

- Boston and Seattle are also very similar markets with respect to population, cap rates, multifamily rent growth and vacancy rates, job markets, etc. Boston added roughly 70% as many multifamily homes as Seattle from 2009-2018, and Boston is roughly 70% denser and has approximately 30% higher rents.

- “The underlying premise of the two cities’ approaches, seeking public benefits in return for additional development capacity, might be analogous, but the IZ approach [in Seattle] is fundamentally different from Boston’s because the zoning code explicitly prescribes the specific size, types, and order of public benefits that need to be offered to secure the additional development capacity. Illustratively, developers in both cities can gain density bonuses in return for preserving historic buildings; however, in Seattle, the amount of additional density that can be obtained is clearly spelled out in the zoning code, whereas in Boston the additional density is negotiated on a project-by-project basis. A developer building in downtown Seattle might choose to provide an urban plaza and gain additional square footage five times the size of the plaza, whereas Boston does not have a predetermined formula for how much density can be gained proportionate to the size of open space amenities.”

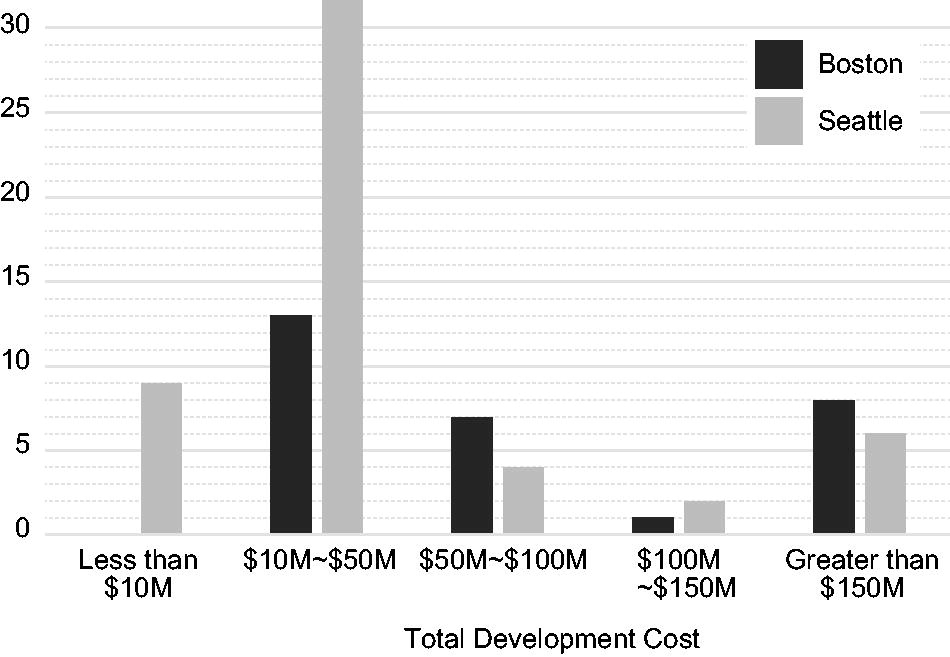

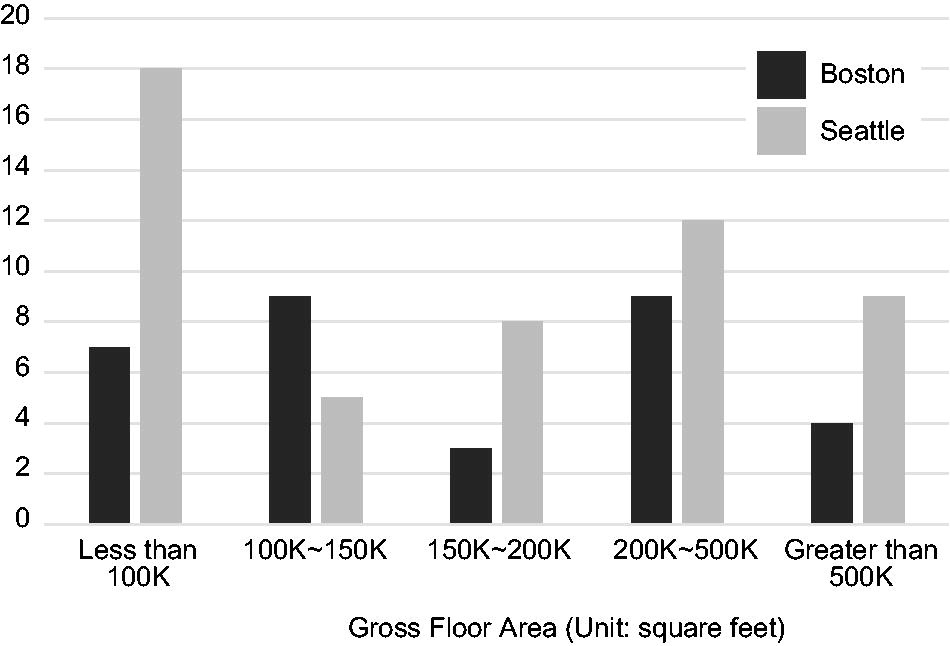

- “As shown in Table 4, Boston approved 32 large-scale projects (more than 50,000 ft2) in 2016 and Seattle approved 52. Most of the approved projects (81% of the projects in Boston and 83% of projects in Seattle) were either residential only or mixed-use developments with a substantial residential component … Boston approved a smaller number of projects, but they were larger in size and higher in value (development cost). As shown in Table 4 and Figures 3 and 4, a disproportionate number of projects in Seattle were concentrated in the 50,000- to 100,000-ft2 range, whereas 80% of Boston’s projects were larger than 100,000 ft2.”

- It’s possible that the uncertain nature of approvals in Boston discourages developers from pursuing smaller and mid-size projects, and lower-value projects. Seattle’s design review process also introduces considerable delay, but it’s probably fair to say that there is still greater certainty of approval in Seattle than in Boston.

- Figure 3, Figure 4:

- “In 2016, Boston secured 431 affordable units in total (302 onsite and 50 offsite affordable rental units and 79 onsite homeownership units) and an additional $15 million. Seattle, on the other hand, secured 32 affordable units and $35.4 million … When all of the monetary contributions were converted to units, Boston extracted approximately 524 units, or about 15.0% of the total approved units, and Seattle extracted approximately 150 units, or about 2.0% of the total approved units … The relatively smaller magnitude of Seattle’s exaction can be explained by two factors. First, Seattle’s exaction approach had limited enforceability and geographic scope. [Second,] the exaction demands were modest in Seattle.” In other words, Seattle required a smaller share of units be income-restricted than Boston.

- “This finding confirms one of the weaknesses of schedule-based exactions, which is that when exaction standards are determined a priori, cities are likely to arrive at standards that are less than optimal. Altshuler and Gómez-Ibáñez (1993) once suggested that the conservative exaction schedules could be stemming from the concern that developers may challenge cities in courts if the exaction schedules are too burdensome. By contrast, considering land use decisions on a project-by-project basis allows local governments to evaluate the economics of individual development projects and ensure that their demands are proportionate to what they are giving to the developers.”

- “Boston, in fact, had only been able to impose such a stringent exaction policy due to its negotiation-based entitlement process. Boston ensures that the IDP does not impair financial feasibilities by having in-house real estate experts—and sometimes external consultants—review and guide each project negotiation. These experts fine-tune the terms of the negotiations (i.e., unit sizes, affordability, and offsite versus onsite) to ensure the provisions of the IDP are met in a way that is financially viable.” This indicates an unusual degree of professionalization in the negotiation of public benefits compared to most cities.

- Seattle also had fewer/smaller open space benefits as part of its projects, as well as fewer other amenities such as childcare facilities and funding to preserve rural land or historic properties.

- “Projects approved in Boston, on average, secure development rights faster than those in Seattle. This is surprising because one of the most prominent criticisms of negotiation-based zoning is its slow process. The median review time for Boston’s projects was 226 days, approximately 7 months, whereas it was 482 days in Seattle, approximately 1 year and 3 months. Seattle’s robust design review process seemed to be the primary reason for its long review period. As discussed above, developers must secure favorable recommendations from the city’s design review boards to move through the entitlement process. However, each design review board meets only twice a month, so projects can get backlogged when the number of projects increases.”

- Although Seattle’s design review board does not allow for negotiation of common public benefits such as affordable units, it seems to introduce similar or even greater levels of delay, but the delays are related to design rather than public benefit elements of the projects. It may be fair to say that Seattle’s design review process is less “professionalized” than Boston’s negotiated approvals process (although the design review commission members are professionals in their fields).

- “On average, 4.2 public meetings were held per project in Boston and 2.4 design review meetings were held in Seattle. The scope of Boston’s public meetings was broader, inviting public attendees to comment and offer recommendations on the project’s impact and potential mitigation measures. In Seattle, design review meetings were strictly confined to design-related issues.”

- “Although, on average, it took less time to secure entitlements in Boston, the variation among the projects illustrates the uncertainty of the process. For example, it took one project (57 Wareham Street) 57 days to secure entitlement, whereas it took more than 5.5 years for another (Garden Garage) due to intense opposition from neighboring residents. By contrast, the longest it took for Seattle’s projects was approximately 3 years and 4 months and the shortest was just more than 8 months, indicating a much smaller variation.”

- “The fact that developers have little control over how long it will take to secure approval renders Boston’s projects riskier. Accordingly, investors and lenders might seek higher returns and interest rates to compensate for the risks associated with entitlement uncertainty. Moreover, investors and lenders might want to work only with developers that have good track records of getting projects approved. Accordingly, developers who are politically less connected, inexperienced, and have little access to capital might be at a disadvantage in a negotiation-heavy regime such as in Boston.”

- “Inconsistent decision making is another issue associated with project-by-project negotiation … [exceptions to standardized exactions] suggests that project-by-project negotiation leaves room for inconsistent treatment, which might lead to favoritism or corruption in worst-case scenarios … Given the lack of standard procedure, huge variation was observed in the scope and magnitude of developer contributions.”

- In Los Angeles this seems especially apparent, where community benefits are often negotiated through an elected councilmember’s office. The requirements can vary widely, giving the appearance of corruption at best and providing opportunities for actual corruption at worst (which we’ve seen).

- “Both negotiation and schedule-based exaction approaches can deliver valuable public benefit packages, but each has its own strengths and weaknesses. The findings from this research suggest that when localities are considering a negotiation-based approach, they must take into account its potential pitfalls and establish guardrails to minimize the misuse of the process. Clear standards, policies, and guidelines must be established to ensure procedural clarity and transparency at each point of the review process. Negotiating zoning for the public benefit, with these safeguards, can become a powerful tool for local governments to secure substantial public amenities from private real estate developments.”

Shane Phillips 0:06

Hello, I'm Shane Phillips with the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, and this is the Housing Voice podcast. The goal of this show is to bring depth and clarity to housing research, and hopefully make it easier to make your neighborhood a more affordable and equitable place to live. Once again, we have a special guest co-host for this episode. And once again, it is someone you may recognize, you'll hear from them in just a moment. So let's get to the interview.

Okay, joining us today is Dr. Minjee. Kim, Assistant Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University, Dr. Kim earned her Bachelor's from Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, and both her Master's degree and PhD in Urban Planning from MIT. Reading your bio on the Florida State website, you say how you worked as a practicing planner while in Massachusetts and found that planners didn't really have the skills or knowledge, at least in many cases, to steward development projects in ways that supported their planning goals. And that in academia, real estate development is often viewed in opposition to progressive planning goals, and learning how it works isn't really emphasized. So despite how central it is to the way most of our cities are shaped, and evolve it, it's just kind of overlooked in many cases. So we have this disconnect that you're trying to bridge with your work, which really resonated with a lot of the work that we're doing here and how I see, you know, my work. This very long introduction is all just to say we were very excited to have you on the Housing Voice podcast today, and thanks for being here.

Minjee Kim 1:44

Well, thank you, Shane, for your wonderful introduction. And also, for having me here. I really want to start out by saying how excited and honored and nervous I am to be on this podcast. This is my first podcast recording. And also , you know, just being here, you know, the past guest lineup has been amazing. And I mean, you know, who hasn't read the work of, you know, Mike and the UCLA trio. So I'm really, you know, honored to be here. And so thank you, Shane, for unearthing my work from the world of you know, arcane academic journals. And you really seem to be doing an excellent job with the podcast, really, you know, drilling into the details of academic research, but also making it approachable to the general public. So I really enjoyed listening to the previous episodes, and we hope that I can, you know, contribute to the conversation.

Shane Phillips 2:38

And we have a special co host again, here today, another familiar face from the Lewis center, and our podcast, Dr. Michael Manville, Associate Professor of Urban Planning here at UCLA and our guest for Episode Three, where we discussed bundled and unbundled parking. Mike Lens is on vacation, and so we figured who better to replace him than another Mike?

Mike Manville 3:00

Yeah, I mean, still you know, my first name comes in handy sometimes. But it's good timing, because I really enjoyed reading Professor Kim's papers, both because I have an interest in value capture, and because I am from the Boston area originally. And so I always like reading about Boston.

Shane Phillips 3:18

Yeah, and it will become clear why that is important. So Dr. Kim is here to discuss her 2020 article published in the Journal of the American Planning Association titled 'Negotiation or Schedule Based: Examining the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Public Benefit Exaction Strategies of Boston and Seattle'. And, this is not a knock on you, Dr. Kim, I'm just there's no way to read these titles in an interesting way. I'm gonna have to like do some post-processing here, and maybe some sound effects or something like that. But this paper is about different strategies local governments use to try to draw out public benefits from new development, especially things like low-income units and open space that's publicly accessible. And these benefit requirements are often referred to as 'value capture' where the government grants the developer the right to build more of whatever they're interested in building, building taller, more dense, things like that. And because those additional development rights have value to the developer, something is asked of them in return. And so I've glossed over a lot of nuance in that summary, and we'll get a lot further into the details momentarily. But first, can you just give us an overview of the two public benefit exaction strategies that you evaluated, which are negotiations and schedule-based exactions? And feel free to correct me if I was misleading in anything up to this point?

Minjee Kim 4:47

Absolutely. Well, I think I do want to start out by somewhat distinguishing the original idea behind exactions versus the more sort of recent framework. So the original idea behind exaction is to mitigate the negative impacts of new developments mostly being transportational, environmental and, you know, strain on existing city services right? So that's the idea that, you know, governments should be asking for mitigation measures to mitigate the negative impacts. However, the idea of public benefit exaction, you know, in present days have evolved to become more of this bargaining framework that you just described. So we'll definitely be coming back to this distinction, and it is not, you know, by all means, easy to distinguish the two different types in any way. But I think it is an important fact to point out to begin with. And then to jump into the overview of the benefit exaction strategies in Boston and Seattle, as I described in the paper, Boston's exaction regime is one that can be characterized as almost exclusively, if not heavily, negotiation based. So almost all large-scale developments have to go through the Boston's Article 80 process, which the name comes from its zoning code, Article 80 of the zoning code that governs the review framework process. And within this Article 80 process, there's this built-in negotiation, you know, opportunity. So for any large-scale project coming into the city to, you know, secure approval, the developers essentially have to submit a letter of intent and then as Citizens Advisory Committee-like entity gets organized in Boston, and then the developers have to you know, present the work to the Citizens Advisory Committee, and then sort of hash out the details before it gets presented to the approval body. And also, the most important aspect of Boston's negotiation basic regime is that Boston historically, ever since the 1980s, has kept by-right density really low. So for developers to build at any profitable sort of scale, they have to come to the city to go through this, you know, Article 80 process. And not all projects are mandated, but to go through the Article 80 process, but if there's any form of zoning relief, or change or amendment that needs to be made for, and in reality almost all projects are like that, they have to go through this Article 80 process, but then they go to a built-in negotiation framework.

Shane Phillips 7:36

And, Mike, I believe you have a phrase for that?

Mike Manville 7:39

Yes, I I tend to call this pretextual zoning, right, which is the idea, as Minjee succinctly put it, you know, you have a law that's its real purpose is to make the developer come to you sort of, and, and offer something because nobody, whatever the height limit is now what, there's 40 feet then or 50 feet before, but the main point is that nobody in Boston's planning office really thinks a development is going to be carried out at some excessively low density, or someone's going to propose a 20-foot tall building, you know, in Copley Square. The law is there, because there's an understanding that the developers will do something to get out of it. So it's a pretext? Yeah.

Shane Phillips 8:20

How about Seattle? How does their planning regime compare?

Minjee Kim 8:24

Right, right. So Seattle came really as a surprise as I started looking into and get to know more of Boston's regime, right? So Seattle, I was trying to see what you know, other cities are doing in terms of their entitlement review process, and then was looking at different major cities, basically, Seattle, Chicago, New York, San Francisco, were some of the major ones that I did look at. And Seattle really stood out as an outlier in terms of how formulaic it was in its public benefit exaction. So I think the basic idea is perhaps the same that you get additional density if you provide public benefit. But in Seattle, that ratio of a benefit versus additional density is always clearly laid out in the zoning code. So for example, in downtown Seattle, for every, you know, square feet of open space that you provide, you get five additional square feet for your, you know, downtown office space. So that really characterized Seattle's approach that it is based on formula, and that it really is all about certainty and clarity in the process of basically what you should give to get what you want.

Shane Phillips 9:41

Yeah, and Mike mentioned, he's from Boston, or the Boston area, I'm actually from Seattle, or the Seattle area, and I lived in Seattle proper for a while before coming to Los Angeles. So we're both familiar with these case study cities. And beyond, I think the fact that their approval processes are so different from one another, the cities in many other respects are very similar in terms of population size, the vacancy rates, the trajectory that their rents had been on, even demographically to some extent. So there's a lot of similarities there as well. So we have these two cities that are very similar in many respects, one of which is very discretionary in its approval process, negotiation based, the other of which is more formulaic, as you said, where if you meet the requirements on paper, then you're pretty much good to go with your project. One thing that we would predict from that is that the less discretionary approval process, like the one in Seattle, would produce more housing. And that is what you find; Seattle approved, I think it was around 20 to 30% more units than Boston, from 2009 to 2018. And a much larger share of those projects were under 100,000 square feet, and valued under $50 million. So in other words, approval processes that are more ministerial, or by right or formulaic, and I'm using those all synonymously, those processes seem maybe friendlier to smaller-scale developers, whereas the more discretionary or negotiation-based approvals are probably a little more favorable to larger developers who know how to manage and maybe have the resources to manage a more uncertain process. They might have more established relationships with elected officials, public staff, their lenders, and so forth. Is that a reasonable characterization of what you found?

Minjee Kim 11:28

Right, right, I think, yes, to an extent, for sure. So I think the key really here is uncertainty. So uncertainty of the approvals process is much higher in Boston, as we'll probably get into the details later in this podcast, but the fact that developers have little control over how long it will take to secure approval, you know, that in and of itself, and whether or not they will secure approval, right? That in and of itself renders the projects riskier, right? And so accordingly, the investors and lenders that, you know, see these investment opportunities, will seek higher returns in return for their investment because it's riskier. Also investors and lenders might want to work only with developers with this, you know, established track record of getting the projects through, right? And so I think one of the outcome of that uncertain process is that developers were, you know, as you've described, less politically connected, experienced and have little, you know, access to capital might be at a disadvantage and likely are at a disadvantage in a negotiation heavy regime, like Boston. On the other hand, though, I do want to emphasize that I don't want to really diminish the history of Boston's development regime, the restrictive, tightly controlled regime existed since the 1980s, as we've discussed earlier, and ever since then, Boston's developers have come to learn, right, that they have to be in good terms with the city to get the projects to go through, right? And they have to, you know, be on good terms with the mayor especially because it's so mayor- centric. And so with that, you know, decades-long history, 50 years of history of being in such an uncertain and negotiation-based regime, I think it's contributing to the fact that it's become, you know, less friendly to smaller-scale developers, but part of the goal of the paper is also to sort of add nuance to this, you know, perception that negotiation based regime does not always have to be like that, and which is what Boston is, in fact, doing to improve their negotiation base regime in. And also, you know, in Boston, yes, in Boston, you see less diversity in terms of architects, consultants, and developers who are in the, in the business of building. So I think it's a factor of, you know, multiple forces that are at play.

Mike Manville 13:57

I think, you know, I just want to highlight what you just said, because I think it's a really important point that sometimes gets overlooked when we talk about development, which is that once you have a system like, like Boston's, which does involve a lot of back and forth and uncertainty, and in many respects, where we are in Los Angeles, parts of it looked like that here, too. I mean, one of the results you get is, as you put it, that a developer has to be more than someone who can deliver a physical structure, and they have to be someone who can, who can deliver a permission through the system. And that really does select for a very different kind of person, like you can't just have someone or an institution that was good at building housing anymore. You have to have someone who knows how, as you put it, to stay on good terms with the mayor. And I think, you know, what's happened as a result of that, is that in this effort to get, you know, some concessions from developers, whether they're exactions, or value capture, in exchange for housing, we've also created an impression that a lot of people find distasteful, which is that the developers are just very closely tied in with the government. And it has this whiff of cronyism. And sometimes, of course, it really turns into corruption, that happened out here in LA this past year. And so I think they are, and I would be interested in your thoughts on this, because when you said it's sort of triggered this thought process in my mind, I mean, they really are sort of really tied up in each other. If we have a system where we want the developers to really be on good terms with the powerful people, we're also courting a suspicion among the average person that like, "Oh, these guys are just cronies, and they're kind of tied up with each other".

Minjee Kim 15:41

Right, right. No, there's absolutely no, you know, denying the fact that negotiation-based discretionary regime leaves room for potential misuse. And, you know, at worst case scenario, abuse of that discretionary power right? And, I mean I suppose that that's true with any discretionary power that's given to a decision-making body.

Mike Manville 16:02

I agree

Minjee Kim 16:03

Right, and so the public trust and the planning process, and the development control clearly takes a hit because of the perception, whether or not the corruption is real or perceived, right? And as you you know, seem to hint at, both you and Shane, there's a lot less actual corruption that goes on behind the doors than what it is, especially in my opinion today's world where everything from personal emails to social media accounts are all under public scrutiny, it's, you know, a lot more difficult for that type of corruption, the one that we're thinking to happen, but in terms of the, you know, public trust and the perception, you know, there's no way of denying that. And the yearning for, you know, certainty, uniformity. I mean, that's what gave rise to the zoning in its first place, so that that will not go away, especially given the best-vested interest of the property owners, people want to see, you know, what's what my neighborhood is going to look like, in the future? Right. So I think that's, you know, the negotiation-based regime clearly, you know, starts off at a disadvantage point when it comes to public trust in the planning and development process. I do think that the more you bring the negotiation part to the public, and to use that process as a forum for hashing out the details of the negotiation, I'm thinking more along the lines of community benefit negotiations that can happen in a way that is not seen as, you know, backroom wheeling and dealing, right, I think the more light the negotiation process gets the less actual and perceived corruption issue that you will have. And which is what, in my view, Boston is really trying to do is to put that negotiation to the forefront of the, you know, of the public review arena.

Shane Phillips 17:59

Yeah, here in Los Angeles, and I think this is true of many places, it's essentially up to the council member to negotiate these things, and usually the other council members who represent different districts where the development is not occurring, they just kind of go along with whatever the one who actually represents that area agrees to. And as you say, that's, you know, we've had two FBI investigated, one's already been sent to prison or jail or whatever, in the last year, and another is probably headed there soon, out of 15 council members. So these things can get to that level and having it so controlled within especially just a single office where it's really just a single elected official can result in that. So I want to move on to what we talked about so far, the total production of buildings and the kind of skew toward larger buildings in the more discretionary process, that's sort of what we would expect, based on you know, most theories about how this stuff works. The other prediction would be that negotiations would yield more public benefits, but probably slower approvals, whereas the schedule-based exactions would produce fewer benefits, but faster approvals. And that's not actually exactly what you found. And so can you just tell us what the results were in terms of public benefits like affordable units and open space for Boston and Seattle, and how long it took to receive the approvals in each case.

Minjee Kim 19:24

Right to state it in one sentence, right, in the interest of time, Boston did extract much greater extent and magnitude and types breadth of public benefits, than Seattle. Just illustratively in Boston, 431 affordable units and $15 million were extracted just in 2016, large-scale projects. Seattle on the other hand, 32 affordable units and then 35.4 million. I've converted the dollar figure into units and it comes down to Boston extracting 15 percent of the total market units as affordable versus Seattle being, you know, 2.2%. So that's a huge difference. And then I'm also in Boston, more than 1/3 of the projects have pledged to provide substantial open space for the surrounding community for the city. In Seattle, about 1/5 of the project did so but in terms, when you look at the details of what these open spaces will look like, it's clear that Boston's open spaces are going to be much more significant, you know, actual park spaces, playground, dog park versus Seattle's would be more through block, you know, connections and, you know, publicly accessible courtyards, etc. And then Boston also extracted additional miscellaneous public amenities, which sometimes are direct monetary contributions to community organizations and nonprofits. But also other times, you know, contribution to existing open spaces contribution to you know, transportation improvements, versus Seattle, that, you know, additional benefit was also really small. So I think, overall, it is fair to characterize that Boston extracted much greater, you know, magnitude and breadth of benefits than Seattle, based on the 2016 data. In terms of the review time, as you suggested, it was it was surprising that the median time for Boston was much shorter than Seattle. In Boston, it was seven months, with the median review time; in Seattle, it was one year and three months. And we'll get into you know why this is the case in Seattle. But what's important to point out is that in Boston, the variation is pretty huge, right? If a project sailed through the review process, one project in 2016, was approved under 60 days, versus another project that was also approved in 2016, to 5.5 years to get through the line.

Shane Phillips 21:55

Which goes to your point about uncertainty.

Minjee Kim 21:58

Uncertainty right exactly exactly. And then in Seattle, the projects on average, you know, the longest it took was three years and four months still really long but you know, it's less than Boston, and then the shortest was still more than eight months. So that variation, there's a huge difference.

Shane Phillips 22:18

Let's dig into both aspects of that, the public benefits and approval speed just a little further. In the paper, you mentioned something called the 'average cost problem', which was something I'm not sure I'd heard the actual phrase before, because I am not well-read. But I was familiar with the concept generally. And how this average cost problem is perceived as a shortcoming, it's a shortcoming to schedule-based exemptions compared to negotiated exemptions. Can you just explain that term and give us a little background on why negotiations are expected to yield more public benefits for a given project?

Minjee Kim 22:53

Absolutely. And, you know, I do not blame you for not knowing the term because this was the first time that I've come across, you know, someone actually coining that concept too as I was writing the paper. So the idea of average cost problem is that, it's simply that it's difficult to, you know, arrive at a perfect average cost when the circumstances are so uncertain. So let me just explain that through example. So real estate development ventures are, you know, by nature, inherently highly sensitive to market conditions, as we all know. And the market conditions are highly volatile, right, so you can have a strong market today, and then there's a great recession, so then it tanks so because of that, you know, highly volatile market conditions, when rules are set up upfront, cities cannot confidently predict what tomorrow's gonna look like, and then set up a standard that is, you know, commensurate to the market conditions of the future. So because of that future uncertainty, cities are essentially forced to put in place, basically arrive at an exaction standard that is, you know, much lower than what it can be under, you know, the optimal conditions, which is more and more sort of conforming to the negotiation based regime that you're negotiating the project's economics, you know, almost real time. So that you can take into consideration strong market conditions and can ask for, you know, high greater extent of public benefit under that stronger market conditions. And so if cities, on the other hand, are creating rules based on current strong market conditions, there are inevitably again, going to run into opposition from the development industry, from the landowner saying that, "oh, you're looking... you know, you're using the assumption that are too rosy" because, you know, today it might look good, but tomorrow, it might not. And so it's generally you know, as a political backdrop, I think it's generally really hard to establish schedules that are highly demanding and which kind of is, you know, a long-winded way of explaining the average cost problem. And also, I think the other main piece is that cities are, and local governments is what I mean by cities, that they are generally highly, highly risk averse in terms of lawsuits. So when planners and planning departments begins to engage in, you know, exaction schedules, they are essentially going to be told by advised by the city's attorney's office to, you know, sort of downward project the future conditions and thus see, you know, how much they can extract.

Shane Phillips 25:36

Right, and even if they were to be too aggressive, and that wasn't a concern, or they had a good justification for, we're going to set, you know, these exactions at a pretty high level, if they did so in a way where it made, you know, a lot of developments in feasible, that might be the case the day it's passed, but five years from now, maybe the market changes, it actually gets more favorable. And, you know, you can get higher rents and these kinds of things. And so over time, something that might have been too high, or maybe even set just right, it might not be in the future, where, you know, rather than asking too much, you might be asking too little as well. And so either way, it's very unlikely that you're going to be right in that sweet spot for very long at any given property.

Minjee Kim 26:21

Exactly. And given that it's difficult to change the rule of the game right.

Shane Phillips 26:24

Yeah, yeah.

Mike Manville 26:25

Right, and I think there's an endogeneity in there, too, that's worth thinking about. I mean, just take Shane's point a little bit further, which is that if you set things too high and deter some development, then in 10 years, all else equal, you have the right demand, because your housing prices will have high enough, in part because of your rules, that they become feasible. And certainly, you know, Boston in the 1980s, was just a very different housing market than Boston today in the sense that it was just starting to turn around from a period of terrible decline. I mean, if you look back at Boston in the 1980s, and look at the rhetoric of Ray Flynn, and some of his advisors about like, what are we going to do about all this development? I mean, it's very funny to think about that today because it's like, "what development?" You know, I mean, obviously, there were some cranes there but Boston had been emptying out, you know, people were talking about, it was finished as a city. Whereas, you know, when I was growing up, like, yeah, the area near Park Street was called the combat zone. And now you can buy like a $10 coffee there. And so it's a... but this goes to your point about how hard it is to change a regime once it's there, but that the initial conditions are often very different from what we initially anticipated.

Shane Phillips 27:41

And I wanted to build on this a little further, I guess, the point I want to make is that maybe the average cost problem is not such a problem. So as an example, we have here in LA, something called the 'affordable housing linkage fee', which is a fee, we tack on to certain developments to help fund low- income housing projects or units. But the fee has actually been set higher in wealthier parts of the city like West LA than in other parts of the city. And it's, you know, maybe not stated explicitly, but it's because of this average cost problem. There's this recognition that, you know, the market is stronger in West LA, and we're probably asking too little if we asked the same in East or South LA as we do in West LA. But as I said, I do think there's some benefit to this. Because if we have an equal linkage fee across the city, that's going to tend to give projects in those wealthier areas, a little bit of an advantage over developments in poorer areas in terms of feasibility. And, you know, I think Mike and I agree, and I think it's kind of the common belief among professional planners and academics and so forth, that we actually want more housing to be built in higher income areas rather than lower-income areas, in places where there's more access to good jobs in schools and parks and other amenities, and less risk of displacement of more vulnerable households. So, you know, I feel like this comes down in part to whether you want to put more stock or prioritize maximizing these really explicit public benefits. Or if you're more concerned with these kind of more intangible benefits of increasing access to higher opportunities and providing more housing in those locations. What are your thoughts on that trade off?

Minjee Kim 29:23

So I think, I mean, what you're talking about essentially is boiling down to whether exactions like, what impact do exaction policies have on housing production and affordability right?

Shane Phillips 29:35

And the locations of where the housing gets built, which I think is a really important question. And a debate that's going on right now is not just how do we build as much housing as we can, but how do we make sure it's being built in the right places where we can provide the most benefits and do the least harm, you know, in terms of displacement and things like that?

Minjee Kim 29:52

Right, right, absolutely. And I do want to point out that, in my view, the dynamic will be different, is different if we're talking about building, you know, duplexes or townhouses in a predominantly single-family neighborhood, versus we know if it's in a wealthy neighborhood, for example, versus developers of multifamily commercial real estate projects. And I say so because project feasibility for multifamily commercial developers aren't probably impacted too much by the higher exaction standards. These developers will essentially say that as long as the rules are stated clearly upfront, and they can expect how much they need to factor in, in their, you know, proforma, this is okay because they're essentially going to pay less for developable sites.

Shane Phillips 30:41

Right, that's the residual land value.

Minjee Kim 30:44

Exactly, exactly, versus economics for small-scale home and condo builders are completely or largely different. The cost of impact fees and linkages almost, you know, instantly gets passed on to the final home values or prices. And that's because these smaller scale builders and developers don't back out the purchase price of land, from how much money that can be made minus the construction cost, the residual land value idea, they don't do that. Generally speaking, they instead determine how much to sell the house for depending on the cost of the construction and the land value. So for these developers, if impact fees gets, you know, tacked on or linkage fees, or whatever, the final home values are going to increase and versus that translation or transition is as as direct for commercial multifamily apartment builders. So I don't necessarily think that it's a one to one trade-off when I'm thinking about exaction policies versus housing production, and that there's, you know, a lot more nuance that gets missing when we're talking about how exaction policies and affordable housing policies, linkage fees impact the actual production piece of that.

Shane Phillips 32:07

Yeah, I do want to hold on Boston and Seattle for a little bit longer before we go too far into the more philosophical conversation, which I know I let us do so I'm not faulting anyone else here. But we were talking about the timing, and this kind of surprising result that the negotiated process in Boston is actually faster on average, or the median time is faster, it's actually less than half the amount of time than the schedule-based process in Seattle. And it seems like Seattle's design review process is really the culprit here. Seattle has its own discretionary process, it's just not for the exactions. So can you give us a little bit of that background, and just this interesting result that came about here?

Minjee Kim 32:54

Absolutely, absolutely. So Seattle has a highly discretionary design review process, as you alluded to, and that definitely has been the bottleneck for its entitlement process. And in some city essentially, has eight standing design review boards that are made up of volunteering citizens, which are representative for different professional backgrounds, like architects, landscape architects, you know, builders, etc. And so each Design Review Board has five members, and these boards meet twice a month, which is quite taxing for a volunteering, you know, group of citizens, right? But because they only meet twice a month, there's only so much that they can review per per month. And the entitlement process, the discretionary design review process, is a two-step process so there's this early design guidance meeting that reviews the overall massing and general sort of scale of the building and how the building is gonna, you know, the volume is gonna look like, and this early design guide process alone could take multiple rounds. So if you think about, you know, meeting twice a month, and then going through multiple rounds of early design guidance, and then another round of detailed design review that, you know, talks about materials, you know, front access and, you know, sidewalk sort of appearance, and that could also take multiple rounds, technically. So then if you add up that process, it's a lot to be adding to the being entitlement timeline.

Shane Phillips 34:29

And I do want to add that the process is it's changing the design, potentially, but I guess there's a question of 'is that the thing that people care most about?' We're spending all of this time on, you know, making these tweaks to the design, maybe they're big, maybe they're small. But as you say, in your paper, the design review commissioners are not allowed to say, "we think there should be more affordable units here", "we think you should change the number of units", those kinds of things. I don't even know if they can really require more open space or that kind of stuff. So it's a lot of time spent on, I mean, I don't want to imply that the design doesn't matter, but I'm not sure it's what most people would consider, like the highest priority and for it to be this thing that is maybe adding six or 12 months to a project's timeline, it seems like a poor use of resources maybe.

Minjee Kim 35:24

Right. I mean, I think that's a really valid critique. And you're right, that the content of the design review meetings are strictly design, you know, focused that you're not supposed to negotiate in any aspect, the overall density or the height, or, you know, public benefit, for that matter. It's about the design details and, you know, the massing. And so I think your critique is really valid in the sense that Seattle is spending, you know, a whole amount of time on these design review. I do want to point out that the developers that I've spoken to, in Seattle, don't really have too much complaints about the design review process, because they know that although it's going to take long, that they know that, you know, it's not a matter of, "will I get approval or not", it's just right, will my building look like A or will my building look like B so I can add in that, you know, several extra months, as long as I can predict what the final outcome is going to look like. So although it's, you know, it's adding to the entitlement process, I don't think it's, you know, necessarily being viewed as you know, detrimental to Seattle's entitlement process in general.

Shane Phillips 36:40

It doesn't have that like 'project killer' potential, at least.

Minjee Kim 36:43

Right right, so you're essentially, you know, as we discussed, fine-tuning the design details, not the print; we're not debating the merit of the project itself. So and, you know, I do think that the buildings, the final outcomes do look really nice in the design sense that they are very context sensitive. And in terms of massing its detail. So I do think very highly of the process itself but it is true that it's a lot of time spent on design.

Shane Phillips 37:17

I will give Seattle credit, having been from there and going back occasionally, buildings tend to look a lot nicer than what we're building here in LA, unfortunately.

Minjee Kim 37:26

Or in Boston.

Mike Manville 37:27

I mean, although what's funny is that LA does, in some neighborhoods, have design review. And so it is an interesting kind of efficiency question. I mean, I think in some places design review becomes, unlike in Seattle, a backdoor way to try and take some units off and things like that. And it's good that Seattle doesn't do that. But it would be an interesting, almost purely academic question, to try and determine if in these places, it really does get you better design. You know, it seems like in Seattle, it really works. But you know, you could just imagine talking to people and say, like, "what if we designed the building by committee at the very end of the project?", and, you know, see people sort of shudder a little bit, especially for something that really is, you know, not just to Shane's point, maybe not the most important aspect of the building, but also, you know, truly in the eye of the beholder.

Shane Phillips 38:15

And architects have very strange ideas of like, what makes a beautiful building. I feel like if architects universally love something, it's a very good chance that regular people are not going to be big fans, cause it's gonna be very high concept... we don't have to go too far down that road. I will say, a good paper I read a while back with a great title is called 'Design Review Reviewed'. And in that paper, this is from I think a few decades ago, but they did find that people who were surveyed about buildings that went through design review, did not find them to be more attractive or pleasing or whatever. But I will say that the scope was pretty limited; these were more like single-family homes and kind of relatively minor revisions, as opposed to, you know, the design of an entire seven-storey or 40-storey building, which I think there probably is more of a role for some kind of, you know, I don't know how you do an objective design review.

Mike Manville 39:18

But you probably can't, and this is the last I'll say about it, because I know we want to move on. But there is a role for something like it, I think if only because, as planning became more technocratic, one thing that did get lost, I think was an emphasis on how the city ultimately worked. You know, that when planning was purely 'did you hit this numerical benchmark and that numerical benchmark', you know, oftentimes what got spit out was just, almost everybody agreed it was unattractive. But unfortunately, I think a lot of the parameters that determine that aren't things that are subject to design review. I mean, I have my particular bugaboo, which is parking requirements, which I think, you know, dramatically changed the aesthetics of almost any project. And have made Los Angeles, huge swaths of it, very ugly. But unfortunately, a design review committee can't say "you don't have parking requirements". And so, in some respects, the people charged with design review are also working with such tight parameters, that their real ability sometimes to make a building better looking is limited.

Shane Phillips 40:19

Another thing that stood out to me in this paper is just how really unusually well run Boston's negotiated approval process seems to be compared to my understanding of negotiated and discretionary processes generally. The city has in-house real estate experts, and they sometimes even bring in external consultants to work on the negotiations. And based on the approval timelines, it seems like they bring them in pretty early and don't really let that hold things up too much. And that strikes me as a pretty unusual practice, in most places, it just seems like the demands made are not really based on evidence. It's kind of just both parties, the city and the developer or the community and the developer, trying to get as much as they can, you know, and try to win the negotiation. Basically, I think, you know, Mike and I are certainly advocates for by right approval processes, generally. But your paper makes it clear that you can have that ethos of, you know, we're going to make things very straightforward and by right, but the details really still matter, as the discretionary review process shows, and it just takes one dysfunctional link in that chain and things kind of fall apart to some extent.

Minjee Kim 41:32

Yeah, no, I can't agree more with, you know, how you've characterized it, that the details really matter in these processes. And yes, absolutely, I agree with you that Boston by far has one of the most well-managed development review process that is negotiation-based. But this has to be understood in context that I really didn't have enough space to discuss the historical and political background of how Boston came to have such a, you know, well-functioning system. And in most people in Boston, in fact, and Mike might agree with this, would be really surprised to hear that Boston has a functioning negotiation based review system.

Shane Phillips 42:15

It is all relative

Minjee Kim 42:17

Right, it is all relative. But historically speaking, the public rarely had a clear idea of how projects were reviewed and approved by the city up until really recently. This really changed when Mayor Marty Walsh, who took office in 2014, became the mayor, and who recently stepped down earlier this year to serve as the Secretary of Labor. So Mayor Walsh made it a priority to make the design review process transparent and accountable. And so as I was in working with the Boston Planning and Development Agency, that the Agency was really trying to reinvent itself as an entity that, you know, is mainly based on negotiation-based regime, but trying to make it as transparent and accountable and, you know, to the extent that it can be made. So this experience from Boston, I think, suggests that you can certainly have a negotiation-based regime that is highly secretive, you know, backroom wheeling and dealing or you can also have a pretty well-functioning and professionally managed system. So it really all depends on how the process is designed, managed, and implemented. And again, going back to the point about devil is really in the details with these development reviews. And Seattle, on the other hand, I mean, I wouldn't call it dysfunctional per se, but it does dispel the myth that, you know, schedule-based regime is inherently going to be faster than a negotiation-based one. So I think, it's sort of, you know, shows the best and worst worlds of, you know, both types.

Shane Phillips 43:55

Yeah, and I'm not sure that these cities are the best example of this. But, you know, I'm thinking about how a lot of the outcomes we see, they're not really a product of specific policies and processes, at least not at at the root. It's really, how does the city and its leadership feel about development, and the policies will kind of flow from that. And so if you have a city that's just not very friendly toward development, maybe they've got by right approvals, but they're going to find other ways to put up barriers. And likewise, if you're pretty friendly toward development, you think like we need to build more housing or office space or whatever, and you have a negotiated exaction process, you can still find ways to make that work, if that's in your interest to do so. And I'm not saying anything new, this is something that.... Mike I don't know if this is actually your work, or if it's Paavo and Mike Lens or if all of you guys, but this is something you guys have talked about quite a bit.

Mike Manville 44:55

Yes, we have. I don't know which one of us came up with it... we all say it. We've merged into a single. I mean, I would just say, log honesty, because it was one of the most striking things about the paper to me as well was the extent to which Boston had really kind of professionalized this negotiation. And I hope you can't hear it, but my dog is chiming in as well, I think she was also a fan. But I think it really reinforces a point that is lost too often in planning discussions, especially when.... oh, gosh, I'll feed you later, especially when we talk about things like development negotiations, which is just this simple point, which is just, you know, good government is kind of expensive. You know, you can argue about whether you want to have a discretionary regime or not, but if you do, you know, you should invest the money, the taxpayers should be willing to invest some money to make sure it's really good that you have professionals and so forth. And so the contrast that struck me when I read that part of the paper was with Los Angeles, where discretion is really seen as a way to push the costs of a lot of public services onto developers, and where it's, you know, relative to Boston very understaffed, you know, it is just kind of like it, city council members kind of deciding what they want. And I think, you know, you could have, you know, again reasonable people can disagree about how much discretion we want to have in the development approval process. But whatever that amount is just this thing that we've lost in this era of austerity is this idea that, "well, you know, you should pay people to be good professional civil servants who do a really good job at it, and you'll get better outcomes". And I think there's a political atmosphere in too many of our cities that we want to do it on the cheap. And then, you know, still, we're disappointed when it doesn't come out the way we want.

Minjee Kim 46:50

Right, no, I agree with you. And it sounds to me, like, L seems a lot similar to how Chicago functions in practice, as well. That's Chicago's alderman ultimately has the, you know, almost exclusive control over what gets built within their jurisdiction. And that city staff are rarely involved in the negotiation process, that it all gets baked before it even gets to the city. And I do have a different paper that talks about the different styles of entitlement processes, including Chicago, New York, I didn't look into LA, which is why I don't really know much about LA, but it does go.... part of it can be explained by the history of the city's development regime, and also how the zoning has evolved over time in each city. So I think it's historical, you know, there's a historical component to that as well.

Mike Manville 47:55

Absolutely, yeah, I think many processes in our cities would not look the way they do if someone designed them all at once. Right, they kind of emerge and we work with them as they emerge.

Shane Phillips 48:07

Yeah, this is an aside, but I've been following here in Los Angeles, this proposal to expand something called 'fire district one', which prohibits certain types of construction mainly in downtown LA. Basically, certain types of wood construction that are feared to, you know, be more likely to burn down. And the city just created a report, in response to a council member's motion to evaluate expanding this program. And it was really interesting, like at the beginning of the report, how they just said, "we don't actually know where this came from". And so for that reason, like we're talking about expanding this program, that we don't really know why it exists in the first place, or what motivated its creation, I feel like that kind of status quo, it was a really good example of that inertia to me. So before we close out, I do want to get into the more philosophical conversation about value capture a little bit here. And Mike published a really great paper just a week or two ago called 'Value Capture, Reconsidered', which we'll include in the show notes, and is on the Lewis Center website, but him and I even disagree on some of this, just at a philosophical level. And so I want to kind of get both of your views on this. But the way I've been thinking about this concept of value capture is if you took a city the size of LA, where most properties are zoned for only one home, and all at once you just change the zoning, so that you can now build 10 units on every single parcel, that would be a massive increase in the total capacity of the city. And because you've rezone everything, the price of land might not actually go up, because there were just so many potential sites for developers that you know, they would be maybe willing to pay more but because the property owners wouldn't have the market power to demand more, they could build these 10 unit buildings with much lower land costs per unit because the land costs hadn't gone up to acquire it. And you know, because of that, we'd get a lot more homes built. And those homes would be more affordable, because, you know, the land would make up a smaller share of the total cost. In that case, because developers had the market power, it's the buyers and renters of this new housing, who would benefit from lower prices. If you instituted some form of value capture in that situation, you'd really be, you know, you might have one or two units out of the 10-unit building that has to go to a low-income household. But the other eight or nine units would have to be a little more expensive in order to cover that cost. And so you'd get a little less housing overall, maybe a lot less housing overall, just because there's only so many people who can afford that higher cost housing, and more people can afford at the lower price. So what I'm getting at here is, if we could do that massive upzoning, where you didn't have land prices go up, you could build a lot of housing, not have value capture, and it would be consumers, buyers, renters of housing, who would mostly benefit from that; profits wouldn't really go up for developers, as far as I can tell. But the thing is, that's not almost ever how upzoning actually works. So what usually happens is you upzone just one neighborhood, or just one part of a neighborhood, or just one parcel even for an individual project. And in that case, the number of viable development sites just remains very limited. And so it's the property owners who have the market power. And so the developer, their residual land value, as we talked about, that goes up, and they're just going to pay more for the land. And so the property owner is capturing the value if you don't have any kind of value capture program in place. Whereas if you say, we're going to, you know, again, require 10, or 20% of the units be affordable, what happens there is the amount that the developer is willing to offer for the land falls back down a bit. And so instead of the property owners getting this windfall, the ones who were selling to the developers, we instead get a few affordable units out of every project. And in that context, that actually sounds better to me. You know, I would rather get a few affordable units than have a bunch of property owners get really rich from selling their properties and not having, you know, because of this windfall. So I realize that's a very long and kind of hard to follow explanation. But I'm curious of both of your thoughts on just that general concept, and like, what do we do with that?

Minjee Kim 52:49

Well, I'm thinking of... well I guess for the listeners who might not be aware of the concept of value capture, right, it's essentially this idea that certain governmental action such as upzoning increases the value property value of future development. And so some of that increment should be recaptured for the public benefit. So that's the core, you know, idea of the value capture concept. And I really do love to tell the story about South Boston waterfront, once known as the innovation district, and now it's the Seaport Square, to illustrate this case in point. So in 1970, South Boston waterfront was, you know, it was filthy; like the water was filthy, there was no transportation or transit access. So valuable waterfront land that was sitting there was sold for $5 million in 1970s. But then a series of public investments took place; the Big Dig or the Central Artery Tunnel project, which was a $14 billion public investment, which put the interstate right through South Boston waterfront and then connecting it to downtown Boston and then Logan Airport The Harbor was cleaned up, which is another, you know, several billion dollars of public investment, and then the Silver Line was put in place. So because of these series of public investment, the South Boston waterfront land that was sold for $3.5 million in 1970s, sold for and by the same property owner was sold for $200 million in 2006. So even accounting for inflation, that's a huge increase in that value, uplift. And so basically, the idea is to capture that value that's supposedly going to the landowners that were, you know, sitting on parking lot for decades to be able to use it for the public benefit. I guess I bring up this example because I think value capture is oftentimes more than just upzoning. So amenity-rich cities like Boston, and Seattle, as we know, have been growing rapidly the past decade if not longer, right? And because cities are becoming more desirable that people who are willing to pay higher rents are moving in. And that's what makes the developers pay more for a given piece of property right developable site, which again, goes back to that residual land value concept that we discussed. So if we imagine a scenario without a value capture mechanism, developers will simply theoretically bid up the land purchase price up to the point until the project is deemed feasible or infeasible. And then I think this dynamic just simply gets amplified when we're talking about upzoning but the value capture overall is much broader than upzoning, it's about cities becoming or certain places becoming more desirable, regardless of the upzoning taking place. So in those instances, again, without a value capture mechanism, the, you know, uplift will go to the landowners and some of the existing things, you know, inclusionary housing ordinances, sort of, you know, if they're functioning efficiently, in my opinion, the burden falls on the landowners that it's supposed to capture that value uplift that's going to the landowners, because again, developers will bid for less, because they can anticipate the cost of providing that, you know, whatever public amenities that they're asked to provide. But I think there's a difference between, you know, how it's supposed to function theoretically, or on paper versus how the real world functions. Inclusionary housing ordinances or other value capture mechanisms do add a layer of burden to housing developers, right, so that added logistical and administrative burden for the housing developers do, you know, have an impact on housing production, and who can, you know, get the projects, you know, through the finish line. And then also, as we well know, land markets are not perfect, right? It's one of the most imperfect markets out there. So because developers do not have all the information because the landowners do not have all the information, the idea that the majority of the burden will fall on the landowner is unclear, right? And that's where we get into whether imposing additional burden, you know, makes market-rate housing more expensive because developers are trying to cross subsidize. And, I mean, this is definitely essentially true when the land has already been paid for. So in my view, I think, value capture in theory and the value capture tools as we know, in theory, adheres to the original idea of value capture being that it's the landowners that should not profit by sitting on it without making any contribution. But the implementation of that value capture tool and the imperfect market conditions likely is doing, you know, some harm to that logic. And you know, whether or not the benefits of value capture tools outweigh the harm, or vice versa, is a question, you know, that is yet to be answered. And I guess to your point about, you know, why don't we upzone on everything, so that, you know, we can accommodate as much housing as possible, as long as there's demand for it right? I think that kind of goes back to perhaps the average cost problem, right? That you can't anticipate how much growth will happen in the future. So you create zoning regulations, and then for example, cities like Seattle and Boston, you know, become highly desirable, then you're certainly in the position to, you know, maybe completely upzone, but then we all know that the feasibility right? Political feasibility of doing that in practice is almost impossible right? So I'll just leave it at that, and perhaps Mike, you can chime in.

Shane Phillips 59:05

Mike, what do you got for us?

Mike Manville 59:07

Yeah, I mean, I think a lot of what Minjee said is correct. I guess the issues I have with the way we do value capture are largely with what the trigger is. You know, I think that the part of the problem she identified, which is this issue of well, 'the goal is to make sure landowners don't get a windfall, and we're not sure how often that happens in practice', and it becomes, in real life, a very difficult policy problem. A lot of that stems from the fact that we want to capture the value from the landowner, but we use the trigger for the policy to be development, right? And so whenever you do that, there's going to be some risk, and you can try and adjust it with different policy instruments but there's going to be some risk that the burden falls on the developer. And there's going to be some risk, I think, and this is what I think often gets overlooked, that some developments simply won't happen; not because it's infeasible totally right but just because I think the typical landowner is a satisficer, right? They're not someone who needs to make the absolute most money possible out of their property, they're someone who is fine making a comfortable amount of money at minimal effort, right? And in property markets and land markets, like Los Angeles, Seattle, Boston, and so forth, owning land is just a pretty good gig. And you can be doing almost nothing and making quite a bit of money. And so, to have someone come to you with the prospect of making more money, if you go through all the hoops that are involved in property development, you know, that end result of more money has to be really big, to change that inertia. And so that's, you know, as Shane knows very well, I'm very attached to the probably politically very difficult, if not impossible, original vision of value capture, which is just, we tax the land value and let the chips fall where they may. And I think in addition to the reason I just stated for that, the other reason, or one of the other reasons I really favor that is because there is value that comes with upzoning, you know, and it's appropriate as policymakers and planners, for us to be aware with that. But there's also just a lot of value that comes from not up zoning right? And in that, in most of our big expensive cities is the much more common situation right? And so like the South Boston waterfront, you know, grew tremendously in value as a result of public investment, and so forth, and the economy growing. You know, my parents house like quintupled in value, and they did sort of fix up the interior, they did a good job. But that's not why that happened. And it's because their suburban town really didn't build much housing for like 40 years. And so I think my fundamental hesitation with the way we approach value capture is that the not upzoning, and then not building is probably in the aggregate responsible for a lot more value uplift in a supply-constrained city, and is also more socially harmful. And so there's a certain narrative about development that arises when we make a point of trying to capture value from people who are building housing, and not from people who aren't, which reinforces what I think to go all the way back to what Minjee said, or what Shane quoted Minjee saying in her bio, which is this sort of view of development that planners have that sort of colors it with suspicion, even though in many of our cities, whether you like developers or not, we do need what they produce, which is housing. And so one of my concerns is just that it reinforces this idea that, that housing and more housing is a source of our problems, and for that reason, the people who produce it owe us something. And it's fine to say that as long as we also recognize that the people who own land, and don't build housing should owe us something as well.

Minjee Kim 1:03:16

Right, I mean, I think I mean, I've read your policy brief before joining this podcast. And I think it's a very valid sort of critique and, you know, challenge to conventional, you know, ways of thinking value capture, and I completely agree with your sort of point that it's problematic to, you know, attach value capture tools, and the trigger is that development component. That you're essentially, you know, because again the market is not perfect, and land owners , you know, they operate the way that they do that value capture oftentimes puts burden on the developers or the final end users because it's triggered when developments do happen. So we're essentially, you know, penalizing development to happen to some extent, although that might not be the original intent. So I think it's absolutely a valid, and correct critique of existing value capture practice. And I also think that, you know, you've said how value of upzoning.... there's tremendous value, but there's, you know, tremendous value of not upzoning and yes, I think that goes back to Shane's point about you know, if we can just upzone everything, there's not going to be value attached to upzoning right, so there's no more value uplift that will go to the landowners if you know, everywhere else is developable. It's because certain parts of the city, certain you know, parcels can be upzoned and can be developed is contributing to the outcome that value is being created by the upzoning. So in an ideal world, right, if we can have a zoning or regime that fluctuates and sort of responds flexibly to the changing market conditions and demand. We wouldn't necessarily have, you know, project by project, you know, value capture, you know, rationale even right. It can't be done right? But because we have a, you know, restricted and regulated land market and development sort of regime, and that this zoning cannot change and correspond to the changing market conditions, the volatility aspect that we are essentially, you know, creating this value capture tools.

Mike Manville 1:05:40